Africa and global commodity markets: from cyclical realities to structural

In June 2017, the second Annual Report on Commodity Analytics and Dynamics In Africa (Arcadia report) was published, in collaboration between the OCP Policy Center and CyclOpe. Its aim is to annually report on the evolution of the economic, legal, financial and societal links between Africa and the world commodity markets, both with regard to the cyclical changes in the markets, and to the structural changes or failures that may have emerged. Focusing on 2016 and early 2017, the Arcadia 2017 report analyzes the rebound in commodity prices, particularly mineral prices, which are important for the African continent. In a still difficult macroeconomic context characterized by weak world trade and (geo)political uncertainty, the recovery offered needed relief to the continent's producing countries. However, it did not allow them to significantly improve their public finances. While 2017 should be under better auspices, African countries’ commitment to addressing the many structural challenges that condition their economic and social development does not appear to have weakened. The Arcadia 2017 report focuses on a full accounting of the central issue of food security to the electrification of the continent, from the financing of African states to the reform of mining codes and agreements.

Contrasting cyclical realities

2016 and early 2017 were characterized by very moderate global economic growth, penalized by sluggish world trade and a structural weakness in private investment. In the commodities sector, however, a significant rebound was observed in prices following the 2014 and 2015 collapse.

A slight improvement in the commodities sector

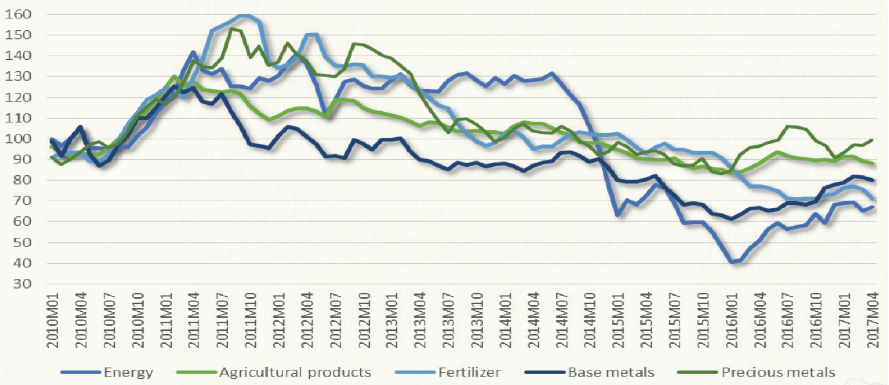

While commodities have evolved in a scattered manner during 2016 and the first few months of 2017, it should be noted that overall market conditions have improved compared to the catastrophic situation of previous years. Thus, according to the World Bank's monthly statistics, energy prices (coal, crude oil and natural gas) rose by almost 69% in 2016, while base metal prices (copper, aluminum, tin, nickel) increased by 27% overall. Precious metal prices (gold, silver, platinoids), on the other hand, rose modestly by just over 7% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Monthly change in commodities prices (2010-2017, base 100 index in 2010)

Source: The pink sheet, World Bank

Present in the African subsoil, iron ore, whose price has jumped by more than 70%, and cobalt, which literally soared at the end of 2016 and the first half of 2017 due to bullish speculative movements, are both among the big winners in 2016. This has clearly been good news for African producer countries, whose economic growth and public finances have been hit hard by the 2014 and 2015 market collapse. The high levels reached in 2010 after the major setback fueled by the 2008 financial crisis are, indeed, still very far off.

Figure 2: Price change in African-origin metals

Source: Quandl.com

Agricultural products, on the other hand, overall have not enjoyed the same fortune: behind the 7% increase in the World Bank's agricultural price index, there is a considerable heterogeneity. In particular, cocoa prices fell after the peaks reached in 2015. During the 2016 calendar year, the ton of beans lost 22% of its value on the London Stock Exchange and 34% in New York, which had an impact on the economies of Ivory Coast and Ghana, the world's largest and second largest cocoa producers, respectively. The world cereal production from the 2015-2016 and 2016-2017 seasons were characterized by low prices. The price of American soft wheat (soft red winter –US SRW) dropped from an average value of $191.70 per metric ton (MT) in January 2016 to $161.10/MT in December 2016, while corn fell to $152.44/MT at the end of 2016 compared to $161 in the previous January. As a point of reference, the US SRW and corn were at $215.60 and $178.70/MT respectively in December 2014. In this context of global abundance of grain, Africa experienced two successive years of poor harvests in 2015-2016 and 2016-2017, in different regions. This is due to a severe drought in the northern part of the continent in 2015, and in the east in 2016. For coffee on the other hand, however, the composite index of the International Coffee Organization (ICO) went from 155.26 cents (cts) per pound (lb) in 2014, to 124.67 cts / lb in 2015, to reach 127.31 cts / lb in 2016. Cotton prices also rose during 2016 and early 2017. The Cotlook index, which quotes a variety of cotton from various origins (including Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Mali, Tanzania, Chad, Zambia and Zimbabwe) based on cost insurance freight (CIF), noted that Far East rose from 151.56 cts/kg in January 2016 to 175.26 cts/kg in December 2016, which is an increase of over 15% during the year (World Bank).

Macroeconomic heterogeneity persisted in 2016

The relative price improvement observed for most commodities took place within a very dull macroeconomic context. Global growth has been at 3%, and 2017 is not expected to significantly change this reality even though positive signals could be identified during the last months in 2016. Penalized by the dollar’s strength and by the decline in oil prices, US economic growth was only 1.6% in 2016. In economic terms, however, everything was not disappointing. Two and a half million jobs were created in the market economy, bringing the country's unemployment level below 5% and, for the first time since the 2008 crisis, bringing down tension in the job market as well; A situation that can be linked to the decision to raise the US Federal Bank Reserve (Fed) key rates. China, for its part, managed to keep its economic growth above 6.5%, and achieved this thanks to public investment and an accommodative monetary policy. Thus, while the central question of the impact of the transformation of China’s economy remains unanswered, it must be acknowledged that China has, from this standpoint, provided reassurance. The argument is not only a macroeconomic one, in light of Donald Trump’s protectionism and the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris climate agreements, Xi JinPin has affirmed himself as both a free trade advocate and a guarantor of his country's environmental commitments. However, these affirmations cannot discount the reality of the Chinese steel and aluminum sectors nor the consequent existence of trade disputes between China and the rest of the world in this area.

Strong heterogeneities have naturally been observed throughout the world, and the African continent has not escaped this reality. According to the latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) statistics, real GDP growth in Sub-Saharan Africa stood at 1.4% in 2016, far from previous years’ performance (Table 1).

Table 1: Economic growth in Africa (In real GDP growth rate)

Source: Regional economic perspectives, IMF

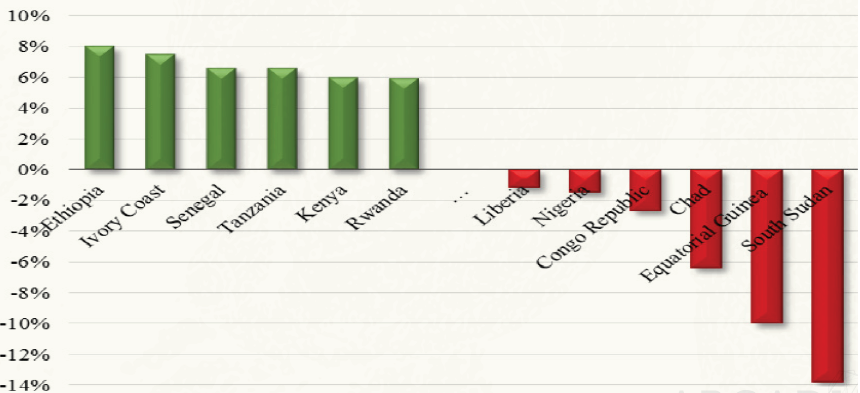

Behind this general number are hidden very different macroeconomic performances with, on the one hand, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal and Tanzania, whose economic growth has equaled or surpassed 6%, and on the other hand Equatorial Guinea or South Sudan, whose economic activity has fallen sharply (Figure 2). Unsurprisingly, African countries exporting non-renewable resources, especially oil, have suffered the most from a macroeconomic perspective. On average, their growth has been halved and the relevance of their macroeconomic management has been undermined by rising imbalances and indebtedness. Moreover, these exporting economies have very often experienced a weakening of their currency resulting in rising inflation and greater difficulties in capturing external financing.

Figure 3: Macroeconomic performance of selected African countries in 2016 (real GDP growth rate)

Source: Regional economic perspectives, IMF

The continent's three main economic drivers, Nigeria, South Africa and Angola, were particularly lackluster in 2016. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2017) statistics, the Nigerian economy entered into recession and contracted by 1.5% for the first time in two decades. The South African economy recorded its weakest growth since 2009 at 0.3%, while that of Angola was zero in 2016. In Nigeria, the drop in oil prices, on which the economy is 70% dependent on, led to a negative external current balance in 2015 (-3.2% of GDP) for the first time in a decade (0.6% in 2016). The budget deficit decreased to -4.4% of GDP in 2016 (-3.5% in 2015), despite adjustments to current expenditure. Angola, on the other hand, responded more quickly to falling prices by revising the 2016 budget in July to limit public spending, which amounted to 23.7% of GDP in 2016. Public debt has nevertheless more than doubled since 2013, representing almost 71.9% of GDP in 2016. The current account has improved considerably but remains negative at -4.3% of GDP. South Africa also experienced difficult years in 2015 and 2016 due not only to the low price of gemstones, minerals and metals, while they comprise about 50% of the country's exports, but also from external demand, particularly from China. In addition, strikes and the decline in the competitiveness of the mining industry, a (still) difficult supply of electricity, anemic household consumption, and droughts have contributed to low growth of national income. On the other hand, inflation is still high, with a logical depreciation of the rand as a backdrop. A tense political climate compounded this difficult situation.

2017 is expected to offer a slightly more favorable macroeconomic outlook for the African continent, due in particular to the improvement in the price of commodities. However, this is insufficient for significant improvement of the public accounts of countries that would not change their fiscal policy accordingly. The stakes are high because the gradual normalization of US monetary policy following renewed inflation could weigh on the external financing of the African continent and thus constrain its economic rebalancing. The increase in the Fed's key rates naturally raises the question of its impacts on the US economy as well as on the conditions for granting international financing.

2016: a year of (geo)politics

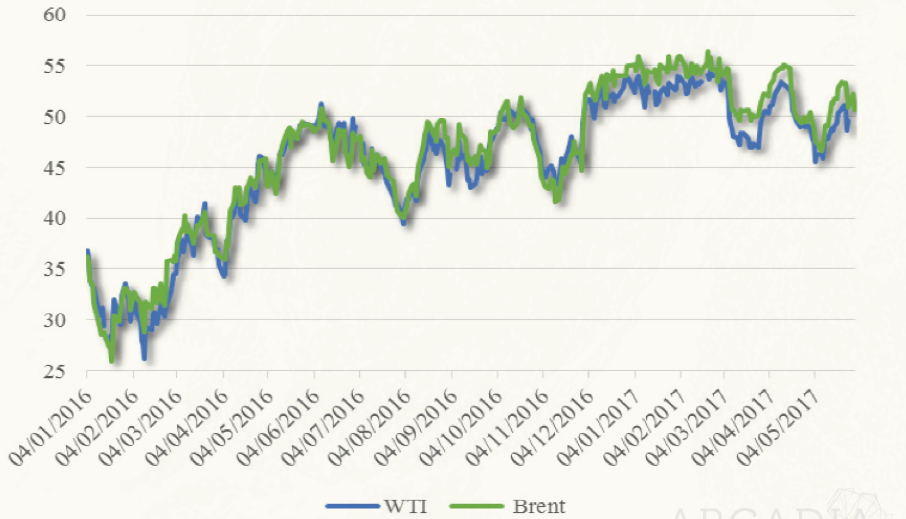

A macroeconomic approach is insufficient for conducting a cyclical analysis of the links between Africa and the world commodity markets. From the surprise election of Donald Trump as President of the United States to the European Brexit earthquake, whose outcome is even more uncertain since the British parliamentary elections in June 2017, many major political events have taken place in 2016, let alone the global geopolitical developments particularly in the Middle East. Within the commodities sector, the most visible event in 2016 was probably the agreement reached by members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in December to reduce production of 1.8 million barrels per day (mb / d), thus encouraging price recovery. There was urgency since Brent, the reference for crude oil, had begun in 2016 at levels below $38/bbl and then dropped further during the first weeks of the year to reach a floor price of $28.70/bbl on January 20, 2016. It subsequently picked up a bullish path despite significant downward movements. On November 30, 2016, by endorsing the tentative agreement reached in September, OPEC allowed oil to average $55/bbl above average levels between mid-December 2016 and mid-March 2017. While oil inventories have declined, the upsurge in US non-conventional oil production, fueled by this price increase, once again pushed crude below the $50 threshold at the beginning of May 2017. Not surprisingly, on May 25, 2017 OPEC decided to renew this agreement until March 2018.

Figure 4: Change in oil prices (2016-2017, FOB spot price, in USD/bbl)

Source: US Energy Information Agency (IEA)

West African crude prices have logically followed the general market trend with a significant increase in prices since November as a result of this OPEC agreement. Nevertheless, the increases were lower for Nigeria (Cabinda) than for Angola (Girassol). Two key factors explain this differentiation, which are, first, the abundance of light crudes in world markets due to US production and the uncertainties surrounding oil exports from Nigeria (that were penalized by the attacks by various armed groups against oil installations) and second, infrastructures in the Niger Delta region.

While oil obviously occupies a key role in the international economic and political scene, it must be noted that political decisions have driven the large minerals and metals sector - this time the impetus is related to consumer and/or importing countries instead of the producer countries. There is, thus, little doubt that the American and Chinese political authorities have buoyed a number of raw materials produced by African countries. As a candidate, Trump promised to spend billions of dollars on infrastructure projects and, speculatively the price of copper increased by over 28% between October 24 and November 28 to reach $5,935, its highest level in a 21-month period. The same observation applies to China where billions of yuan were injected into infrastructure projects, while the persistence of cheap credit and the lifting of rules restricting real estate transactions have boosted real estate investments and indirectly supported many industrial sectors. These measures are favorable to steel and aluminum in particular, and have in turn benefited iron ore and bauxite, of which South Africa and Guinea are respectively major producers on the continent. Guinea, the leading African bauxite producer and holder of over a quarter of the world's ore reserves, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), enjoyed a very favorable year in 2016 with exports to China up sharply. It must be noted, however, that export restrictions on unprocessed ore by Indonesia and later by Malaysia have less impacted international competition.

Structural challenges to be overcome

An analysis of commodity market conditions cannot, of course, fully account for the links between Africa and the renewable and non-renewable resources that it produces and exports. The Arcadia 2017 report therefore focuses on analyzing the major challenges facing the continent, such as improving the attractiveness of extractive industries (especially mining), promoting electricity generation capacity through renewable energies (i.e. solar, hydroelectric), enhancing food security and promoting a specific model of agricultural development, and enhancing the capacity of nations and businesses to raise funds efficiently, in particular on international markets, in the form of both debt and equity.

Improving the attractiveness of the African extractive sector

Africa has considerable mineral resources but has relatively low exploratory investments per km2 compared to other mining regions such as those found in Australia or Canada. It is therefore legitimate that the socio-economic development of this exceptional geological heritage is among the priorities of the countries in question. Since their independence, African countries with mineral resources have adopted foreign investment laws and have developed mining and oil codes. The particular characteristic of each extractive project has, moreover, led to the completion of these codes through agreements signed between the State and the private operator in order to reconcile the interests of the State, the investor, and the local populations while taking into account the economic realities and infrastructures available or to be built. Given the legal complexity of this effort and the importance of the strategic issues that the extractive sector implies, many African States have also joined forces to develop standards applicable at regional and international level. This was the case for the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) in 2003 and for the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 2009 and 2012.

The most recent reforms of the national codes for mining activities contain many common principles inspired by these various regional initiatives, which generally aim to increase the direct and indirect profits of States. The general idea of these codes is to adopt a less liberal approach and to strive for a better redistribution of wealth, in particular by increasing state capital participation, revising tax exemptions or increasing taxes. The year 2016 was marked by numerous reforms in the extractive sector: in the DRC, Gabon, Ghana, Rwanda and Congo-Brazzaville for the hydrocarbon sector; and Djibouti, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Cameroon and Morocco for the mining sector. In the course of 2016, discussions were also held between the various stakeholders on draft mining codes in Zambia, Madagascar, the Republic of Congo and the DRC. Despite the singularities of some of these reforms and the divergences in the economic, political, geographical and geological realities of the different States in question, common trends can be observed regardless of geological resources exploited or to be exploited. For example, the increase in government take (mining royalties, taxes / exemptions on extractive sector companies, government participation in the capital of an operating company), national content, standards for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), as well as environmental and societal requirements.

On the subject of the "government share," it is clear that the decision to revise a mining or oil code sometimes depends on political agendas that do not always take account of changes in the price of raw materials, which may jeopardize the necessary balance between the attractiveness threshold acceptable to the State and the tolerance threshold of investors. When a price increase occurs, like that observed until 2012, many states are tempted to make legislative and regulatory changes in order to capture the additional revenue generated without always understanding the cyclical dynamics of long-term commodity prices. This may have the effect of discouraging investors. The current reforms of mining codes have also sometimes limited the negotiation leverage under mining agreements and have not always taken into account the realities of each country. Beyond reforming the mining codes, it seems necessary to harmonize all the legislation applicable to the mining sector (environmental, labor, taxation, etc.). Sectoral reform would make sense, as it would enable achievement of the desired stakeholder objectives by clarifying the commitments and obligations of economic operators who are, in practice, often confronted with interpreting the contradictions and divergences of the provisions stipulated in the mining codes and in the other codes and legislation.

Responding to the continent's electrification demand challenges

This is now evident: infrastructure development is a sine qua non for African economic development, whether it be transport infrastructure (road, rail or port) allowing the export of extracted or produced resources, or energy infrastructure for generation of electricity. For the energy infrastructure, the associated stakes are enormous in terms of both economic growth and human development. The average electrification rate in sub-Saharan Africa is 31%, which is the lowest level in developing regions, while some 633 million Africans currently live without electricity. Africa's electricity needs are expected to explode due to the continent's demographic growth and its anticipated industrialization. The question of production and consumption within Africa, however, is limited in scale due to the extent of disparities. In terms of consumption, disparities are found at four main levels which can be found in the country, the household income level, the location of the household (whether in rural or urban areas), and more subjectively, how private households perceive both reliable access to the electricity grid and the urgency of their situation. These disparities are also observed in the production sector due to the strong economic differences between African countries (and therefore differences in the degree of electrification of their territories) and the nature of the resources available to each country for electricity generation. For example, South Africa, Africa's largest economy, accounted for more than 33% of Africa's electricity in 2014, with coal generating over 92% of its electricity. Egypt produced 20.70% of the continent's electricity and used gas (74%) and oil (17%) for this purpose. For many other African countries of more modest economic size, the share of hydroelectricity in total electricity production in the country was over 70%.

Table 2: Access to electricity in the developing world

Source: World Energy Outlook (2016) -IEA

Attempting to answer the question of developing power generation facilities in Africa requires solving a multivariate equation: the availability and price of the energy resources needed for electricity generation, the cost of developing and maintaining production and distribution units, the adequacy of these facilities in relation to the needs of populations and industries, and finally, their financing. The existence of negative externalities (pollution, changes in ecosystems) and, where appropriate, the ability to implement effective solutions to manage them are also an integral part of the problem. From this perspective, it is clear that during 2016 there was a strong development of renewable energy based power generation projects (mainly solar and hydroelectric). Largely dependent on hydrocarbons, Senegal has made the development of renewable energies and the liberalization of electricity production a central element of its Emerging Senegal Plan (PSE). In February 2016, Morocco inaugurated the first of the four development phases of the Noor mega solar power stations. While the promotion of photovoltaics was a milestone in 2016, hydropower was not left behind. Among many examples is the December 2016 inauguration of the Ethiopian Gibe III dam. In addition, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project (GERD), a 6,000-MW capacity dam, will help the country to develop an estimated 40,000 MW potential.

The reality of developing energy infrastructure in Africa, as in the rest of the world, cannot originate from a simple opposition between renewable and non-renewable energies. In South Africa, coal is vital to the national economy, the energy sector, and employment. Domestic production, about 260 MT annually, provides almost 70% of the primary energy supply and 90% of the electricity production, and is used as a raw material for the manufacture of fuels. In Mozambique, the country's electricity demand is growing at a high rate (15% per year), while coal reserves are high, leading Ncondezi Energy to plan for the construction of a 1,800 MW integrated mine-power station. Similar projects are also under way in Botswana, Nigeria, Kenya, and Zimbabwe. Finally, on the electrification of the African continent, it is important to note a revolution with multiple facets concerning liquefied natural gas (LNG). By eliminating the physical, geopolitical, and financial constraints that are associated with onshore gas, and by having a favorable environmental balance compared to other non-renewable energies, LNG is an interesting opportunity for many African countries in defining their energy efficiency mix.

Strengthening food security in Africa

While an extreme drought has affected East Africa since the end of 2016, after having affected southern Africa, the question of food security in Africa is unavoidable. Significant progress has been made in this area thanks to the high economic growth rates recorded over the last fifteen years, and to the agricultural policies launched in the early 2000s. At the instigation of the African Union (AU), the apparent willingness of governments to reinvest in agriculture has resulted in an increasing launch of national and regional agricultural development plans, objectives that are subject to regular evaluation. Nevertheless, further efforts are needed to meet the challenges raised due to the population explosion (which means increasing African agricultural production by 60% by 2025 according to the African Union) and climate change.

At the center of this positive momentum is the Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program (CAADP), the agricultural component of the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) adopted by the AU at the Maputo Summit in Mozambique in 2003. In the Maputo Declaration, Heads of State and Government pledged to allocate at least 10% of annual public expenditure to agricultural and rural development. The aim was to reverse the downward trend in agricultural investment, in order to reach at least 6% annual growth in agricultural GDP. In 2014, the Malabo Declaration in Equatorial Guinea reaffirms the commitments made in the Maputo Declaration and adds very ambitious new ones. These include the elimination of hunger and child malnutrition by 2025 by doubling agricultural productivity, halving post-harvest losses and strengthening food reserves. They also include halving poverty by 2025 with the creation of employment opportunities in agricultural value chains for at least 30% of youth, and establishing inclusive public-private partnerships in at least five priority value chains in close association with small agriculture operations. Finally, the declaration also includes the tripling of intra-African trade in agricultural products and services by 2025 with an aim of establishing a continental free trade area, and strengthening the resilience of livelihoods and production systems so that at least 30% of farmers and fishers can withstand climatic and meteorological risks by 2025. The African Development Bank (AfDB) plays a key role in implementing these bold policies. Under the leadership of its new President, Akinwumi Adesina, Nigeria’s former Minister of Agriculture, in June 2016, it adopted its new agricultural strategy called "Feeding Africa," designed to fulfill the Declaration of Malabo and achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals established in September 2015.

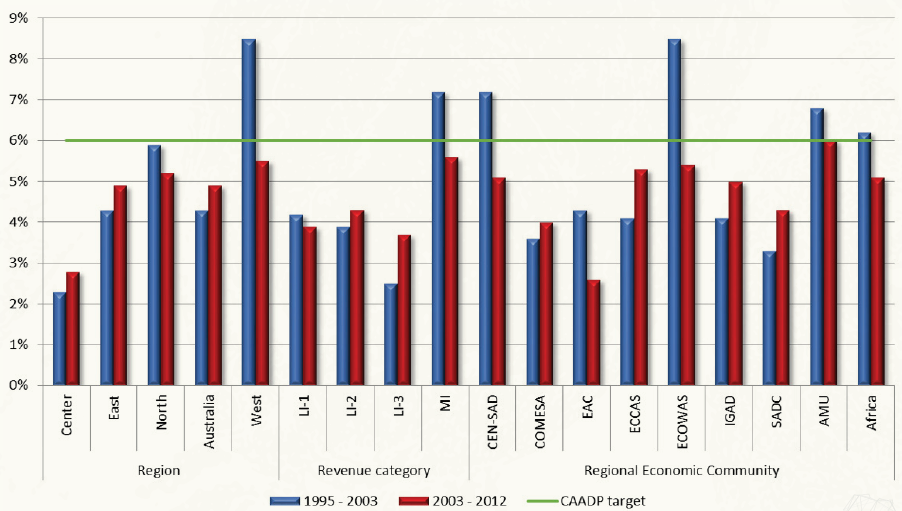

What is the first assessment of these initiatives? According to Agra's latest annual report (2016), CAADP has made a significant contribution to increased support spending and growth in agricultural production and productivity, as well as poverty reduction. It has also improved the process of developing and implementing agricultural policies, with the participation of different stakeholders, including agricultural organizations. However, it suffers from a lack of coordination between the various development actors and a gap between policy design and implementation due to the lack of sufficient institutional capacity. There is also regional disparity since the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is by far the most advanced, with the launch in 2014 of the regional offensive for sustainable recovery and sustained rice cultivation in West Africa that aims for self-sufficiency in production. From a quantitative point of view, a number of objectives of the Maputo Declaration are not being met: over the 2008-2014 period, only fifteen out of fifty-four countries achieved the agricultural production growth target of 6% per year.

Figure 5: Annual growth in agricultural GDP in Africa by country group (%)

Source: ReSSAKS

It is also clear that the number of undernourished Africans continues to grow. The share of the population unable to meet their caloric needs has certainly fallen to 20% in 2014-2016 compared to 28% in 1990-1992, but this reduction is too slow to eradicate hunger by 2025. Another objective of the Malabo Declaration – to triple intra-African trade in agricultural products – will be difficult to achieve by 2025. In 2014, 31% of African food exports were destined for another country on the continent, compared to 28% in 2010. However, these statistics do not include informal, unregistered flows.

In addition, the PDDA contains few provisions for financing agriculture, although this is a major challenge given the low investment capacity of small farms and small food processing enterprises. Price and income regulation is another weak point of agricultural policies in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, CAADP does not explicitly define the agricultural model it intends to promote, both in terms of production systems and operating structures. There is a consensus on the need to increase African yields, which are much lower than in other regions. However, the solutions envisaged to achieve this differ. To this must be added a strong dependence on external financing, which often accounts for the bulk of total public expenditure on agriculture and food, although again there are wide variations between countries. Under these conditions, it is not easy for governments to impose their agricultural development priorities. The essential is in place, however, because the African continent must have a specific development model. Successful, inclusive and sustainable modernization of agri-food chains depends on Africa's ability to feed itself and ensure its development. This success is obviously also an issue for the rest of the world.

Ensure financing conditions for the continent's public and private economic actors

Whether for agriculture, minerals or energy, the issue of financing both structural policies and the actors involved in these sectors is also fundamental. While the 2007-2012 period was particularly favorable for the African continent in this respect due to the combination of accommodative monetary policies in most industrialized countries and high commodity prices, it is no longer the case today. At the root of this change is a different macroeconomic and financial environment and, consequently, a change in the strategies pursued by the main international investors, first and foremost China. This does not mean, however, that a shortage of funding for Africa is now being observed or that it may be feared in the longer term: investors are both more selective and more pragmatic. While debt has traditionally provided the bulk of the commodity sector's financing needs in Africa, traditional creditors, primarily commercial banks, mainly European and South African banks, are now being more selective in processing applications for funding. As such, a deterioration of credit ratings for both sovereign and corporate issuers took place in 2016.

Table 3: African sovereign bond issuances in 2015 and 2016

Sources: BNP Paribas, UBS

(Excluding $4 billion in private investments by Egypt in November 2016)

As for the African private issuers operating in the commodities sector, no international operations were carried out in 2016, unlike the previous year when three financing operations were implemented by the Moroccan OCP Group, the South African Petra Diamonds and Kosmos Energy. On the national debt market, however, OCP Group issued an amount of MAD 5 billion (approximately $500 million), while Northam, a South African platinum producer, raised ZAR 425 million, roughly less than $30 million. A similar finding of relative sluggishness has been observed in international institutions. While the International Finance Corporation (IFC) announced funding for seven projects in the oil and mining sectors in 2015, for a total commitment of $570 million, no operation actually materialized in 2016. The IFC also exercised its put option on the 4.6% it held in the Simandou project in Guinea. However, the institution announced a $52.5 million loan for the construction of a port terminal in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, at a total cost of $152 million in connection with Indorama Eleme Group’s project to build a nitrogen fertilizer plant.

On the subject of bank financing, however, a rebound in activity seems to be observable, despite the difficulty of having a comprehensive market reading due to private transactions. Two loans were granted to South African gold miners, while First Quantum Minerals, a diversified mining group, was able to raise $1.8 billion from French and British banks. In the project-financing category, $823 million was granted by the BNP Paribas, Société Générale, and Natixis consortium to the Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée (CBG); and the Australian bank Macquarie granted $120 million to the Canadian company Semafo, which develops the Natougou gold mine in Burkina Faso. Also in 2016, several bank loans were also a priori granted to companies operating in the oil sector in Africa for a total amount of $5.7 billion.

In the equity segment, significant mergers and acquisitions were also recorded. Among them is the sale by the American company Freeport-McMoRan of its participation in the huge Tenke Fungurume copper mine in the DRC for $2.65 billion. In October 2016, the Anglo-Australian group Rio Tinto announced that it had reached an agreement to resell the shares it held in the joint venture Simfer in charge of developing the Simandou project. As a result, 46.6% of the joint venture was sold to China Aluminum Co (Chinalco), which already owns 41.3% of the project capital. Beyond these large-scale operations, which are widely publicized, it is interesting to note a week recovery of initial public offerings (IPOs) of "junior mining companies" on the stock market. From this perspective, while China has been at the heart of mergers and acquisitions in 2016, it should be noted that investments were made primarily in projects that are already in operation and not in exploration or development. The renewed momentum demonstrated by some Australian mining companies by strengthening their exploratory investments in the African subsoil is probably an indication of an improved future outlook.

Conclusion

Despite some counterexamples such as cocoa, the upward trend in the price of commodities observed in 2016 and in the first months of 2017 has clearly been good news for the many African producing countries. Although it has leveled off since 2015, the economic growth of the continent's best performers was also above 6% in 2016, which attests to their strong economic resilience in a still difficult global context. A satisfacit cannot be fully justified for several reasons. This increase must first be seen in light of the price collapse observed in 2014 and 2015 and cannot hide the fact that the peaks reached in the first part of the decade are still remote. Secondly, the rise in prices did not make it possible to significantly improve the public finances of many countries and, according to the IMF in particular, considerable budgetary efforts have yet to be made. Finally, just as Brent crude, in particular, this trajectory remains unstable because of the renewed speculative activities that partly involve it. It should also be noted that under the infamous resource trap, the high volatility of prices is a source of macroeconomic instability almost as much as their low prices. In this sense, the fundamental and complex question, which has been asked for decades about the African continent, concerns its growth model. This calls for several remarks. It is first of all accepted that, for obvious reasons, the model cannot be based solely on the export of unprocessed materials. However, this does not necessarily mean that investment in primary processing activities is, by nature and for all African economies, a profitable option. The economic diversification of the continent also requires financing, implying the raising of funds in international markets. In a monetary context that is likely to tighten with the gradual normalization of Fed policy, the ability of African countries to offer the best macroeconomic, fiscal, legal, and political prospects is essential. There remains, however, a central issue that African countries still need to address concerning the better development of intra-continental trade, particularly in agriculture, which is acknowledged as a condition for their greater resilience to the upheavals of the world economy and as a key stage in their economic and social development. We expect that the 2018 edition of the Arcadia report will be able to take stock of this.