Rethinking development finance: towards a new “possible trinity” for growth?

Development finance is an issue that typically concerns developing countries where numerous, grave socio-economic problems persist, including – and not among the least – the need for stable development finance in higher quantity and of higher quality. However, development finance could also be used today as a growth-enhancing concept applicable to advanced economies, to boost their growth and help their social inclusion. It could contribute to rebalancing macroeconomic policies and move them towards a new “possible trinity”: growth based on higher productivity, growth that favours stronger social inclusion and growth that is friendlier to the environment.

Are the long-term development strategies that worked for developing countries using development finance useful now for advanced economies?

The subject of this panel is the need to rethink development finance. This is typically a developing country issue. We all know that there are still numerous, grave problems in developing countries, including – and not among the least – the need for stable development finance in higher quantity and of higher quality. My point here is a bit different: “development finance” could be used today as a growth-enhancing concept applicable also to advanced economies, to boost their growth and repair their social fabric. It could help rebalance macroeconomic policies and move them towards a new “possible trinity”: growth based on higher productivity, growth that favours stronger social inclusion and growth that is friendlier to the environment. Let me explain.

A (very) short assessment of development finance in developing economies

Let’s take for a moment the textbook view about what development finance was supposed to deliver in the last two or three decades: first, it was conceived as a financing mechanism. It used international development institutions (eg the Bretton Woods institutions) to channel rich creditor country aid and/or lending to developing countries, in the absence of sufficient local savings and mostly under some form of conditionality. Second, it was also a type of contractual incentive, a way to buy “reforms” in developing countries. Overall, it was meant to be an accelerator of the virtuous cycle of development, a reasonable bet on future higher growth in developing countries. Hence, the process was constructed to be mutually profitable for lender and borrower.

In practice, development finance worked by funding good investment projects (and policies). It provides predictable rules-based official development assistance, in the form of regular budgetary transfers from advanced economies to developing countries. The financing could come directly via international financial institutions (eg multilateral banks such as the World Bank, and many regional development banks), but also non-profit organisations (NGOs), humanitarian institutions, etc. Then, when/if successful, development finance was supposed to trigger additional private capital investments provided the recipient developing country also put in place policies that contributed to delivering positive spin-offs from received assistance – in particular, adequate infrastructure to promote growth and higher productivity. With all that aligned and working well, development finance would trigger a win-win: the developing country would progressively substitute foreign direct investment for grants, official development aid and loans. Next, the successful developing country would be in a position to access global debt and capital markets. Eventually, this process would contribute to consolidating a stable local macroeconomic and socio-political environment. Local businesses would thrive, growth would take off, new local markets would increase global demand, and all countries would win by converging towards common higher living standards – the happy conclusion of a globalised world of convergence to wealth and prosperity.

Without naively buying into the “rosy fairy tale” picture above, take a cold look at the big picture for the last few decades: some parts of the narrative above did indeed happen. Part of this story applies to China, India and East Asia, although, admittedly, Asian countries did not develop because of development finance but through the pursuit of sound macro policies, together with some state intervention, industrial policies, etc. The strict role of development finance is also less clear in Latin America and even less in Africa, etc. Overall, the development process is more complex than just financing; it took time and a few crises in the 1980s and 1990s. But the intertwined processes of development and “globalisation” brought many benefits, chains of production were redesigned to be global, billions of new consumers emerged in developing countries, and lower production costs pulled down the prices of many goods in advanced economies. Most developing countries learned how to integrate into world trade and financial flows and to benefit from socio-economic reforms – opening up, having access to private capital markets, etc.

Naturally, development finance faces many problems and critiques left, right and centre. To some, it condoned local corruption and poor governance; to others, conditionality led developing countries to apply some policies (eg financial liberalisation) too hastily. But we learned. After decades of studies, we now know that sounder institutions matter when it comes to fostering development. We are aware of the fact that each country might have its own very specific “binding constraint” to grow that supersedes other factors; and we understand that there are different possible development financing “cocktails” comprising more or fewer grants and more or fewer loans lumped with more or fewer public private partnerships (PPPs). The seminal idea was and still is: development finance could be seen as the official sector side of “financial globalisation”. It allows developing countries to buy time and create incentives for local structural reforms; combining it with sound macroeconomic policies (and some luck) can ignite sustainable growth development.

The other side of the globalisation coin in advanced economies

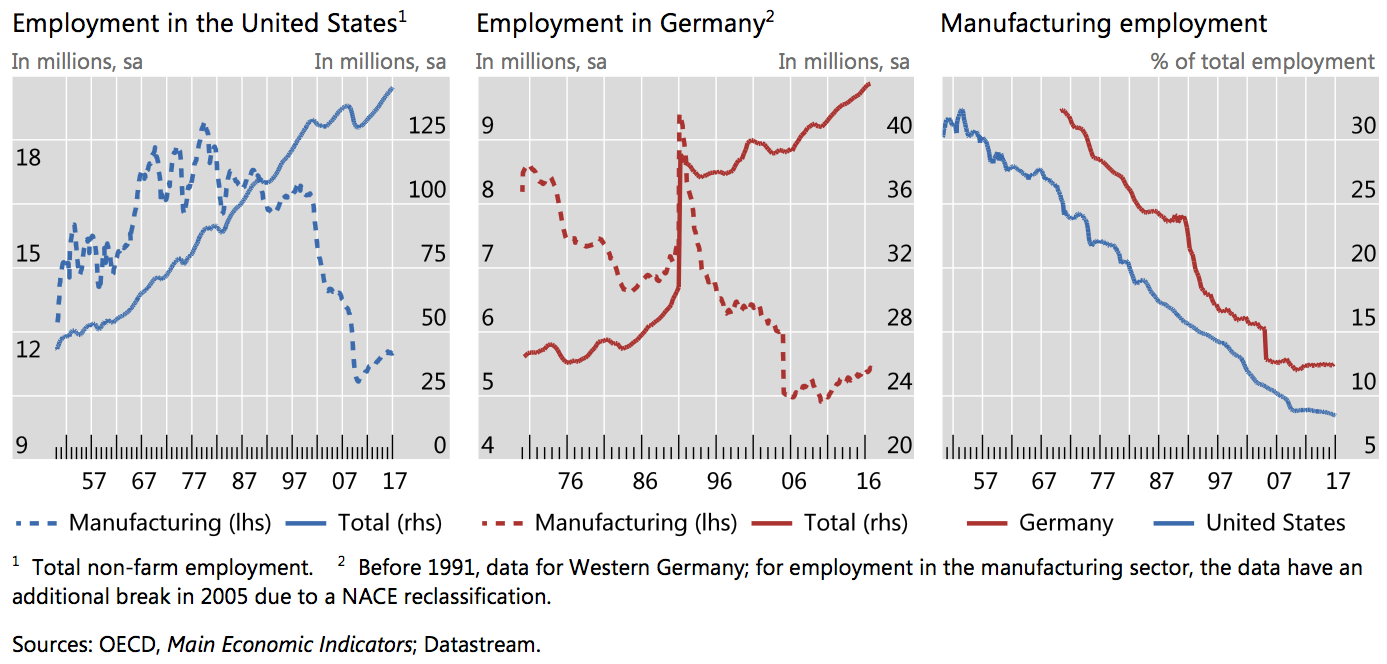

The paradox is that one aspect of the above-mentioned “rosy story” that was perhaps neglected – and did not fully work as a win-win – affected advanced economies. In particular, globalisation exacerbated specific socio-political problems in advanced economies. For example, industrial jobs fell by about a third to a half, and some were indeed transferred to developing countries. A great part of this trend, however, is not a new trend but one that is common to many advanced economies (Graph 1). A large body of literature explains that the reduction of manufacturing jobs is the result of structural change, ie technological improvements. In addition, overall, the loss of industrial jobs was compensated by the creation of other jobs. But it did not prevent the creation of “pockets of high unemployment” in many advanced economies. For our discussion, it should be noted that these losses and deindustrialisation were (and still largely are) “perceived” mostly as trade-related.

Graph 1 : Employment in manufacturing in Germany and the United States

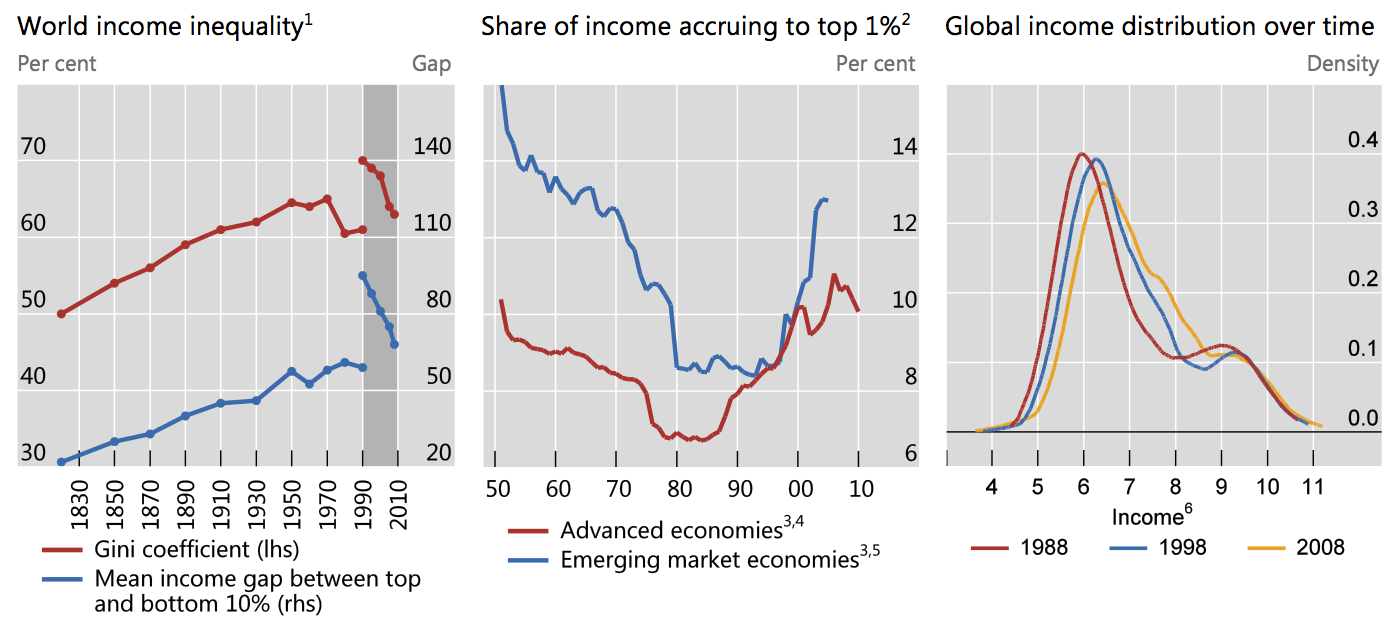

In any event, more than simply exacerbating income inequality in advanced economies, which was trending up even before the global financial crisis, these technological/structural changes also affected specific segments of advanced economies’ middle class. Recent studies have confirmed that globalisation reduces inequality across countries but in many cases increases inequality within countries (Graph 2).

Rising inequality and these “pockets” of high and durable unemployment that fed discontent were factors adding to the “perception” (and the reality) of the growing income divergence between the “super-rich” (the top 1%) and the average person (Graph 3). Those characteristics eventually produced frustration and changes in socio-political behaviour, acting as an impediment to the traditional “convergence to the mean” in our societies once dominated by middle-class median voter behaviour. Analytically, its consequences lead to what has been labelled an impossible trinity between democracy, global markets and the capacity to conduct reforms and pursue independent socio-economic policies.

Graph 3 : Wealth inequality is increasing within advanced economies Share of wealth accruing to the top of the distribution, 1810–2010, in per cent

To be fair, among advanced economies, the policy answer to that situation (ie achieve higher productivity through reforms) was activated in some countries. But a combination of other factors also engendered complacency and delayed or prevented reforms. Financial globalisation might, since the mid-1990s, have acted like a “veil”. It facilitated the relatively easy financing of “large current account imbalances” in some advanced economies (eg the United States) by surplus-prone developing countries (eg China). Lax financial regulation in advanced economies allowed resources to be allocated to less productive sectors of the economy (eg housing and its subprime segment). Financial sophistication perhaps helped hide the increasingly pervasive trend of declining productivity. In other words, globalisation enhanced productivity in many developing countries and accelerated the relative speed of their structural transformation, but it might have contributed to a degree of illusion in advanced economies, allowing a poor allocation of resources and reducing these economies’ capacity to reform. We ended up with other problems too: rigidities and limited acceptance of adjustment costs, inadequate policies to promote retraining and labour mobility across regions, insufficient use of taxation as a redistributive tool, etc.

The recent electoral ”surprises”, ie the outcomes of the Brexit vote and of the US presidential election in 2016, can be seen in that light, as part of a rising wave of ”populism” in many advanced economies. These events can be interpreted as the result of the accumulation of negative factors burdening the old social structures in advanced economies. The above-mentioned (real and perceived) effects of globalisation added to the (real and perceived) threat to social status and national identity and the lasting fallout from the global financial crisis. All that aggravated local problems, especially when they were compounded by tragic events related to modern terrorism.

Why bother? Well, if advanced economies do not reform and strengthen growth in the long run, they will be increasingly incapable of addressing their own socio-economic problems. And those might be compounded by significant population movements, as they will remain very attractive to migrants from developing countries (especially those affected by conflicts). This context might turn many policies even more risk-averse and isolationist. The popular mindset in advanced economies has been undergoing a significant shift towards a more inward-looking perspective, shying away from multilateral cooperation and from a number of critical problems on the global agenda.

This new backlash against globalisation, trade and any form of international cooperation might get stronger. If this new mindset gets entrenched, many of the policies advocating collective action and global public goods that have been chosen in the post-World War II period might be abandoned: for example, fewer barriers to trade, financial regulatory cooperation, global security, shared socio-political-economic stability, shared concern over issues related to climate change.

Thus, to further strengthen international cooperation, growth prospects in advanced economies need to improve. That is precisely where rethinking the nexus around development finance could help. In fact, advanced economies can reform and change their mindset if they reach for some of the old recipes that worked in developing countries. I will come back to that in a moment.

Can the development finance concept be useful for advanced economies?

One of the problems that development finance tries to address is what economists call a “time inconsistency” problem between policy action and its results. Reforms, transformations and complex phenomena such as globalisation produce winners and losers across a certain time horizon and different types of agents in the economy. In some cases, for example, fiscal transfers can be used to compensate for income losses associated with structural reforms. Indeed, usually the costs, disruptions and uncertainties would appear immediately, without a corresponding capacity to offset them. Sometimes the tangible, positive effects of reforms cannot be perceived within a reasonable time horizon. Similarly, the distributional consequences of reforms might disproportionately affect specific groups. It is an old issue in the welfare economics literature and one which is carefully examined in detailed analysis of the political economy of reforms. It is also covered in studies of why reforms can be blocked by special interest groups. In many developing countries, the response to these challenges in a context of limited fiscal space for transfers was to use external debt (in the form of development finance) to support the costs of these transition periods.

If we fast-forward to today’s situation, many advanced economies might be facing a similar problem. They know that they need to implement structural reforms to reignite sustainable growth

(eg more factor market flexibility, more openness to trade, more efficient allocation of public funds). But they also know that, if undertaken in the first year of an electoral mandate, reforms are unlikely to produce significant positive outcomes before the end of any advanced economy’s typical electoral cycle (usually four to five years, if not less). Many realise that they face more stringent fiscal constraints, especially after the global financial crisis, making it more difficult using fiscal policy to address the redistributive problems that structural reforms can bring. Therefore, these fiscal and political constraints result in procrastination of structural reforms: they are either too timid, ill designed and unbalanced to accommodate conflicting interests, or simply not carried out.

So, could the long-term development strategies – eg using fiscal transfers and debt – that bought time and financed reforms in developing countries now be useful for advanced economies? Could the principles behind development finance (eg creditor-conditional transfers, loans arranged through specialised institutions, compensating potential losers to allow reforms to be voted on and implemented) be applied in advanced economies too so as to engineer reforms and strengthen the coherence of their social fabric?

What is the fiscal space for transfers and finance reforms in advanced economies?

The problem of adding more debt to finance reforms in advanced economies is that the global financial crisis has also significantly reduced their fiscal room for manoeuvre. Admittedly, it is a difficult question since debt dynamics are influenced by several factors: ”estimates of the margin for fiscal stimulus based on the calculation of fiscal space are very sensitive to assumptions and subject to uncertainty, and therefore could overestimate true fiscal space”. Using an upfront fiscal instrument could be useful to achieve any of the various goals of reforms – that is, to redirect resources to sectors and activities with higher productivity potential. But currently, many advanced economies have limited fiscal space to increase debt. With total public expenditures amounting to 40–50% of GDP in a number of advanced economies, one obvious question is about the quality rather than the quantity of public spending. This is even more the case in early 2017 in a rapidly changing environment where risk premia have risen for some sovereigns due to uncertain political outcomes in Europe. Hence, advanced economies need to weigh carefully how to use a combination of transfers, reallocations and debt to foster their own structural reforms to enhance their much needed productivity gains.

Each advanced economy needs to conduct a thorough examination of its own fiscal space. Some advanced economies have more fiscal room but are reluctant to use it. Those that perhaps have less room are those that might be more tempted by more expansionary policies that might become unsustainable. A detailed (and continuously updated) assessment is necessary to gauge the financing needs and means for longer-term structural reforms. The analysis should examine how sustainable debt dynamics will be with current very low interest rates but also under future scenarios with a higher term premium in advanced economies.

Financing reforms in advanced economies: towards a new “possible trinity”?

So, where are we? There is a recognised need to increase growth prospects especially in advanced economies today using a combination of structural reforms and investment in productivity-enhancing projects. It has been widely discussed that investing in infrastructure would help productivity. We could also add new technologies (eg to reduce our carbon footprint). Initiatives to address both of these needs should also contribute to increasing employment and fostering stronger socio-economic inclusion. But there is a relatively limited political appetite for direct debt financing of these initiatives/investments, as profitable as they may be. It looks like a catch-22 situation: we know what to do but do not have the immediate financial resources to do it. Some might fear that advanced economies could now shift from excessive reliance on monetary stimulus into fiscal complacency. Thus, there is a need to examine how these initiatives could be financed. And while we’re taking a look at sustainable debt dynamics, focusing primarily on public debt, it should not preclude us from also analysing private debt in connection with the country’s overall fiscal space. Private and public sector balance sheets are increasingly interdependent, and we know how both are subject to feedback loops. Let me provide some directions for further discussion below.

First, with all its own caveats, some additional parafiscal space can be carefully considered – for example, using various forms of explicit and transparent public guarantee and/or the balance sheets of multilateral institutions. Thus, if a possible route is to use multilateral balance sheets, there are several such institutions operating in advanced economies (the European Investment Bank being the largest, and the Juncker Plan being perhaps a useful model to revisit and expand). This route takes us back to the risk-sharing nature of the Bretton Woods institutions at their inception.

Second, as emphasised by many academics, think tanks, international institutions, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) and the G20, there are cases where private bond issuance could also help. This is valid for infrastructure (eg using special entities and/or private-public partnerships). It can also be envisaged for new technologies, as mentioned earlier. Take, for example, what is now termed “green finance” (Graph 4), with all the caveats associated with a self-serving denomination. Figures that are more recent than those in Graph 4 show that the green bond market represents about $170 billion in outstanding bonds. Issuance in 2016 totalled some $90 billion, doubling the amount for 2015. In addition, there are many business opportunities arising from changes in market appetite for new indices that incorporate “green” factors, green exchange-rated funds and exchanges listing green securities. Various sources confirm that there are placement room and demand for huge investment to get us to a low-carbon footprint (eg estimates of about $13.5 trillion in the next 15 years).

For both cases – multilateral development institutions and green bond financing – would that imply some form of financial repression? Not necessarily. The demand for these assets exists, and it could be relatively stable and not subject to excessive market volatility. In addition, the quality of many of these assets is excellent: the environmental credit risk composition indicates that about 78% of aggregate green bond issuance since 2007 is low-risk (Graph 4, right-hand panel). Moreover, there are institutions such as pension funds and life insurance companies whose current investment in safe sovereign assets is returning negative or very low yields. Higher returns could come from these new debt instruments issued by multilateral financial institutions and/or green financing. Notwithstanding the ongoing normalisation of monetary policy in the United States, we are still in a period where relatively low (even negative) yields will persist for quite some time in other jurisdictions. Would that be the silver bullet to reignite growth in advanced economies? Obviously not, but reigniting growth through investment in new technologies is most likely more sustainable from a macroeconomic and environmental perspective than any of the previous consumption-led and household debt-based recoveries. At least, we should hope that some useful components of this strategy begin to shape up.

Graph 4 : Green financing

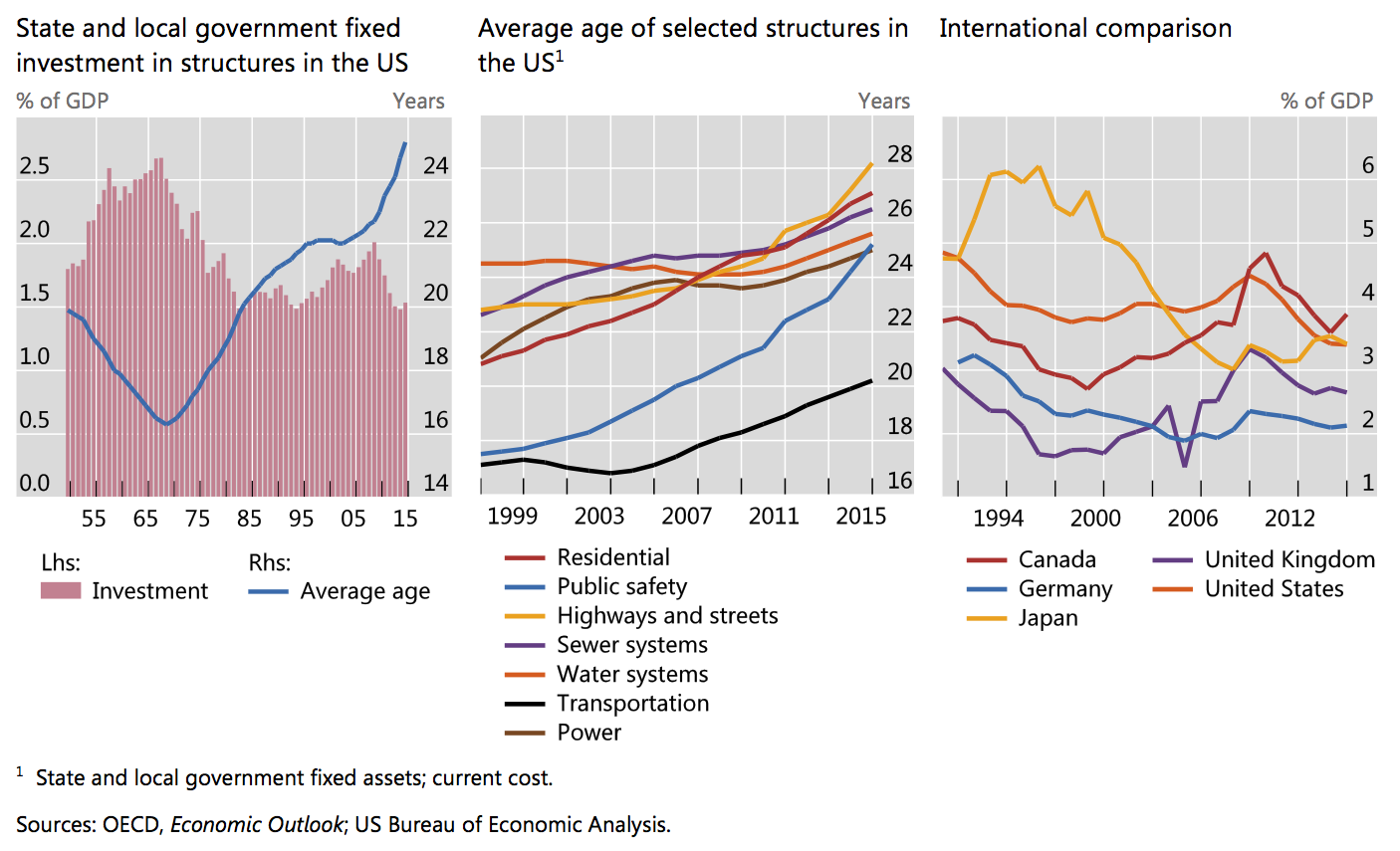

Third, beyond investment in “green” projects and infrastructure, there are quite a number of other useful projects to strengthen social inclusion. If policies want to address the social dislocation mentioned above, several directions can be envisaged. The obvious ones that come to mind revolve around tackling social discontent on the peripheries of large agglomerations where incidents have flared in many advanced economies (eg the United States and European countries). The variables to control include: (i) the higher than average rate of youth unemployment in many, if not all, advanced economies (Graph 5); and (ii) the equally important problem of infrastructure obsolescence that most often affects disproportionately “poor districts” in large urban agglomerations in our economies. More granular data are needed, but overall the lack of investment in infrastructure can be measured by the lack of state and local government fixed investment in structures (Graph 6), which is leading to their obsolescence (increasing average age of selected structures, declining portion of GDP spent) and greater operating risks. Addressing this issue will reduce costs and improve productivity. It could also rebalance life quality and improve the sense of fairness for those receiving an insufficient part of the supply of public goods in our societies. Moreover, proactive policies to tackle youth unemployment – which include structural reforms in labour markets – can be better explained and disseminated as a necessary component of policy frameworks contributing to greater social inclusion.

Last but not least, the investments mentioned above can also be complemented by the delivery of other public goods and services (eg in education, health and social services in advanced economies’ more fragile communities) that can help enhance human capital and foster future productivity but also strengthen our social fabric. Such social programmes combating the spiral of income loss, unemployment (especially youth unemployment) etc are already in place in many advanced economies. They could be enhanced.

Graph 5 : Unemployment rate in advanced economies Q3 2016, in per cent, seasonally adjusted

Graph 6 : Government investment in fixed assets

In a nutshell, advanced economies might need, among many other things, to reduce their own pockets of social exclusion and poverty thus shadowing to some extent the experience of emerging market economies. That means restoring an adequate, homogeneous and well distributed supply of higher-quality public goods the efficiency of which should complement private spending. That will of course have long-term effects on productivity, but also on the cohesion of our social fabric.

This discussion casts us back to the 1950s–60s, when the debate was on fostering development by proposing a “big push” to investment in developing economies. This was Rosenstein-Rodan’s intuition calling for the use of externalities produced by the ambitious industrialisation of several sectors of the economy. Today this idea could feed on our need for an energy transition, and for stronger social inclusion, as a way to revisit the “big push” argument: reshape our economies towards a new “green” and low-carbon growth model with new services and new technologies to increase social inclusion.

This would naturally require more studies to be conducted in order to determine the feasibility and economic rationale for such a strategy and its components. Detailed implementation plans would be needed with analysis of the impact on public finance, especially from a general equilibrium perspective, etc.

Such a coordinated effort is challenging, especially now that international cooperation seems to have gone out of fashion. But the consequences of not being able to reboot advanced economies’ growth have already been felt throughout these post-global financial crisis years, during which macroeconomic policies in advanced economies have (almost) exclusively used monetary policy to try to engineer growth and inflation while hoping that structural reforms come about spontaneously. We have reached the limits of that.

Conclusion

The global financial crisis might have provided us with a good opportunity to reassess our growth model, its risks for our environmental sustainability and its socio-distributional consequences. It might be a good time to rethink this course and use the old recipe of development finance that worked in developing countries to think through the financing of structural reforms and new investment projects.

We could, then, be on the way to constructing a new “possible trinity”: (i) increasing growth through new investment that focuses on productivity and a smaller carbon footprint; (ii) strengthening social inclusion; and (iii) using the window of opportunity arising from the demand for higher yields on long-term safe financial instruments. If we manage this prudently and responsibly, higher growth, stronger social inclusion and “higher-quality” sustainable development can ensue.