Will America Trigger a Global Trade War?

The new Trump administration is openly protectionist. The President called for “America First” and for “Buy American, Hire American” in his inaugural speech and his subsequent actions dispelled any remaining doubt that he meant what he said during the election campaign. As promised, he has withdrawn from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, an agreement among twelve countries across three continents that took nearly 10 years to negotiate. He has threatened American companies that invest abroad with punitive taxes and tariffs. He has signed an executive order to build a wall along the Mexican border, and he has threatened Mexico to impose a tax on its exports to the United States to pay for it. At the same time, he has ordered his team to initiate renegotiation of NAFTA, which he considers “a very bad deal”. Mr. Trump’s protectionist sentiments are not new: his many calls to refute “bad trade deals” date back to the 1980s.

Mr. Trump’s nominees also confirm his intentions. He has nominated Wilbur Ross as Secretary of Commerce, and Robert Lighthizer as US Trade Representative. They will play key roles in executing his trade agenda if, as is likely, they are confirmed by the Republican Congress. Both men have a history of advocating protection, Mr. Ross as a steel executive, and Mr. Lighthizer as a lawyer for the steel industry. The team will be supported in the White House by Peter Navarro, the author of “Death by China”, a 2010 book that advocates a boycott of Chinese goods and which has drawn high praise from the President. Mr. Navarro, an economist, heads the newly created National Trade Council, underscoring the importance Mr. Trump attaches to trade policy. Since taking the job, Mr. Navarro has pronounced the negotiations on the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership dead, and accused Germany of using the cheap Euro as an instrument to penetrate world markets.

This note will evaluate the likelihood that Mr. Trump’s policies will trigger a resurgence of protectionist policies in the United States and throughout the world. It will argue that a sharp increase in trade frictions appears inevitable. However, whether matters deteriorate into an outright 1930s style trade war depends largely on how Mr. Trump plays his hand, as well as the obstacles which stand in his way. The will and ability of America’s large trading partners to retaliate can act as a deterrent if applied judiciously and early on. National security considerations can also temper the new administration’s protectionism. Congress appears so far unwilling to support policies that blatantly disregard the United States’ international commitments. However, Mr. Trump has a number of legal instruments of protection at his disposal, and may endorse a proposal by House Republicans to enact a Border Adjustment Tax whose effects may to be just as bad as raising tariffs. All countries need to prepare for the coming trade frictions.

1. The world as seen by Mr. Trump (and what he does not see)

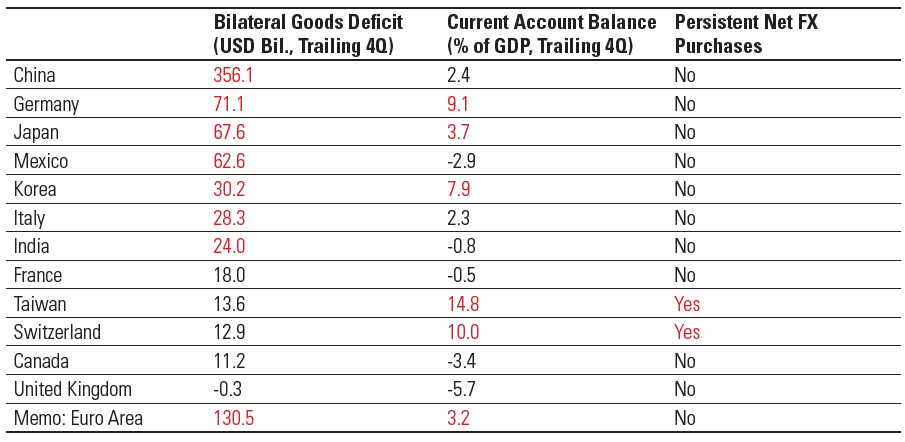

Mr. Trump is fixated on the bilateral trade deficits that the United States runs with numerous countries, which he sees not as the result of economic forces but as the result of unfair trade practices abroad and of incompetent American negotiators. A biannual report by US Treasury, mandated by Congress, is intended to identify unfair trade practices abroad. It focuses on just one aspect of unfair trade practices, currency manipulation, but it can help us understand Mr. Trump’s world view. Table 1, drawn from the latest report, lists the United States’ 12 largest trading partners. In the first column of the table below countries whose bilateral merchandise trade surplus with the United States exceeds $20 billion are highlighted in red. China runs by far the largest goods trade surplus with the United States, $356 billion in 2015. Germany, Japan and Mexico, which run bilateral surpluses greater than $ 60 billion also stand out. These are the countries Mr. Trump is most concerned with. In the rest of this article we will refer to China, Germany, Japan, and Mexico as the “Big Four”.

Table 1: Major Foreign Trading Partners Evaluation Criteria

Sources: Haver Analytics; National Authorities; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; and U.S. Department of the Treasury Staff Estimates

The merchandise trade surplus is only one of the three criteria US Treasury has adopted to identify currency manipulation, the other two being an overall current account surplus in excess of 3% of GDP (also marked in red in the second column), and systematic intervention to depress the currency. Note that though it runs a large bilateral surplus with the United States, China’s global account surplus is below the 3% Treasury benchmark and that Mexico runs a global current account deficit. Germany and Japan run global current account surpluses above 3% and so meet two of the three criteria for currency manipulation. So, none of the Big Four meet all three criteria to be identified as currency manipulators. Nor does any other country on the Treasury list. Switzerland and Taiwan are intervening to keep their currency down but their bilateral trade surplus with the United States is below the $ 20 billion benchmark. Note also that Canada, which is a NAFTA party and the United States’ largest trading partner meets none of Treasury’s currency manipulation criteria.

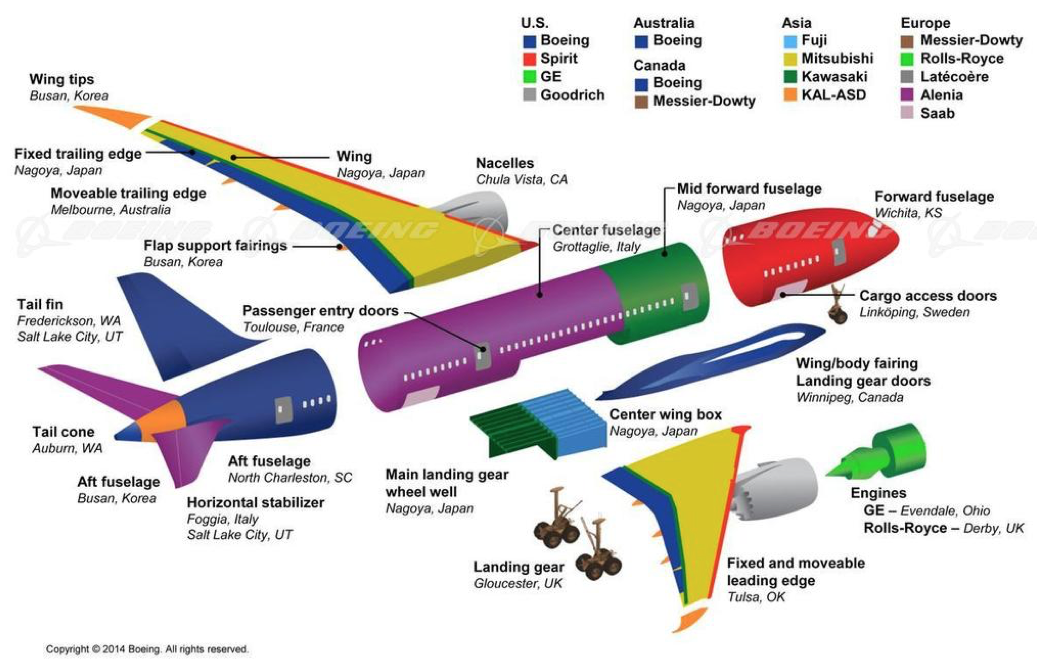

Economists know that Mr. Trump’s exclusive focus on bilateral goods trade deficits makes little sense in an integrated global economy. What matters more is the size and sustainability of global current account balances, and these depend more on domestic spending than on trade or currency policies. Without taking measures to reduce domestic spending in the United States, changes in trade policy or currency levels will have little effect on global current account balances. Moreover, about half of US imports consist of raw materials, parts and components, and raising barriers on these imports represents a tax on US production and exports (See Chart 1 on the Boeing 787 as an example)

Sources: Boeing

It is estimated that 40% of imports from Mexico consist of components produced by US companies. About 8% of the value of US exports consist of imported components that were originally produced in the US, exported and then reimported as parts of more elaborate components. This is higher than the share of the value of US exports consisting of components imported from China, which is only 7%. Various analyses have shown that China’s bilateral surplus with the US is overstated by as much as 50% because a large part of China’s exports to the United States consist of assembled products made of parts imported by China.

Mr. Trump’s premier concern is to bring jobs back to America, especially manufacturing jobs. But the US economy is near full employment anyway, and his proposed boost to infrastructure spending and tax cuts will increase demand for goods and for labor even more. In any event, the United States’ current account deficit, at 2.5% of GDP, is no longer the big worry it once was. Thanks in part to shale oil and gas such deficits are likely to be sustainable even against the background of a high dollar and faster growth than among many of the United States’ trading partners.

Taking a longer-term view, Mr. Trump’s economic nationalism makes little sense. The United States is home to less than 5% of the world’s population but has a comparative advantage in several of the largest and most dynamic global growth industries, namely ICT, aerospace, medical research, entertainment, business services, and advanced weaponry. Economists believe that advances in ICT and in automation, many originating in America, and not trade, are by far the most important source of job dislocation.

But these arguments fall on deaf ears. Mr. Trump does not see trade as a win-win proposition. He sees bilateral deficits only as proof that other countries take advantage of the United States. In the words of his inaugural addres “For many decades, we've enriched foreign industry at the expense of American industry; subsidized the armies of other countries while allowing for the very sad depletion of our military; we've defended other nation's borders while refusing to defend our own; and spent trillions of dollars overseas while America's infrastructure has fallen into disrepair and decay. We've made other countries rich while the wealth, strength, and confidence of our country has disappeared over the horizon.

One by one, the factories shuttered and left our shores, with not even a thought about the millions upon millions of American workers left behind. The wealth of our middle class has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed across the entire world.”

His belief that he can durably bring back manufacturing jobs to America runs against the established economic wisdom, but is in line with the interests of his political base, to whom he tends constantly. The core of that base – white, less educated, older workers – have seen their incomes stagnate for decades and for this they blame immigration, the outsourcing of American companies of production to Mexico and to other developing countries, the competition from cheap Chinese imports, and disadvantageous trade deals generally. This conjunction of beliefs and interests, and now power, will drive the new administration’s protectionist policies. What can stop these policies, or at least moderate their impact?

2. Moderating Influences: Retaliation, Security, Congress

There are three possible moderating influences on Mr. Trump’s trade policy: the ability and willingness of the Big Four and of America’s other trading partners to retaliate, the effect of protectionist policies on America’s alliances and on National Security, and the attitude of the Republican-dominated US Congress, which has the final say on tariffs and trade treaties. I predict (or perhaps more accurately, I hope) that these forces, considered together, will deter the President from raising tariffs in ways that are blatantly in violation of the United States’ international treaties. But the President has at his disposal various other instruments. Before we consider Mr. Trump’s protectionist policy options, we need to examine what stands in his way.

a. Retaliation

The most important deterrent to the new administration’s protectionism is likely to be the threat of retaliation by the Big Four and any other country he targets. This is, I suspect, one reason that Mr. Trump’s trade team has expressed a strong preference for bilateral negotiations, rather than for complex multilateral deals such as the Trans Pacific Partnership. If they can deal with each partner separately, the likelihood of effective retaliation is less, since as Mr. Navarro and Mr. Lighthizer have stated in different contexts, in a trade confrontation the best cards are in the hand of the country with the largest trade deficit and the biggest market, i.e. the United States. Consider each of the Big Four.

Mr. Trump has put Mexico at the front of the cue. It is seen as being in a particularly weak negotiating position, not only because of the disparity in size, but because it depends on the United States on about 80% of its exports and for some $ 25 billion of migrant remittances, a sum larger than Mexico’s oil exports.

The size disparity is much less in the case of China. However, China’s bilateral trade surplus with the United States is very large, amounting to over 3% of China’s GDP. Even accounting for the major role of imported components in China’s exports to the United States, and even if temporary, the imposition of punitive tariffs on China’s exports to the United States would be highly disruptive.

In theory, Germany – if faced with a trade confrontation with the United States – would be able to use the leverage of the wider European Union (minus exiting Britain). However, since most of Germany’s European partners, and especially France and the countries in the South of the Eurozone, have long argued that its trade surplus, now at 9% of GDP, is too big and that Germany should allow wages to rise and engage in fiscal stimulus, it is unclear how solid that support would be.

Japan is among the countries most vulnerable to US pressure. It has a chronically weak economy and has seen very large currency devaluation. It has become increasingly dependent on the United States for a security umbrella against an increasingly assertive China and against North Korea’s nuclear weapons.

In Mr. Trump’s transactional world view, the United States is in a strong position to drive a hard bargain with each of the Big Four. However, his view of trade politics is too simple. For a start, retaliation by any one trading partner may not have a big effect on the American economy, at least in the short run, but if multiple trading partners retaliate that is a different story. And retaliation by any one trading partner can cause large damage to specific industries and companies that depend on exports, even if the effect on the US economy is small. Among the export-dependent industries and companies, one could mention aircraft and engines (Boeing, General Electric), earth-moving equipment (Caterpillar), ICT (Apple and Intel), Software (Microsoft), Express Services (Fed-Ex and UPS), Construction and Oil services (Halliburton), Business Services (Google, Facebook), On-line retailers (Amazon), Health Care (Pfizer, Bristol Meyers), etc.

Higher trade barriers can have especially serious consequences on companies that operate as part of international production chains, and which need both to export and import. Among these, automobile companies stand out, with complex value chains spanning the United States, Canada and Mexico, and stretching onto Europe and Asia. Several of these companies are European and Japanese and produce in the United States. BMW, for example, claims it is the largest exporter of cars from the United states. Mexico, now a major producer of cars and car parts, may not turn out to be as vulnerable to US pressure as Mr. Trump seems to think. It is the United States’ 2nd largest export market and, according to the Department of Commerce, 1.1 million US jobs are directly dependent on exports to Mexico. The decision by Mexico’s President, Enrique Pena Nieto to cancel a state visit to Washington following an insulting tweet by Mr. Trump, and his subsequent speeches calling on Mexicans to buy Mexican products may be a taste of what is to come. The United States’ commercial interests in Mexico and in the other Big Four extend well beyond goods trade, as Table 2 illustrates. In trade disputes, the treatment of US investments abroad and of the sales of goods and services of the foreign affiliates of US companies would also be fair game.

Table 2 : US Links with Selected major economies ($ bn)

Source: US Trade Representative

There are plenty of worried people in American boardrooms, but everyone prefers to wait and see what the president will do. Large US exporters and smaller ones represented in Washington by trade associations have taken a low profile on the administration trade policy so far. Producers, retailers and oil refiners which rely heavily on imports have also been quiet. Large company CEOs are fearful of being hit by a Presidential tweet or of their companies’ being placed at a disadvantage in bidding for government contracts. They prefer their agents to engage in quiet lobbying behind the scenes. However, companies that depend on trade can be expected to step up the political pressure if they see a large and immediate risk to their operations. They would likely find allies within the Administration among the Agencies that take the lead on international economic diplomacy, of which trade is only one part. Treasury Secretary nominee Steve Mnuchin, and the head of the National Economic Council Gary Cohn, are both ex Goldman Sachs executives whose views on trade might be closer to the mainstream than those of the President.

b. National Security

The repercussions of protectionist policies extend beyond the economy and the possibility of retaliation in trade. The trading partners with which the United States runs the largest deficits are large countries, and whether their posture vis-à-vis the United States is friendly or hostile has obvious bearing on national security. The United States has FTAs with twenty nations. Although not all friendly nations have trade agreements with the United States, all of the FTAs in force are with friendly nations. Given the link between trade and national security, Mr. Trump’s debut has already caused hand-wringing among security experts. The Trans-Pacific Partnership, from which Mr. Trump has withdrawn had been motivated in large part by a desire to counter China’s growing influence. Mr. Trump’s criticism of NATO, his support for Brexit and his dim view of the EU as, in his words, “a conduit for Germany” (referring to trade) departs from 60 years of American support for the European project as a bulwark against Russia.

National security policy is made by the President, but as in trade, the President has to rely on a small number of key individuals for advice and execution. Secretary of Defense John Mathis, the Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and the National Security Advisor Mike Flynn are thought to be people with independent views and willing to speak their mind. Unlike the President, Generals Mathis and Flynn have extensive foreign policy as well as military experience. And, as the former head of Exxon Mobil Mr. Tillerson’s has had to navigate some of the world’s most turbulent political waters. Mr. Trump’s team may be more inclined than the President to take a pragmatic view on trade issues.

Take China. It is seen by many as the United States’ principal rival. Tensions over China’s claims to the South China sea and over Taiwan are never far below the surface. Yet, China needs the United States to maintain its “One China” policy (which Mr. Trump has questioned, drawing an immediate threat of retaliation from China) and the United States needs China to collaborate in dealing with just about every issue of global importance – from fighting disease, to avoiding depletion of fisheries in the high seas, to responding to balance of payments crises. Containment of North Korea’s development of nuclear delivery capability is a crucial US national security objective where China can help. Though trade frictions have been a feature of US – China relations for a long time, and are about to get worse, no one wants the relationship to break down. It is not in the United States’ security interests to see China assert its influence more aggressively, to see China promote North Korea’s adventurism, or to see the ongoing tensions between China and Japan turn into a military confrontation in which the United States would be drawn.

In the interest of security, trade disputes must not be allowed to sour the relations between the United States and Germany, allies which rely on each other for defense, intelligence, and the fight against terrorism. The same applies to Japan, which is by far the United States’ most important ally in containing Chinese influence in Asia. With tighter trade and investment ties, Mexico, which has a long history of antagonism vis-à-vis the United States has evolved into one of the United States’ most reliable allies. Collaboration with Mexico is important for national security because of its role in fighting the war against drugs, limiting illegal immigration, much of which originates in Central America and flows through Mexico, and mitigating the risk of terrorist infiltration across the 2000 thousand miles common border

c. Congress

Congress has final say over trade policy. It has more often applied the brake on trade deals, most recently on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, than it has endorsed them. However, it is one thing to stop new trade deals, another to permanently raise tariffs in violation of international treaties. The majority, not all, Democrats are trade-skeptics. At least one prominent Democrat, 2016 Presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders, has voiced his willingness to work with Mr. Trump on his trade agenda despite his total opposition to the President on other issues. However, Republicans control both the House and the Senate, and they respond to business interests which support trade deals. Together with moderate Democrats, they are likely to deploy their large majority in the House and their slim majority in the Senate to oppose an across-the-board rise in tariffs. Paul Ryan, the Speaker of the House, has ruled out a tariff increase as have several Senators. When Mr. Pena Nieto’s decided to cancel his state visit and the President ‘s spokesman intimated that the President was considering levying a 20% tariff on Mexico to pay for the wall, Congress reacted with outrage and the statement had to be quickly retracted.

Senators and House members from states and districts that depend on trade can be expected to be most active in opposing the Administration’s protectionism. Ironically, of the five States that had the largest exports per capita in 2014 (Louisiana, Washington, Texas, North Dakota and Alaska in order) only Washington did not vote for Mr. Trump. However, of the five states which are the largest exporters in absolute terms (Texas, California, Washington, New York and Illinois in order), four voted against Mr. Trump. Texas, the State with the largest exports voted for Mr. Trump, even though 37% of the exports from Texas go to Mexico. These five states are also among the states with the largest populations and the largest number of districts represented in the House of Representatives. An analysis by Brookings shows that the congressional districts that did not vote for Mr. Trump account for 64% of U.S. GDP.

While the President needs Congress to agree to a permanent increase in tariffs, the forces arrayed against a 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff hike are powerful. In 1930, the United States was in a Depression not at full employment as it is today, its trade represented barely 10% of GDP, compared to 30% currently, global value chains, foreign investment, and trade in components were in their infancy, and the United States was not bound by the WTO or by a vast network of free trade agreements. Under its WTO commitments, the United States could increase its tariffs on average by only about 1% without violating it is bindings. America’s FTAs oblige it to maintain zero tariffs on some 99% of the trade with countries party to the agreement. Enacting a high tariff would amount to unilaterally withdrawing from these agreements. Mr. Trump has been dismissive of the WTO but there are many level-headed men and women in Congress who are not. The blow to US prestige and to its ability to project power abroad that withdrawal would imply is difficult to overstate. The uncertainty such a move would generate, and the risk of retaliation would have severe repercussions on US exports, on the value of its stock of foreign investment and on the ability of American firms to operate their vast network of overseas affiliates. However, other courses of action are open to the President.

3. Mr. Trump’s Trade Policy Options

The Trump trade team clearly intends to drive a hard bargain with countries which run large trade surpluses with the United States. The list of demands on the Big Four is unknown but is potentially very long and not all of it is directly related to trade. Here are a few examples of what the United States could put on the table: China should lower its MFN tariffs, abandon its developing country status in the WTO, accelerate its reforms to promote domestic consumption, step up its efforts to protect intellectual property, and accept tight disciplines on its State-Owned Enterprises; Mexico should police its border more assiduously and agree to a renegotiation of NAFTA that entails higher (but still WTO-compliant) US tariffs and more restrictive rules of origin; Germany should undertake to increase government spending, including defense spending (buying from the United States), and promote higher wages; Japan should increase defense spending, open more of its government procurement to US firms, and reduce its agricultural protection.

Mr. Trump takes pride in his ability to strike a good bargain. That is the premise of his best-selling book “The Art of the Deal”. He starts from the view that the United States has been taken advantage of, so little may be offered in exchange for concessions by the Big Four. If the United States does not get its way, the President could deploy a vast arsenal of temporary and legal “trade defense” measures, consisting of various types of antidumping and countervailing duties. Even where their application is open to challenge in U.S. courts, or in the WTO litigation would be drawn out over several years, costly, and meanwhile the measures would remain in force (Hufbauer 2016).

Such an outcome would not represent so much a departure of measures taken in recent years, as their intensification and application to more countries and more sectors. For example, the United States has deployed numerous antidumping and countervailing duty measures against China, as have many other countries. According to estimates by Chad Brown at the peak these actions may have affected up to 8% of China’s exports to the United States - steel being the sector most often targeted. The United States has deployed other means to exert trade pressure in the past, such as “voluntary export restrictions” on Japanese cars in the 1980s (these are no longer allowed under WTO rules but depend on the injured party willingness to challenge them), exchange rate agreements to strengthen the currency of competitors (as in the Plaza Accord of 1985), monitoring mechanisms to discourage currency manipulation (such as the aforementioned Treasury report) , and monitoring of macroeconomic policies (such as the IMF’s regular reports on global imbalances), and so on.

Depending on how the negotiations with the Big Four are conducted, they could turn out to be productive or severely disruptive. Under a pessimistic scenario – which I believe is the more likely – there will be a sharp increase in protectionist measures in the United States and around the world. But it is also possible that the outcome could be reforms in the Big Four that are, on net, positive for them and supportive of increased trade with the United States and with third parties. Mr. Trump and his advisors are not entirely wrong in their belief that there are large non-tariff barriers and (in the case of China) tariff barriers standing in the way of American exporters. Nor are they entirely wrong in criticizing Germany’s mercantilism and its refusal to engage in more reflationary policies.

However, there is another big change in trade policy under consideration, which – if it comes to pass – looks like uniformly bad news.

4. The Border Adjustment Tax

The Border Adjustment Tax (BAT) is a proposal first put forward in June of last year by Republicans in the United States House of Representatives as part of a far-reaching tax reform. Republicans are now in a much stronger position to implement their tax reform agenda than they were then, and there is a considerable likelihood that the BAT will be enacted in some form as part of a new tax code.

The precise provisions of BAT are being debated, but they are widely understood to entail changing the way corporate income tax is calculated in the following way: for the purpose of calculating a company’s income tax, the cost of imported inputs will no longer be deducted from a company’s revenue; and the revenue accrued from exports will no longer be included in a company’s total revenue. This means, for example, that Wal-Mart, a large net importer, will pay a lot more tax than under the current system while Boeing, a large net exporter, would pay a lot less tax. American consumers shopping at Wal-Mart would face higher prices to offset the retailing giant’s increased tax bill and Wal Mart would have a strong incentive to buy Yogurt made in Wyoming rather than Yogurt made in Greece. Boeing, in contrast, could reduce the price of its aircraft to reflect its smaller tax bill, encouraging foreigners to buy from Boeing instead of from Airbus.

The BAT may appear arcane to many readers, but it is an important proposal supported by well-known economists such as Alan Auerbach, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, and Martin Feldstein and by House Speaker Paul Ryan. Reflecting the fact that the United States imports more than it exports, it is expected to raise about 1 trillion $ over ten years and is considered by its proponents as an essential part of the tax reform package. The revenue from BAT is needed not only to offset other tax cuts but also to fund Mr. Trump’s ambitious infrastructure investment plans. It is being sold to the new Trump administration as a way to reduce the resort to tax havens abroad and also to discourage offshoring, without raising tariffs. Peter Navarro appears inclined to endorse the BAT, and there are reports that the President, who initially found it too complicated, is warming to it.

I am not a lawyer, but it seems very likely to me that the BAT – if it turns out to include the provisions described above - would be challenged and found to be in violation of the WTO. It would be at odds with the WTO’s National Treatment principle, since imports, having crossed the US border and paid the tariff, would be discriminated against by means of the corporate income tax. If the rate on corporate income tax is set at 20%, then by not counting export revenue as part of a company’s total revenue, the United States would effectively provide a subsidy of 20% on exports. Moreover, by not counting imports as part of the cost base for income tax purposes the United States is in effect levying the equivalent of a 20%. tariff. There are ways to modify the BAT to make it less distortive of trade and so make it WTO-compatible, but not without creating major new complexities or without reducing its revenue-raising capacity (Hufbauer and Lu, 2017).

In the minds of its proponents, the BAT levels the playing field with countries that have adopted VAT (about 160 countries apply VAT, while the United States applies a Sales Tax which varies by state). VAT is viewed by them as discriminatory because it applies to imports but exempts exports. But this view is mistaken and reflects a failure to understand how VAT works. The VAT is a tax on consumption. It does not discriminate against imports, since the consumer pays the same VAT on imported products and those produced at home. And the VAT does not discriminate in favor of exports since under the VAT system, producers act merely as tax collectors. Producers are neutral on whether they sell at home or abroad. When they sell at home, they turn the proceeds of the VAT over to the government, minus the VAT they paid on their supplies, leaving them whole. When they sell abroad, there is no VAT charged to their customers but, provided they can show proof that the merchandise has been exported, they can reclaim the VAT they paid on their supplies, again leaving them whole.

It is true that a Belgian consumer buying a US product pays a much higher VAT than a US consumer pays in Sales Tax, but that is a choice entirely in the hands of the US authorities. They could raise the Sales Tax or introduce a VAT at levels similar to Belgium, raise the additional tax revenue they seek, and remain entirely WTO consistent.

Proponents of the BAT argue that it will raise revenue but it will not affect international trade because the US Dollar will appreciate to offset the effects of the tax on US trade flows. According to this view, the value of the US dollar is driven by the current account balance of the United States and if, as expected, the initial effect of the BAT will be to cause that balance to improve, the dollar will appreciate to offset its effects. But at any point in time, exchange rates respond to monetary policy, growth prospects, and asset preferences, as much as they do to the current account balance. Variations of the US dollar are only very imperfectly and variably associated with changes in the US current account balance. As already stated above, current account balances respond to changes in domestic demand more than to changes in tax and tariff policies. For example, over the last two years the US Dollar appreciated some 15% in trade-weighted terms, yet neither US tax policy nor US tariff policies changed. Thus, there is no reason to presume that currency movement will exactly offset the effects of the BAT.

But the more important objection to the notion that currency shifts will offset the BAT relates to the ability of the WTO to discipline trade policy. If the principle of a BAT as currently configured became accepted, then any tax measure discriminating against imports and any subsidy of exports could be justified on grounds that the currency will adjust. The United States is the world's largest economy and the architect of the WTO. The introduction of BAT – if configured as currently understood – is not only likely to be challenged in the WTO but if the United States persists with it, could sooner or later undermine the system.

5. How should other countries respond?

Introduction of the BAT would be bad for everyone: the United States, all its trading partners, and, very likely, for the WTO. Therefore, it is essential that America’s trading partners, large and small, deploy their diplomacy and advocacy to argue against the proposal as it stands. They must dispel the notion that they will accept the BAT as WTO compliant. They should also not hesitate to declare their intention to stage a WTO challenge, and to retaliate according to WTO norms if , as I expect, the WTO appellate body finds against the BAT. WTO disputes take many years to resolve, but, meanwhile, counter-vailing duties, which can be applied rapidly, may serve as an adequate deterrent.

The Big Four will each have to examine their options in the face of the coming challenge to their policies by the United States. They should be prepared to concede ground on the market opening measures that the United States will call for, and consider what space there is on the macroeconomic front to boost their economy. EU members should step up their pressure on Germany and on other European surplus countries to do more to stimulate their domestic demand. But the Big Four (and the EU which conducts trade negotiations on Germany’s and its other members’ behalf) should also not hesitate to place their own reasonable trade demands on the United States and to resist any backtracking on the part of the United States on its own liberalization. Their domestic politics will demand no less. If necessary, they should be prepared to retaliate if the United States resorts unreasonably to antidumping and countervailing duty actions, violates the government procurement agreement of which it is a signatory and if Mr. Trump persists in his “Buy American” rhetoric.

Mexico faces a special challenge as it renegotiates NAFTA. Its negotiating position is not as weak as many seem to think. Mexico is a large export market for the United States. Without leaving the WTO, a drastic step, the United States cannot raise its tariffs on Mexico above its very low WTO bindings while Mexico’s WTO tariff binding are moderately high. The United States needs Mexico’s help to patrol its border.

The majority of America’s trading partners are currently off Mr. Trump’s radar screen. They may see his determination to reduce bilateral trade deficits with the Big Four as an opportunity to gain share in US markets and to export more to the United States. This expectation is not entirely unfounded, since with US aggregate demand likely to be boosted by tax cuts and infrastructure spending, and the dollar may appreciate further making selling into the U.S. more profitable. Under this scenario, America’s global current account deficit is more likely to increase than decline even if the bilateral deficit with the Big Four shrinks. If the United States prevails on Germany and China to do more to boost their domestic demand that may also help third countries.

However, this sanguine view must be tempered by two considerations: In the short-term, Mr. Trump’s policies may cause US interest rates to rise even faster, diverting capital flows towards the United States. Countries with large debts denominated in US dollars will suffer, especially if the BAT is enacted. In the long-run, Mr. Trump’s aggressive protectionism may usher in an era of escalating trade frictions that encourages country after country to turn inwards. In that scenario, everybody loses.

An unintended effect of Mr. Trump’s abandonment of TPP and his trade policies generally will be to encourage both small and large countries to consolidate their bilateral relationship with the other large trading nations and blocks, namely China, the EU, Japan and Russia, as well as to pursue trade deals at the regional level, probably giving a boost to the interest in RCEP, ASEAN, GAFTA, the Pacific Alliance, to name the most important.

Conclusion

This paper has argued that a sharp increase in trade frictions appears inevitable, especially between the United States and the Big Four countries with which it runs large trade deficits, China, Germany, Mexico and Japan. The will and ability of America’s large trading partners to retaliate can act as the most important deterrent to Mr. Trump’s protectionism if applied judiciously and early on. National security considerations are also likely to temper the new administration’s trade policies. Although Congress appears so far disinclined to enact increased tariffs, a policy that would violate the United States’ international commitments, Mr. Trump has plenty of legal instruments of protection at his disposal, including antidumping and countervailing duties. The renegotiation of NAFTA also offers opportunities to legally raise new barriers against Mexico. Unless deterred early on, it is quite possible that Congress will enact some version of a Border Adjustment Tax whose effects may just as bad as raising tariffs. Much depends on the United States’ largest trading partners making their voices heard early on, and on their leaving no doubt that they will retaliate within their available legal means if their trade interests are given short shrift.