South Africa’s Economic Slowdown and Its Policy Options

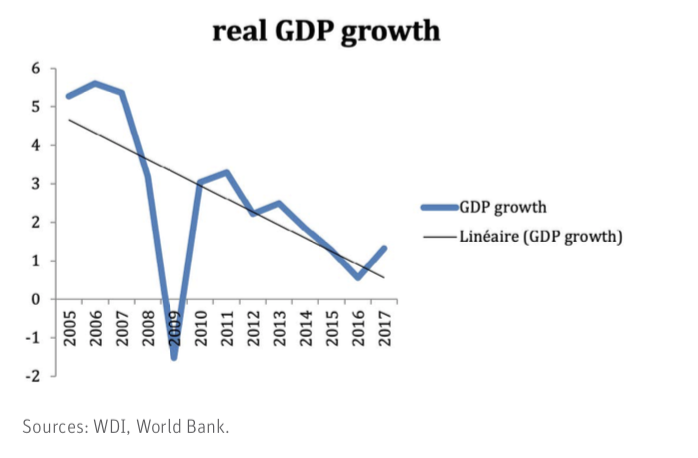

South Africa has not been exempted from the recent economic turmoil affecting several emerging countries. As the first second-largest economy on the continent, South Africa is going through an economic downturn since 2014 with a continuous fall in GDP per capital. Additionally, real GDP growth has experienced serious volatility and a decreasing trend since 2010 after briefly recovering from the 2008 global crisis. Indeed, between 2010 and 2016, GDP growth fell from 3,03% fell to 0,56% (Figure 1). In the meantime, the external sector did not perform better; despite a continuous nominal depreciation of the Rand, exports strongly receded between 2013 and 2017 passing from 3,98% to -0,097%. The timid recovery in terms of the current account balance is mainly due to the mechanics of lower imports during that period (Figure 2).

Figure 1: South Africa Real GDP Growth

Figure 2: Inflation and External Sector

.png)

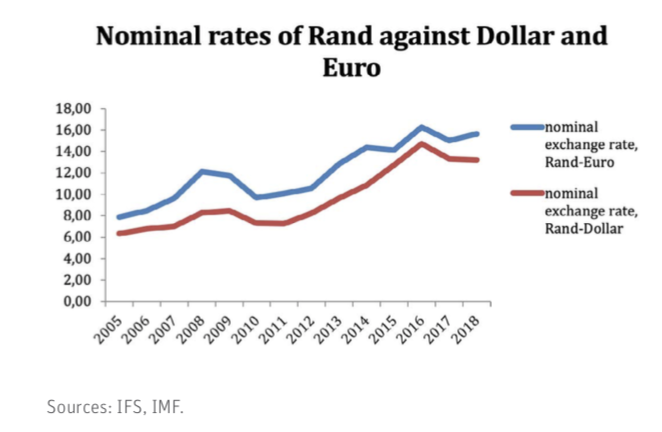

Inflation has remained relatively stable between 2013 and 2019, except for 2016 where the country experienced a little surge heading at 6,72% (against 5,28% and 4,71% in 2015 and 2017 respectively), but this change in inflation did not have a significant impact on the real effective exchange rate. This stance underlines two facts: the real depreciation is not due to lower prices in the economy but mainly to the nominal depreciation of the Rand (Figure 3).

Figure 3: nominal depreciation of the Rand against some world major currencies (indirect quote)

Second, the real depreciation (theoretically meaning that the economy is being more competitive) did not stimulate exports. Therefore one might reasonably think that the issue is in the production capabilities of the country that leads to a sluggish external sector despite some real depreciation.

Figure 4: Real effective exchange rate

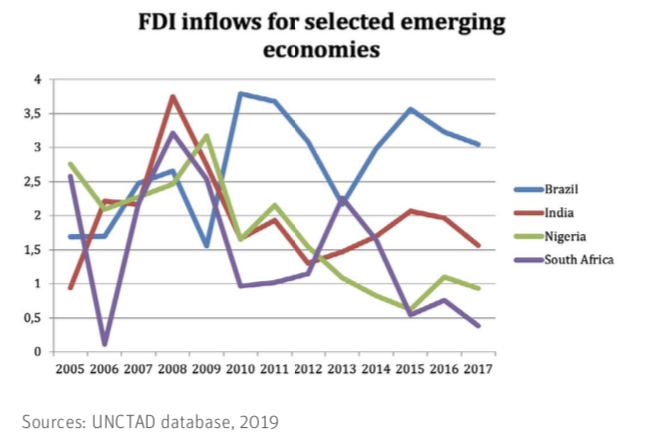

The reasons behind this period of weak economic performance are multiple and diverse. The 2008 financial crisis and the policy responses in both advanced and emerging economies played an important role, especially the implementation of the quantitative/qualitative easing and its tapering/unwinding that started in late 2013 and early 2014 for some countries. These policies have created huge inflows in FDI, and a few years later, important capital outflows from emerging economies. This situation has been particularly severe for South Africa as FDI declined by 74% in 2015 (the South African Institute of Race Relation). As figure 5 shows, a decrease in inflows of FDI has been more important for the South African economy compare to other emerging markets including Nigeria.

Figure 5: Flows of FDI in South Africa Compared to Selected Emerging Economies

As previously stated, the backlash from quantitative easing policy and its dollar carry trade consequence, have clearly played an important role, but some other structural determinants should be mentioned here. For some analysts, the South African economy suffers from the so-called middle-income trap. As suggested by Otsuka & al. (2017), the middle-income trap can be defined as “a growth slowdown of a middle-income economy that is aggravated by the inadequate responses to convergence forces, such as diminishing returns to capital and diminishing pool of copiable technologies”. In his comments, Mendez-Parra (2016) cites five reasons why middle-income countries like South Africa become stuck, the first one being the lack of key reforms in the manufacturing sector due to powerful interest groups (unions, workers etc.). This consequently prevents the economic transformation to persist (for example, unions fight to maintain labour intensive activities sometimes without any economic rationale). Second, without a reliable and internationally competitive manufacturing sector, pursuing economic transformation can be costly for the country (indeed if it is obliged to import all necessary inputs to its industry). After that, Mendez- Parra (2016) also cites the absence of policies favoring research and innovation and the lack of reforms to lock- in the positive aspects of international agreements. Last but not least is the political and institutional (e.g. corruption) framework not always favourable for an upgrade from a middle to a higher income economy. For South Africa, the political and institutional dimensions have certainly played an important role in the economic situation, indeed just after Mr. Cyril Ramaphosa took office as president of the Rainbow Nation, capital inflow significantly resumed (Figure 6), which is a possible sign of a regained confidence in the South African economy.

Figure 6: The “Magical” Effect of Ramaphosa’s Election

The direct consequence of such an economic situation is first on the social sectors, especially on employment. Unemployment remains important with a rate of around 27% and is more significant among youth as 53,4% remain without a job (ILO, 2018 country profile statistics). According to the South African Institute of Race Relation, the country needs at least a 5 to 6% growth rate for twenty years to reduce unemployment to about 10%. This social situation puts an important pressure on public finance as the South African Department of Social Development provides a monthly safety net to 17 million people. In a context of rising concerns on public finance, the 11 billion dollars spent to keep a third of the population out of poverty, questions remain unanswered on the real fiscal space available for the government (see infra).

What can be done?

There are two sets of solutions imaginable: structural or more mid/long term, and countercyclical measures.

The African Continental Free Trade Area: an unexpected opportunity

After a bit of hesitation, the South African government finally signed the CFTA agreement later in 2018. The CFTA will place Africa as the first common market in the world with more than (theoretically) 1.2 billion consumers covering 55 countries. According to the Economic Commission for Africa, the CFTA has the potential to boost intra-African trade by 52.3% (as import duties would be eliminated) and, these figures could be doubled in the case of the establishment of the continental customs union. There is no doubt that the continent will benefit from the effectiveness of the CFTA project, especially the most industrialized economies such as South Africa.

To take advantage of the CFTA, South Africa will need to (re) build its economy from consumption led to exports led growth. The issue here is not to judge negatively the social policy (especially the safety nets transfers to most vulnerable people), what is said is that other structural reforms are necessary. In other words, solutions to end poverty have sometimes to be seen sometimes through a “macroeconomic perspective”. One main challenge will be the job market and the issue of wages to be sorted out. Between 2017 and 2018, the country moved from the 62nd (over 135) to the 67th (over 140)

rank in the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI). The GCI has attributed this slight underperformance to the lower scores in macroeconomic stability, infrastructure, business dynamism, and financial system components of the GCI, to name a few. But as underlined by Gelb & al. (2017) one limit of the CGI ranking is that it can be disconnected from a country’s performance in terms of GDP per capita. For instance, South Africa ranks far higher on the GCI than in terms of GDP per capita. Higher formal wage levels coexist with 27% of unemployment (Gelb & al. 2017). Gelb & al. 2017 found that compared to other middle-income countries in their sample, South Africa’s labor costs are the highest. The relatively high wages in the South African manufacturing sector find their origin in the fight led by the National Bargaining Council for the Clothing Manufacturing Industry (NBC) with several other unions (e.g. the South African Clothing and Textile Workers Union -Sactwu) to impose higher wage to employers (Nattrass & Seekings 2013). It has been the case for employers in Newcastle, Northern KwaZulu-Natal area where “under the guise of promoting ‘decent work’ and the supposed levelling of the playing field for producers, an unholy coalition of a trade union, some employers and the state can initiate and drive a process of structural adjustment that undermines labour- intensive employment and exports South African jobs to lower-wage countries such as Lesotho and China”. Therefore, and despite the comparative advantage South Africa has in terms of manufacturing and agriculture on the continent, South Africa should resolve the issue of uncompetitive wage before being able to take advantage of the CFTA.

In the same vein, the current situation of Eskom and the severe electricity cuts have a significant impact on business development in the country. The financial situation of Eskom raises serious concerns on both economic activity and public finances. The South African government has recently announced a bailout plan of $ 4.8 billion over three years, but this plan may not be enough to overcome the electricity issue since more than $10 billion are necessary over a decade to overcome the Eskom’s financial turmoil.

A competitive South African manufacturing sector will definitely require deep and courageous structural reforms that will need to be accompanied by active short term and other cyclical measures. What can be done on the fiscal and monetary side?

The Fiscal Policy: Not Much Space Left

At first sight, the fiscal figures do not seem that worrisome. The overall fiscal deficit reached 4.6% in 2018 and is forecasted at 4.5% for 2019. In comparison, during the 2010-2015 period, the fiscal balance was positive and represented 0.1% of GDP. Also, debt levels represented 55.7% and 57.3% for 2018 and forecast for 2019 respectively1 which is not that high. However, what complicates the situation is weak growth prospects with a forecast of real GDP at 1.4% in 2019. Even more so than the traditional debt sustainability and fiscal solvency analysis, the perception of the fiscal situation by investors and government creditors plays an important role. Therefore, is there enough space for the South African government to run a more expansive fiscal policy to support economic activity?

Answering this question will lead us to see the rate awarded to the country by dedicated agencies. These ratings that have a great influence on the countries spreads. Even prior to the forthcoming release of the South African debt rates (later in March early April 2019), Moody’s agency, despite maintaining the “Baa3” grade for the country, negatively commented on the government’s budget speech. The government announcement of larger support to (bailout) Eskom without any significant improvement in the fiscal revenue side is creating more debt in a low growth environment. The whole thing is weakening a bit more the fiscal stability and flexibility. It is likely then that Moody’s will downgrade South Africa’s bills to “junk status” with probably a negative outlook. The fiscal instrument looks constrained in such a gloomy context, as public authorities have the delicate mission to keep investors and other agents’ anticipations on the South African economy as positive as possible.

What Role for the South African Reserve Bank?

If this question was asked before 2008, the answer would be clear and quite simple: Central bank should only focus on inflation stabilization objective. Indeed the “new classical economists” keep monetary policy at a minimum role possible since the inflation rate is believed to automatically adjust to anticipated levels of the monetary base. But the unconventional monetary policies in major economies such as the Bank of Japan (BoJ), the United States Federal Reserve (FED) and later the European Central Bank (ECB) have broken the taboo on active monetary policy imposed by the so-called Washington Consensus. Both quantitative and qualitative easing helped the US and the world economy in a sense to overcome the financial crisis in the aftermath of 2008. Therefore one can wonder if the South African Reserve Bank can use quantitative easing to support activity and rescue fiscal policy?

Theoretically, a scenario whereby the South African Central Bank buys treasury or private bonds is imaginable, but before addressing this point, an understanding of the country’s monetary policy framework is essential.

The South African Inflation Targeting Policy

Since February 2000, South Africa’s monetary policy has been based on an inflation targeting strategy, the monetary policy’s main objective is to keep consumer price index between a target band of 3 and 6%. Such policy combines flexibility as the band is quite large and facilitates progressive adjustment. Second, an inflation-targeting framework gives the opportunity to easily assess the Central Bank’s effectiveness in reaching the assigned objective. Also for a developing country, a nominal anchor helps agents to form their inflation and activity levels expectations. After almost two decades of inflation targeting framework, no doubt that inflation expectations are more deeply anchored than before (Miyajima & Yetman 2018). However, as found by Miyajima & Yetman (2018), agents involved in the wage and price negotiation have inflation expectations anchored well above the upper bound of the target2.

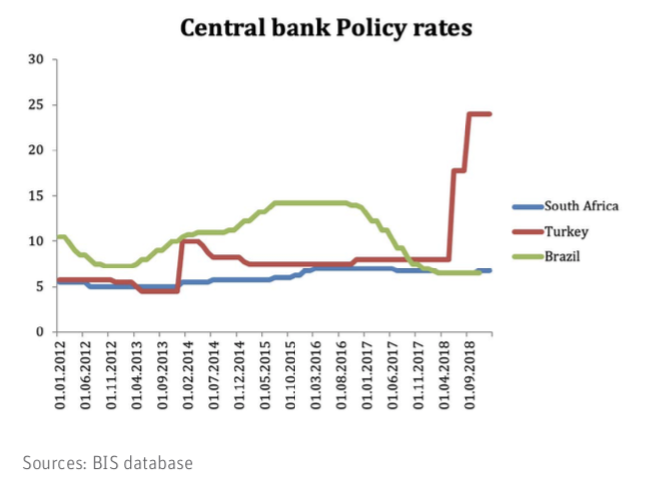

If one considers the Central bank’s policy rate in the last two years, it is noticeable that there did not have much movement on that aggregate. Prior to 2017, the policy rate slightly increased despite the morose economic stance, probably reflecting the Central Bank’s willingness to keep the inflation rate inside targeted bands (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Central bank policy rate

Relevance for quantitative/qualitative easing

In such a context, what can be done in terms of monetary policy? For example, would it be possible for the Central bank to rescue Eskom?

My answer is that use of seigneuriage for fiscal purposes is achievable under certain conditions (see infra), but thanks to inflation, South Africa does not need to resort to such heterodox policies to overcome sluggish levels of activity. The positive rate of inflation makes monetary policy still effective without any need to use the “planche à billets” (i.e. South African economy is far away from the liquidity trap zone).

Therefore active monetary policy can consist in significantly lowering policy rate to allow commercial banks to provide enough liquidity to the economy and thus stimulate activity and investment. However, two risks are associated with such a strategy: conflict with the inflation target objective and constraint to keep international reserves at decent level3.

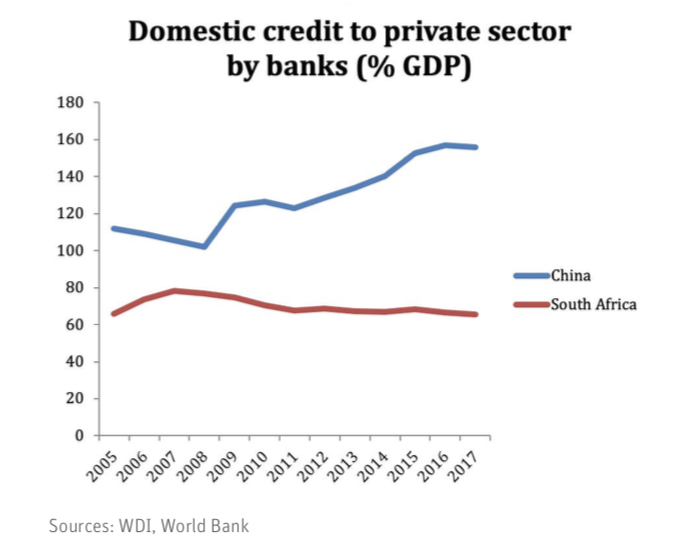

Indeed a clear mandate has been given to the South African Reserve Bank to maintain inflation rate inside targeted bands, but the economic stagnation gives the opportunity to reconsider the monetary policy framework. This rule could be relaxed for a period while allowing the Central bank to lower policy rates and stimulate domestic credit. The current figures shows (e.g. relatively to China) that for South Africa domestic credit by banks can be increased, and this could be targeted to dynamic exporting manufactures or SMEs for reducing unemployment rates (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Domestic credit provided by the banking sector

Concluding remarks

The South African Reserve Bank monetary policy committee has recently, against all odds, increased its benchmark interest rate from 6.5% to 6.75% despite the country’s economic situation. The governor of the Central bank justified this decision by the fact that “challenges to economic growth are more structural”, which means that monetary policy alone is not enough to alleviate the constraints against higher economic activity. There is no doubt that structural reforms are necessary especially in the labor market where inflation expectations are often disconnected from the nominal anchor provided by the inflation targeting policy. But the situation South Africa faces is quite challenging: fiscal policy constrained and threatened by a possible downgraded position by rating agencies. Additionally, the high unemployment rates, especially for youth, while growth prospects remain shy, is problematic. Therefore short-term policy actions are highly advised, even if unconventional monetary policy is not on the agenda, as the latter could target a bit more directly the economic activity stance. Given the high level of resources underutilization, recall the rate of 27% of unemployment; inflation can be reasonably seen as a minor threat. A credit selection policy or the implementation of a dedicated bank to SMEs/exporting manufacturers (fully or partially supported by the Central bank) is an example worth considering.

One thing is certain, inflation-targeting has appeared in recent years as not sufficient to secure a high and sustained level of growth. Blanchard & al. (2013) has provided an extensive discussion on that...