Winners and Losers: The Macroeconomic Effects of Falling Energy Prices

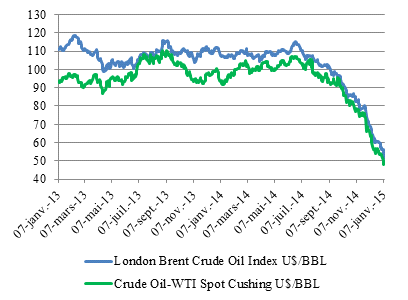

Joseph Schumpeter pointed out at the beginning of last century: the discovery and use of new raw materials can be a radical innovation likely to trigger the process of "creative destruction" specific to the capitalist system. Although North American oil is not a new resource, strictly speaking, it is one of the first examples from this century. From the exploitation of bedrock between 1,000 and 3,000 meters deep, oil and shale gas have redistributed the global energy market dynamics, with a significant and unexpected drop in oil prices since the middle of 2014 as a first consequence of this redistribution. In moving from 115 USD per barrel and 107 USD per barrel on June 19, 2014, to less than 52 USD and 49 USD per barrel on January 6, 2015, Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) have upset forecasts by the best energy markets experts.

Figure 1: Price evolution of Brent and WTI since 2013

Source: Datastream

This new situation brings up two related questions: can the price of oil settle permanently below 70 USD per barrel and, if so, who would be the winners and losers of this paradigm shift? The answer to the first question depends not only on the outlook of the global economy, but also the willingness and ability of OPEC members to stem the downward trend in oil prices. Under pressure from the other cartel members, Saudi Arabia, which represents 30% of total OPEC production, seems to accept lower prices in particular to limit the future profitability of North American deposits. By not engaging in an immediate reduction in production quantities as desired by some cartel members, Saudi Arabia is also testing the capacity of other producers to bear the financial cost of such a standstill and ultimately their willingness to commit to a sustainable reduction in their production: those who campaigned for a decline in production are, in practice, those who have the least ability to do so. These strategic interactions will determine oil prices in the coming years. However, one thing is certain: OPEC’s historic power has been eroded.

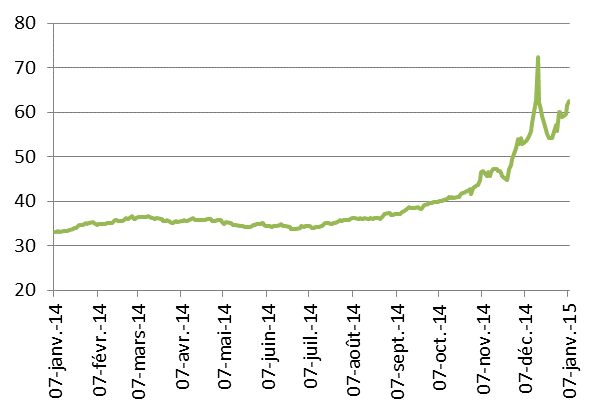

The apprehension of winners and losers in this situation, if it were to continue, calls for it to be further developed. Obviously, the main losers are and will be conventional oil and gas producing countries whose national income is highly dependent on export earnings. Among them but not limited to are Nigeria, Iran and Venezuela, respectively the sixth, eighth, and tenth largest global oil exporters in 2012, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) data. In the case of Venezuela, where oil and gas account for 95% of its export value, the drastic reduction in public spending imposed by reduced income would undoubtedly lead to substantial recessionary effects and a high social cost in an already difficult context marked by foreign exchange reserves at the lowest and rumors of payment default. The proof: the price of credit default swaps on this country’s debt skyrocketed at yearend. Nigeria, whose dependence on oil and gas is also considerable, is suffering in the same way from falling prices and promises of a strong and sustainable economic growth could be difficult to attain. Faced with the effects of sanctions from Western countries following the crisis in Ukraine, Russia, the second largest exporter, is also a loser in this new situation. The plunge of the ruble (Figure 2) reflects the economic constraints, which the country is now facing and many experts believe that Russia will enter into recession next year if the price weakness persists. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia needs the barrel to be above 90 USD, but it has sufficient financial strength to cope with a lower price.

Figure 2: Depreciation of the ruble since 2013(USD/RUB)

Source: Datastream

Producing countries of unconventional oil will also suffer from the falling prices - it is indeed a consequence of the strategic game played today - to the extent that some of the development projects become unprofitable. The closure of the most expensive fields, particularly those in the region of Alberta, Canada, and in Ohio and Louisiana in the USA cannot be excluded. However, per the IEA, only 4% of unconventional oil requires the barrel to be higher than USD 80 in order to be economically interesting. It is therefore unlikely that the price decline will lead to a short-term reduction in US production, on the contrary. Financially constrained North American producers should indeed focus on volume rather than price.

In October 2014, production from the Bakken oil field in North Dakota increased by almost 3%, while the price decline had begun. The macroeconomic situation of unconventional oil and gas producing countries is also not the same as traditional producers and counterbalancing effects are to be expected. Thus, it is estimated that if nearly 15,000 jobs were to be lost in Texas in the production sector, in the event of a recovery in US growth hiring, refining and logistics could offset these jobs.

According to Rabah Arezki, head of commodities research at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), shale gas has further strengthened the competitiveness of US manufactured goods. The decline in the prices of oil derivatives, a logical consequence of the drop in crude oil prices, should also greatly benefit the American working and middle classes, boosting their purchasing power, which is a key determinant of this country’s growth in a context of weak global demand. According to IMF forecasts, US growth stimulated by lower prices could reach 3.5% in 2015.

Oil-importing countries are of course the big winners when prices fall, although in reality the situation is more complex than it seems. For example, China inexpensively reconstitutes strategic stocks while also capitalizing on the drop in oil prices and maritime transport rates. According

to Bloomberg news agency, China National United Oil Co. bought nearly 21 million barrels from the Middle East last October. This windfall is also true for the euro area as well as Japan, heavily dependent on oil prices since Fukushima. While key rates are already the lowest in Europe, the collapse of energy prices, however,could make the implementation of a monetary policy to support growth more delicate. This could limit the most positive impacts through the threat of deflation synonymous with a sustainable decline in prices1 as they decreased by 0.2% in the euro area in December. However, economists disagree on this subject. Some see this drop as a large-scale economic stimulus, others do not perceive the spectrum of economic growth. In reality, opinions upstream differ on the precise origins of the collapse of the price levels. Fueled primarily by excess supply, falling oil prices would be a blessing for importing countries; triggered by a lack of demand, it can conversely be seen as a negative signal.

According to Rabah Arezki and Olivier Blanchard, an unanticipated decline in demand would account for 20- 35% of the decline in prices.2 Therefore it can be understood that there is no binary logic and macroeconomic recommendations determine the interpretation of the reasons

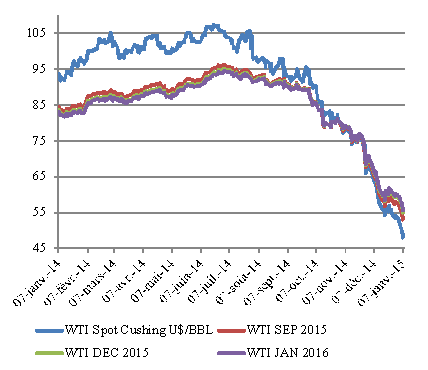

behind the falling prices. With regard to the futures structure of oil prices, a backwardation situation occurred at the beginning of 2014, and it was at contengo3 in the last quarter (Figure 3), which is a situation synonymous with remuneration for the storage activity and therefore increased demand for offshore storage, offering an indication of a possible rise in prices.

Figure 3: The evolution of the WTI market structure (spot and futures prices in USD / barrel)

From a global perspective, the net effect of lower energy prices seems positive, leading Christiane Lagarde, the IMF Managing Director, to report on December 1, 2014, that growth of 0.8% could be expected in most advanced economies. However, like any commodity, this paradigm shift cannot be appreciated only in terms of price levels, as the issue of volatility, widely discussed by economist Jeffrey Frankel, is also important. In this context, it is un-sure if the price levels will decrease, quite the contrary: the geopolitical balance and energy markets are inter-twined and both economic and political instability that could result from the fall in prices could indeed exacer-bate the volatility of financial energy markets and indi-rectly weigh on the global economy.