The Global Outlook, Trade Conflicts and Africa

After a long spell of slow growth in the wake of the global financial crisis, the global economy was gaining speed over 2016-2018, but this recovery is now in some danger. The likelihood of imminent recession is low but growth will be slow over 2019-2020, and growth next year presents many uncertainties. Growth is supported by the consumer for the time being, but business has become very nervous and something will have to give. There are significant and specific risks in the large economies, but the biggest risk, intensification of trade disputes, is global in nature. The less-than-rosy outlook will certainly impact Africa, counseling caution.

Since early in 2018, a succession of reports from the major international agencies and private forecasters have down graded the outlook for 2019. Whereas the IMF’s World Economic Outlook of April 2018 called for growth of world GDP and trade of 3.3% and 4.7% in 2019 respectively, the latest World Bank forecast, issued in June, calls for growth of just 2.6% in 2019 for both variables . In a diverse global economy which approaches 90 trillion $ in size these are very large forecast changes in a relatively short time. All variables in this text are expressed at market exchange rates and in real terms unless otherwise stated.

The change is particularly disappointing and worrying following a long spell of slow growth. In the 20 years prior to the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2008, world GDP grew at 3%, and the recovery from the crisis was protracted and slow, with world GDP registering just 2.2.% growth a year over 2008-2016. That meant that world output never recovered the loss from the crisis relative to its long-term trend. There followed 2 years, 2017 and 2018, where world GDP finally returned to its pre-crisis trend, and, since the recovery was broad-based, elicited hope that the expansion would continue. The turn came over the course of 2018 and the latest data dashes those expectations.

Recent Data

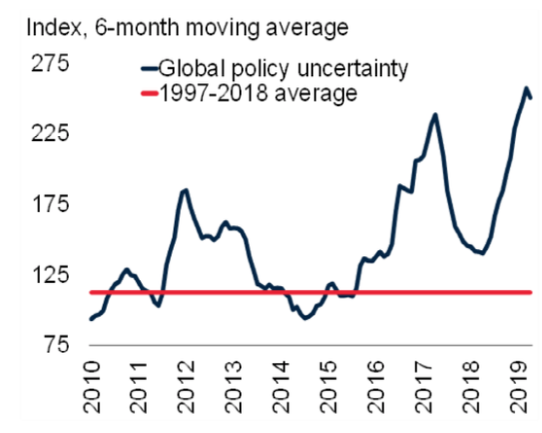

At the core in the change of sentiment is a surge in uncertainty over economic policy as measured by internet mention of words such as “crisis”, “risk” , ‘Uncertainty” etc. (Chart 1).

Chart 1 : Global policy uncertainty

Source : Baker. Bloom. and Davis (2016); Election Guide; Haver Analytics; International Foundation for Electoral Systems; National Sources; Peterson Institute for International Economics; U.S. Census Bureau; World Bank.

Although some of the uncertainty related to monetary, fiscal and regulatory policies, the biggest factor is the threat of trade wars, to which we return later.

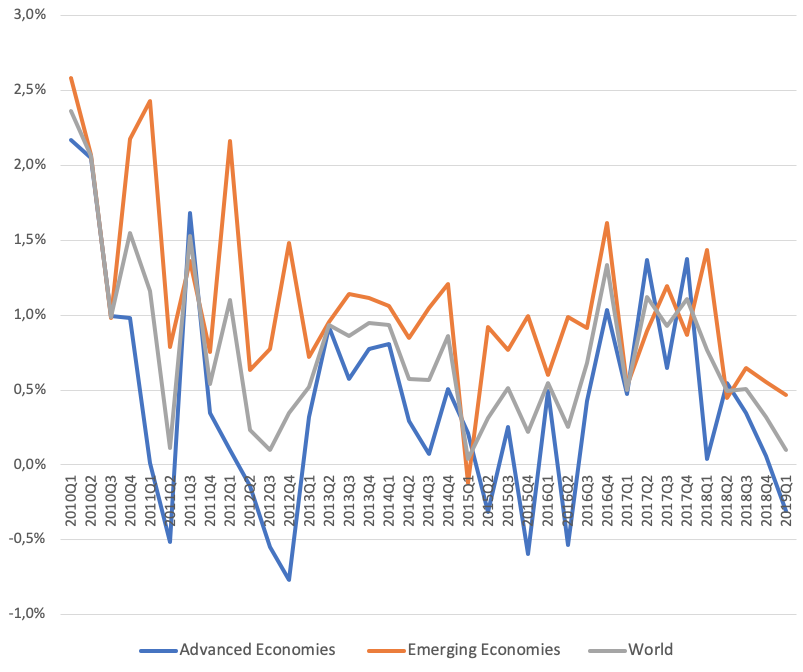

The change in direction of some of the most widely followed short-term indicators is illustrated in charts 2 and 3 below. The momentum in world trade and industrial production which exceeded 4% a year in 2017, is now zero or in negative territory. Purchasing manager surveys, which provide excellent leading indications of the short-term outlook, now expect stabilization in manufacturing and declining export orders from strong expansion at end 2017, start of 2018.

Source: CPB World Trade Monitor and Author’s Calculation. May 2019

Factors Supporting Growth

It is important to note, and is not sufficiently said, that absent strong headwinds, modern economies tend to grow. This tendency remains strong during the present era of technological advance, globalization and catch-up in the developing world where demography, while slowing, continues to provide a strong impulse. Moreover, while some economies, including possibly the United States, are approaching full capacity utilization, there remain large relatively untapped resources of labor and plant in developing nations and in several advanced countries where the recovery from the crisis is still incomplete.

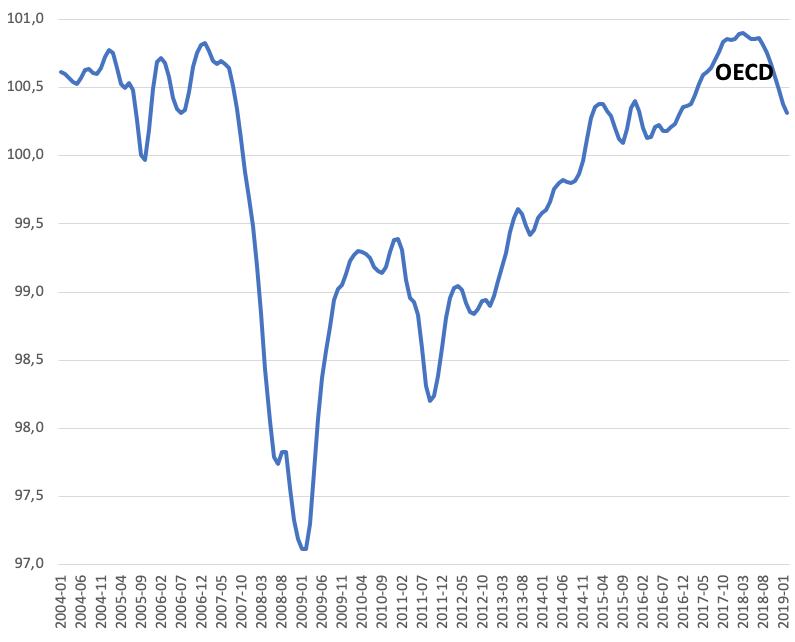

Growth remains resilient today largely on account of consumers, whose confidence recovered gradually in the wake of the global financial crisis and remains at high levels, although it has dipped a bit in the OECD countries since the turn of the year (Chart 4). Consumer sentiment in OECD countries remains positive on account of low and/or declining unemployment, subdued inflation, gains in real wages and sound household balance sheets. The strength of consumer demand also helps account for the resilience of the vast service sector, which is also less directly affected by trade uncertainties than manufacturing.

Chart 4 : OECD Consumer Confidence Index

Source: OECD Database. 2019

While, now that much of the effect of US tax cuts and expenditure increases is behind us, fiscal policy plays a secondary, although still mildly stimulative role in some countries [IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2019]. Based on prior experience China, which is the country most directly affected by the trade uncertainty, may see large counter-cyclical fiscal and monetary measures than many expect.

Importantly, Central Banks began to take note of the weakening evident in short-term indicators already in mid/late 2008, and have signaled a change in posture, from progressive data-driven tightening, to a pause, and most recently to the possibility of rate cuts or renewed quantitative easing operations where interest rates are near the zero bound. The change in posture in monetary policy was quickly reflected in pausing and then declining bond yields and bond spreads, as well as renewed inflows into higher-risk interest-rate sensitive asset. This trend has helped emerging markets, which have seen a sharp decline in spreads since the turn of the year and a resumption of net inflows of portfolio capital following large outflows over the course of 2018.

Headwinds and Risks

There are, as always, country specific constraints and risks that can impede growth over the next two years. Thus, concerns about a large build-up of debt in the corporate sector in China remain. The US recovery is now ten years old and is supported by large scale fiscal stimulus which is largely behind us. At the same time, the US fiscal deficit has surged despite the economy’s solid growth and now accounts for 6% of GDP, a level that many consider unsustainable. The coming sales tax increase in Japan may dampen growth as happened during the last episode. Europe continues to suffer from the protracted Brexit difficulties and from a resurgence of populist parties across the continent, some of which were reinforced by the recent European elections. Some large emerging markets such as Argentina and Turkey continue in difficulty, while others, namely Venezuela are in default or on the brink of default on their international debts.

Each taken on their own, these individual country risks appear manageable. The picture changes markedly if these vulnerabilities were exposed simultaneously by a large global shock, namely a trade war. As chart 7, from the World Bank’s June 2019 Global Economic Prospects, shows, there has already been a significant increase in the applied tariffs of the United States, from under 2% to over 4%, and a much larger hike is under consideration should tariffs be applied to all imports from China and to imports of automobiles from all countries other than NAFTA members Canada and Mexico. Chinese applied tariffs have also increased significantly in retaliation to US measures, while tariffs in the EU and Mexico have edged up.

Chart 7: Average imports tariffs in G20 countries

Source : World Bank, 2019.

The tariff increases are already having a big effect, as can be seen in China’s imports from the United States, which were growing at 10% a year in mid-2018 and are down by almost a quarter relative to last year in the most recent data available [Chart 8].

Chart 8: Decline in Chinese imports from the US

Almost certainly such a big shift reflects not only the direct effect of tariffs but also the reaction of Chinese consumers and firms to perceived US unilateral measures and, possibly, to non-tariff measures by the authorities.

Impact of Trade Conflicts

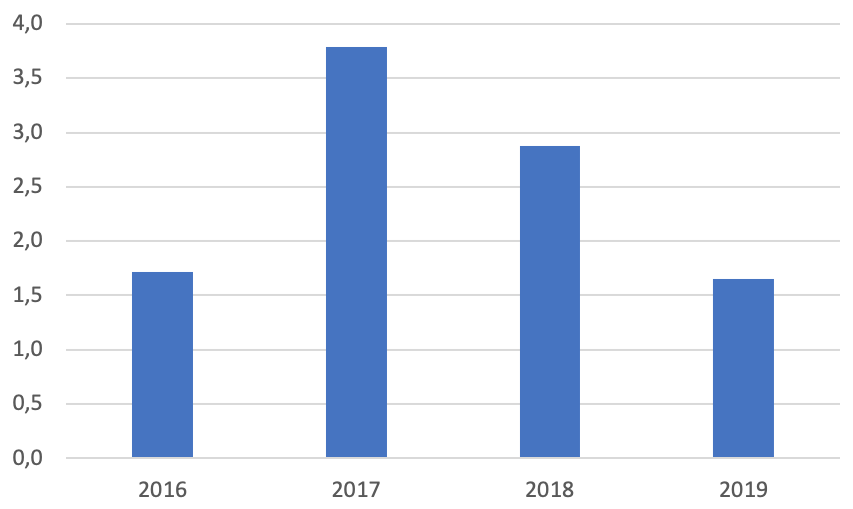

As I have already covered in a separate brief (Dadush, PCNS, May 2019), the aggregate welfare effect of tariffs is usually calculated to be small because tariffs – as is so far the case – have covered only a small amount of trade and they essentially represent a transfer from consumers and importers to the government, which sooner or later flows back to consumers. Nevertheless, tariffs can have a big short-run depressing effect on economic activity because of the uncertainty they generate and because they redistribute income in ways that are significant from consumers and import-dependent firms to the government, and also affect exporters when trading partners retaliate. As Chart 9 shows, the uncertainty has important repercussions on investment, which in advanced economies, is projected by the OECD to grow in 2019 at less than half the growth seen in 2017.

Chart 9: OECD Investment Growth

OECD, database 2019

This effect of tariffs on ‘animal spirits’ is difficult to quantify, and all estimates should be taken with a grain of salt. In the October 2018 edition of the World Economic Outlook, for example, the International Monetary Fund has estimated that a high-intensity trade dispute (consisting mainly of China and the US applying 25% tariffs on all their bilateral trade and the US applying 25% tariffs on all its car imports and retaliation by its partners) could depress economic growth by 0.4% after one yearhttps://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2018/09/24/world-economic....

Unfavorable as these scenarios might be, things could turn out to be worse still if the conflict escalates. Above all, investors fear extreme outcomes that could entirely disrupt global supply chains. The uncertainty over tariffs is most damaging when it calls into question not only domestic conditions but the viability of the global trading and investment system.

Even prior to the events of recent days, great damage has been done to the WTO by the United States’ refusal to replace members of the Appellate body, by its decision to impose tariffs on aluminum and steel for its allies (invoking national security), and by its use of Section 301 to proclaim a first round of tariffs against China – in clear violation of WTO rules. The negotiations between China and the United States are being conducted outside the WTO framework for settling disputes and widely reported measures included in the draft agreement – such as Chinese promises to buy more soybeans, natural gas, and aircraft from the United States – would violate the non-discrimination principle of the organization. The United States is also widely reported to insist on maintaining tariffs against China as a measure to ensure compliance with the agreement, which would also violate the WTO rules. By agreeing to negotiate in this way, China and the United States undermine the organization that many expect them to lead.

While many recognize that trade benefits consumers and enhances productivity, protectionist and free-trade interests are typically quite evenly balanced in countries across the world. The examples of the United States – stakeholder of reference in the rules-based system – raising tariffs, and of China – the world’s largest trader after the European Union – doing the same in retaliation, all outside the WTO system, inevitably tips the balance in favor of protectionists everywhere.

As many believe, the trade dispute between China and the United States is only partly about trade, and perhaps it is not even mainly about trade - like the regional proxy-wars between the Soviet Union and the United States during the cold war, the underlying motive is not so much about a specific measure but about great-power competition. It follows, as others have also predicted, that even if this trade episode is resolved amicably, confrontations will recur – and some of these are likely to unfold outside the trade arena, where they may turn out to be even more dangerous.

The Global Forecast and Africa

Given the considerable forward momentum of the world economy, supportive monetary and fiscal policy and low unemployment, it is safe to predict a reasonable growth outcome in 2019, albeit one less positive than 2018 [Table 1]. However, given the uncertainties, especially those due to the trade conflict, the crystal ball becomes much murkier in 2020, where the numbers – while somewhat reassuring due mainly to the effect of looser monetary conditions on growth in emerging markets less affected by the trade conflicts so far – are frankly speculative.

Table 1: GDP and Trade growth forecast for 2019 and 2020

Source: Author’s Calculations

It now looks quite likely that world trade, which had recovered a sizable growth premium over world GDP in 2017-2018, will again grow at rates close to or below those of world GDP. In the aggregate, world trade is a wash of global demand since one country’s exports are another country’s imports. However, for individual nations, especially for small open economies such as those in Africa, which often face a foreign currency/foreign debt constraints, the fact that they cannot count on rapid growth of external demand is very significant. African nations depend disproportionately on commodity prices, which in turn are affected by the growth of Chinese demand – expected to slow- and the global business cycle, and they also depend disproportionately on demand in Europe, Africa’s most important trading partner, and also the world region, together with East Asia, most dependent on international trade.

Commodity prices are lower this year compared to the moderate levels of last year and are expected to remain soft. Surging oil production in the United States due to shale technologies is a major contributor to lower oil prices this year. Low oil prices help many smaller African economies which are net oil importers and which are expected to continue to record respectable growth rates near 5%. But they will also hurt several of Africa’s largest oil exporters, such as Angola and Nigeria. These economies are also beset by major internal challenges, as is South Africa, which means that a large part of the African continent is likely to see growth well short of that needed to significantly raise living standards, and reduce unemployment and poverty.