Economic integration in the time of turmoil

Integration into the global economy is essential for rapid and sustained growth, but the countries of the MENA region remain among the least integrated, and were so even before the Arab uprising and the spreading turmoil. To fight poverty and create jobs, the MENA countries must engage in a broad-ranging process of reforms designed to enhance their competitiveness. Trade agreements can provide an important supporting role to this effort, but only if they are part of a wider process of domestic reforms and they are truly ambitious in scope.

The weak trade performance of the MENA region has been extensively documented and analyzed. Beginning in the early 1990’s, the writer has worked at irregular intervals on some 7 or 8 separate examinations of the economic integration of the MENA region and of individual countries in the region, and it is frankly distressing how little the story on trade has changed.

There is no doubt that a truly ambitious trade initiative – part of a broad country-driven reform effort designed to improve the business environment and boost productivity – and supported by the region’s main trading partners through enhanced market access and funds - would boost the region’s development prospects. Such a trade initiative, one that could conceivably be comparable in scope and ambition to that which propelled the EU’s accession countries, would also lead to accelerated integration within the region, bind the region more closely with its European neighbors and the United States, create jobs and help reestablish the region’s badly frayed social contract.

Yet, with open conflicts in Libya, Syria, Iraq and Yemen raging, the anarchy threatened by ISIS, tensions between Iran and the Gulf countries prevalent, widespread political repression in Egypt, and millions of people displaced, the sad fact is that the political and security pre-conditions for such an initiative are today absent in large parts of the region. With some exceptions, such as Morocco, a country that has shown relative stability and is currently (with much hesitation and resistance) negotiating a deep and comprehensive FTA with the EU, and, moreover, will derive great benefits from lower oil prices, or Tunisia where the process of democratization is most advanced, the MENA countries are too beset by rifts to place a high priority on trade reforms. Indeed, while these reforms are badly needed, where there is no security and any prospect of stability, trade liberalization is more likely to destroy jobs than to generate new investments in export industries. At the same time, as long experience has shown, stability that is perceived as fleeting, or is imposed by rent-seeking elites, will also stifle economic progress. Renewed stability that is built on pluralism and the popular voice is more likely to last and to shift the political economy in favor of reforms that favor the whole population.

But even were the countries of the MENA region ready, the advanced countries appear unprepared and unwilling to embark on major new trade initiatives and to provide increased financial support. In the wake of the great financial crisis, the EU and the United States are too preoccupied with their own internal divisions, over-stretched budgets, and by immediate threats to their security and their prosperity such as Ukraine and Greece. The enormous costs and dismal result of military interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya remain fresh in everyone’s minds and, together with the sheer unpredictability of where the next flare up will be, contribute to the climate of caution.

Though it is generally assumed that the advanced countries should extend their help to the MENA region as it struggles with major political upheaval, the fact is that, since the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007-2008 incomes per capita in the US and Europe have advanced at a slower rate than in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia (countries in transition which I refer to as CTs for short). Moreover, the youth unemployment challenge in Spain, Italy and Greece is no less daunting than that in the CTs, and public debt as a share of GDP has risen about three times faster in the advanced countries than in the CTs. In addition, governments in the US and EU are currently devoting their precious political capital to the high profile and enormously complex negotiations of TTIP and TPP. No surprise, then, that the flow of trade agreements in the region has ground to a halt: the last EU-Med Association Agreement was with Algeria in 2005, and has been largely inconsequential.

Yet, it is wrong to paint the picture as uniformly dark. The advanced countries are well set on a course of recovery, and, in a remarkable demonstration of resilience, the MENA region’s average per capita income has continued to rise in recent years and is predicted to increase at 1-2% a year in 2015 and 2016 despite the turmoil. Amidst the conflicts, monarchic regimes have shown continuity in the Gulf countries, Morocco and Jordan, and a democratic transition is being effected in Tunisia. With all their vulnerabilities and shortcomings, the economies of Jordan, Lebanon and Algeria continue to function.

It is important even in the midst of turmoil to recognize the region’s poles of relative stability and to build on them. This note seeks to articulate some principles that can help guide the ongoing search for long-term solutions to the region’s growth and integration problem, including through trade agreements and other forms of external support. We begin by reviewing briefly the record of the CT’s trade performance and the effect on them of trade agreements, focusing mainly on those with the European Union, which is still the CT’s most important trading partner.

The trade record

Though the region has seen increased integration with the rest of the world through trade and foreign investment, and integration has contributed to the region’s growth, outcomes have been disappointing in comparison to the most successful developing regions and, more importantly, have fallen short of those needed to provide the region’s burgeoning young population with good jobs.

Research shows that oil importers and the MENA region more broadly could be engaging in significantly more trade, both within and outside the region. For example, using gravity models, which predict countries’ trade flows as a function of their economic size and distance, Ferragina et. al (2005) conclude that the volume of trade between the European Union (EU) and the MENA countries could be 3.5 to 4 times larger than it currently is if the two regions were to reach the EU’s level of integration. Intra-regional trade within MENA is also low relative to that predicted by gravity models and worse than that in sub-Saharan Africa. The latter finding has been recently challenged by Freund and Jaud (2015) who find that countries in the region may be over-trading with each other, in part because they under-trade with the EU.

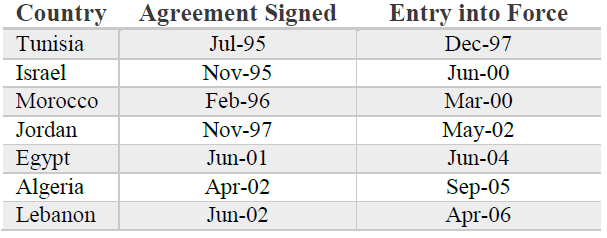

Moreover the trade agreements of Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia with the EU, have by and large failed to deliver on their promise. Though these agreements form part of a broader Mediterranean initiative to foster the region’s integration (see table), they are widely recognized to be low-ambition, partial deals, which fail to address some of the region’s main impediments to successful integration.

Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreements

An examination of the CT’s trade performance to 2007, preceding the global financial crisis and the Arab uprisings which made the trade picture very murky, shows that, after their respective association agreements with the EU came into force their exports to the EU accelerated only marginally (with the exception of Morocco’s). Moreover, over 1997-2007, CTs exports to the EU increased slightly less rapidly than to the rest of the world. CT’s total exports and (especially) total imports also grew less rapidly than the developing country average. Moreover, Europe’s Eastern partners—the largest recently-acceded EU countries (“accession countries”), the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary; and those that have not acceded (“non- accession countries”) and have no free trade agreement with the EU, Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine —outpaced its Mediterranean partners in export growth over 1997-2007, by a wide margin. Furthermore, minerals, fuels, and lubricants accounted for the lion’s share of CT export growth over the relevant period, mainly resulting from higher prices for Egypt’s large exports of these products. In more recent years – 2007-2014 – there has been a deterioration in the export performance of CTs relative to the rest of the world and relative to the accession countries.

Although foreign direct investment (FDI) in the CT’s increased significantly and grew more rapidly than that in most developing regions, they attracted much less FDI —both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP—than the EU accession economies. Over 1997 to 2007, FDI inflows to the MPs grew handsomely by over 40 percent on average annually and amounted to about $73 billion. However, over the same period FDI inflows to accession countries were more than 4 times that size and accounted for 6.7 percent of GDP—twice the GDP share of the MPs. Not surprisingly, in recent years, FDI has largely shunned the countries most affected by the uprisings.

In the CTs, significant FDI goes to tourism (a large, labor intensive export sector), but, beyond that, FDI is disproportionally oriented toward the natural resources sector and toward supplying the domestic markets. In addition to tourism, FDI in the region has mostly been directed towards construction, energy, telecom, and associated services. Little FDI goes to manufacturing. As a result, in contrast to the accession countries, where intra-regional trade has grown as multinational production networks have taken hold, FDI appears to have played a very limited role in spurring trade among the CTs and their surrounding region.

Why have the results from trade agreements been so disappointing? Prior to the current set of EU-Med trade agreements, the CTs already had largely free access to European markets in manufactures—which account for the lion’s share of their trade—and they also enjoyed a small margin of preference vis-à-vis most other large exporters under GSP arrangements. Therefore, the impact of the agreements on CT exports to the EU was naturally small. In fact, the agreements’ big trade liberalization measures were all on the CTs’ side.

Moreover, a variety of impediments—including subsidies, quotas, reference prices, and seasonal barriers—continue to hobble exports in the areas where the CTs have a clear comparative advantage, notably agriculture, while a schedule for moving toward free trade was set for manufacturing, in which the EU has a comparative advantage. According to the OECD, EU support to farmers accounted for 24 percent of gross farm receipts and around 50 percent of value added, on average, annually over 2007-2009. For the CTs, access to the EU is especially important in goods such as fruits, vegetables, and vegetable oil. The CT agricultural sector supports a significant part of GDP and an even larger share of employment. For example, in 2009, agriculture accounted for 14 percent of value-added in Egypt and 16 percent in Morocco. In addition, it accounted for 31 percent and 41 percent of employment in the two countries, respectively.

Restrictive rules of origin and limited cumulation further restrict the CT’s effective market access to the EU. Diagonal cumulation exists across only a subset of countries and ROOs differ across some Euro-Med countries. The ROOs for Egypt are not the same as those for Tunisia and Morocco, for example. Adherence to specific and complex ROOs places a burden on exporters who may not be familiar with the specific rules and requirements. Studies suggest that the presence of restrictive ROOs account for the failure to utilize preferences. For example, over 1996-2006, as much as 18 percent of Jordan’s exports to the EU that should have been duty-free paid duties, possibly because of the high costs of obtaining certificates of origin. If properly applied, the new Pan-European-Mediterranean ROO system, introduced in 2011, could help remedy some of these problems.

Another major shortcoming of the current EU-CT agreements is related to the movement of workers. The EU-CT association agreements essentially reaffirm both groups’ very general obligations under the WTO GATS, making no commitments on the number of skilled (or unskilled) workers allowed to work temporarily in the EU. The agreements with Morocco and Tunisia include commitments on non-discrimination with respect to working conditions and social security for their nationals legally working in the EU. Those with Algeria and Jordan contain somewhat more liberal provisions, including limited movement of intra-corporate transferees or key personnel within one organization.

The aid flows associated with the EU trade agreements with the CTs are tiny compared to the needs and to what became available to accession countries, as are the mutual reform commitments. For example, the Czech accession agreements provides for incorporation into the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy—giving Czech producers subsidies comparable to farmers in existing members, and making agricultural exports into the EU free but conditioning production by a system of quotas or by various reference prices; allocation of structural funds amounting to €26.7 billion (18 percent of 2010 GDP) over 2007-2013: adoption of the EU rule book (acquis communotaire) in behind-the-border reforms and more, including the adoption of community-wide standards; adoption of the much lower EU common external tariff; formally unrestricted access to service producers, though access remains constrained by a host of domestic regulations; freedom of investment and general movement of capital; and, last but not least, the free movement of people.

It is also worth noting that US agreements are more far-reaching than EU agreements. For example, the U.S.-Morocco FTA covers all agricultural products and the United States has committed to phase out all agricultural tariffs; though schedules differ by product, all tariffs will be phased out over fifteen years.

Intra-regional trade has, overall, performed worse relative to benchmarks than extra-regional trade. Non-tariff barriers remain big obstacles. Most tariffs in the region have been removed under the two major preferential agreements in the region─ the Pan Arab Free Trade Area (PAFTA), which came into force in 1998 and allowed duty free access to its 17 member countries’ markets; and the Agadir agreement, between four countries, which came into force in 2007. Nevertheless, red tape, poor logistics, lack of transparency, and complicated customs clearance hamper regional trade. For example, the region’s exporters occasionally have to obtain special import permits to avail themselves of preferences that should be automatic under trade agreements.

Principles Underlying Future Action on the Trade Front

Charting an economic strategy for the region at present is like driving through a very thick fog. However, this brief examination of the historical record and common sense suggest that any realistic strategy must be based on four principles:

Predictability: There can be no growth and no successful economic integration without international competitiveness and willingness to invest, and, first and foremost, investors look for rule of law, security, stability – in a word, predictability. And this means that the long-term investor, whether foreign or domestic, wants also to be convinced that today’s stability is not fleeting but rooted in sufficient political consensus, even if it falls short of democratic ideals. Reestablishing predictability should be job 1 of the region’s policy-makers. The US and EU, on their part, must accept that the political regime is to a large extent a given – it can be externally disrupted but it cannot be externally imposed. To fulfill their poverty-fighting mission and promote international integration, development agencies such as the EU directorates involved in outreach to partners, USAid, JAICA, DFID, etc. and the World Bank must identify the region’s poles of stability and build on and around them. In a role that is familiar to them, they must step up their work with civil society and the authorities to strengthen the effectiveness and legitimacy of the state, and they must help ensure that today’s refugees do not become tomorrow’s insurgents. Going beyond their traditional mandate, they must also find ways of building bridges among opponents that reduce the likelihood of conflict.

Autonomous Reforms. As the historical record amply illustrates, predictability and stability are necessary but not sufficient to promote international integration. Perhaps the most important policy message is that successful international integration cannot be driven externally – it can only be achieved if it is driven by a wide-ranging process of domestic reforms designed to enhance the nation’s productivity and competitiveness. At the heart of these reforms are what I call the four C’s – Connectivity with the world, which includes opening the trade regime and good logistics and communications, Capacity, which includes investing in skills, Cost, which includes maintaining a realistic exchange rate and effective regulations, and Confidence, which includes the rule of law and sound macroeconomic policies.

Ambition. Trade agreements can provide a secondary but important supporting role to the domestic reform process, provided they are ambitious in scope. Trade agreements that only make changes at the margin achieve little directly by definition and they also provide no political leverage for the reform-minded to push the development agenda. Trade agreements must therefore address the real barriers to integration facing the MENA region – agriculture subsidies and tariffs, enforceability of provisions against non-tariff barriers, restrictive rules of origin, draconian restraints to labor mobility, financing of transport infrastructure and of modernization of customs, and so on. The largely successful EU treaties of accession go well beyond what can be envisaged for the MENA countries in the political dimension, but they also show what is possible in the economic sphere– including, for example, the benefits of a customs union, the free movement of capital and labor, and of real disciplines to drive institutional reform, as well as the importance of structural funds which can amount to 3-4% of GDP a year.

Global Reach. The EU’s geographic proximity and historical and economic ties to the Arab world give it a special role in the region, and the United States has a long-standing interest in the region’s security and its energy resources. However, the interests of other oil importers, such as Japan, China, and India also loom large and those of China – the world’s largest exporter- have been advancing at a very rapid pace. The Gulf countries also have a vital stake in the stability of their Arab neighbors. In developing aa joint strategy to foster the region’s peace and prosperity, the EU and US should reach out to China, recognizing that it is likely to become the region’s single most important trading partner in the not distant future. They should work closely with a multilateral lender such as the World Bank, which is especially well-positioned to greatly expand the coalition of actors interested in fostering the region’s integration, especially

The conditions may not be ripe today to launch a major regional trade initiative in MENA, but work along the lines of these four principles should begin now, especially on measures designed to enhance predictability and stability. As the world economy continues to recover from a disastrous crisis, and the popular demand for reforms from within the region intensifies, and – hopefully – as some of the region’s long-standing conflicts are resolved or at least mitigated, opportunities will arise for genuine progress in individual countries if not across the whole region. Reformers in the MENA region and the international development community must be prepared to seize those opportunities.