A Straitjacket to Help Brazil Fight Fiscal Obesity

Brazil’s GDP contraction since mid-2014 has multiple non-fiscal roots - Canuto (2016a; 2014) – but it has morphed into an unsustainable fiscal trajectory (Canuto, 2016b). Dealing with the latter has become a precondition for full economic recovery and the Brazilian government has submitted to Congress a constitutional amendment bill mandating a public spending cap for the next 20 years. This piece considers how the Brazilian landscape evolved toward such a precipice and why additional reforms – particularly on pensions - will have to be implemented to make the spending cap feasible.

Toward fiscal obesity

As we discussed in our previous piece, Brazil has featured anemic productivity increases in the last decades (Canuto, 2016c). And those have taken place while a political desire to finally come to terms with the poverty and inequality, which remained unabated during previous decades of rising per-capita income levels, has also been exercised. Such a political desire, after the return to democracy, translated into a large and increasing role for the public sector; consider that primary government expenditures as a proportion of GDP rose from 22% in 1991 to 36% in 2014. The uptick of public spending took place with increased earmarking of tax revenues and the ability of interest groups to maintain existing privileges. It was matched by a rising tax burden based on levies on consumption and also dependent on rising levels of formalization in the labor market. When the conditions that allowed for the growth-cum-poverty-reduction experience of 2003-2010 exhausted, the aftereffects of the fiscal pro-activeness on the economy became hard to trim. Had productivity risen more than it did, the demand on government services in absolute terms would have meant less of a share of GDP and of a tax burden on the private sector. On the other hand, the run-up to a fiscal overweight condition was pushed forward and postponed as the boom of the new millennium unfolded. Indeed, even without substantial productivity gains, the Brazilian economy went through a period of macroeconomic stability and economic growth-cum-poverty-reduction in the first decade of new millennium (World Bank, 2016, chapter 1). The preservation of the “economic policy tripod” – inflation targeting, floating exchange rates and significant government primary surpluses – held through the transition from President Fernando Henrique Cardoso to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva led to substantial “stabilization gains” as gauged by rising business confidence and decreasing risk premiums, which culminated with the upgrade of public debt to an investment grade status by the three major international rating agencies.

Such stabilization gains in a context of very favorable external conditions – the upward phase of the super-cycle of commodities and the abundance of global liquidity – paved the way for a prolonged boom. The creation of formal jobs proceeded at a fast pace, with rising rates of formalization in the labor market and unemployment rates falling from 11% in the beginning of the decade to 5% in 2010. The differential income growth at the bottom of the social pyramid was particularly remarkable, with a correspondingly impressive emergence of a “new middle class”. While GDP grew at an average rate of 4.5% per year, income of the bottom 20% rose at rates above 7% p.a.

The favorable external scenario supported growth in several ways. Rising commodity prices provided a fiscal windfall, used to boost social objectives while leaving existing privileges unscathed. Improved terms of trade translated into increasing domestic purchasing power of goods and services, besides positive wealth effects for natural-resource owners. Foreign currency indebtedness of the private sector was facilitated. Official external reserves skyrocketed.

However, the upswing phase from 2004 onwards of the commodity super-cycle brought double-edge effects, while reinforcing the consumption-led, labor income-led underlying growth model. Combined with exchange rate appreciation and rising minimum wage floors – as well as public-sector disbursements indexed to the latter – the commodity boom allowed a virtuous domestic cycle featuring positive feedback loops between consumption – especially services - and formal employment. On the other hand, profitability levels in the manufacturing industry were crushed and levels of production practically stagnated after 2008 before ultimately declining in 2014. The Brazilian economy ran toward a “competitiveness cliff” (Canuto, Cavallari and Reis, 2013). With the fall of global prices of metals since 2012, followed by food prices in 2014, the cycle began to unfold in the opposite direction.

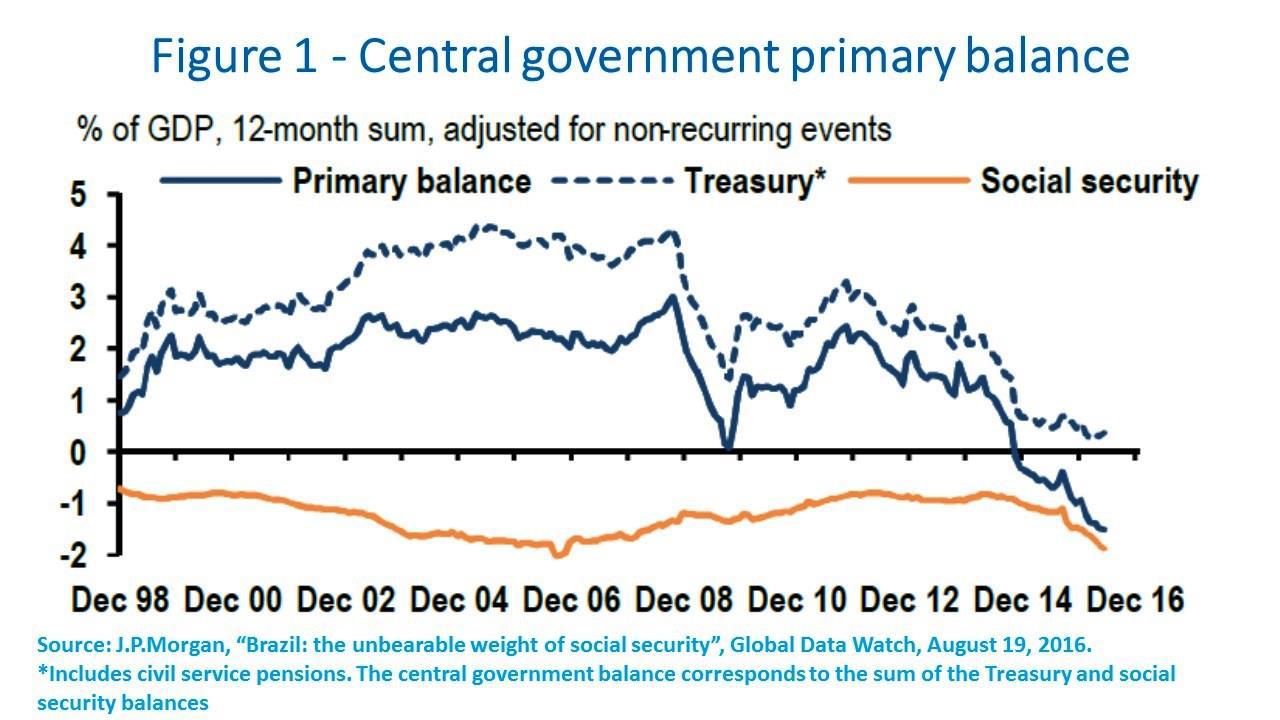

It is in that context that the government attempted to find a shortcut to a new, investment-led growth cycle in 2012-2014. In response to the global financial shocks in 2008-2009, the Brazilian government had employed counter-cyclical fiscal and monetary policies that helped lift GDP by more than 7% in 2010. As growth returned to lower levels afterwards, the government implemented a second round of stimulus policies, including a sizable package of tax exemptions, local-content policies, credit expansion via transfers of proceeds of public-debt issuance to public-sector banks and, in a failed attempt to slow down inflation without hiking interest rates, curbs on regulated prices. It is worth noticing that the expansion of public spending accelerated after 2008 and tax revenues have collapsed since the beginning of the economic downturn in mid-2014. Given the structural reasons for the private investment retrenchment, the main legacy of what we have called a failed effort to “chase animal spirits” (Canuto, 2013) was mainly fiscal deterioration – as depicted in Figure 1.

In fact, macroeconomic policies implemented in 2015 may be primarily seen as the unwinding of that attempted shortcut. The upward realignment of regulated (relative to free) prices, together with the realignment of foreign versus domestic prices (exchange rate depreciation), both led to an expected inflation shock. The Central Bank then used interest rate hikes to contain expectations of future inflation and avoid the diffusion of the corrective inflation shock. Furthermore, ambitious targets of fiscal adjustments were announced at the beginning of the year, although the barriers to reach such targets – rigid, legally-mandated public expenditure rises with pensions and others – came to be recognized with successive announcements of unwinding of fiscal targets.

Another factor behind the current bust has been the collapse of private investment following the investigations of market rigging and corruption initially associated with Petrobras, the state-controlled oil company, which subsequently spread to much of private-public sector interaction. Large and GDP-relevant domestic private groups involved in those scandals have faced direct impacts – financial drought, operational disarray, and a sudden halt on demand. Furthermore, deteriorating confidence has spread throughout, accompanied by a “wait-and-see” attitude pervasive with outsiders. The ensuing political crisis not only reinforced the investment paralysis, but also hindered the congressional approval of fiscal adjustment measures.

The medium-term silver lining of the investigations is an improved perception of rule-of-law by investors, besides a fiercer private-sector competition and a reduced cost-effectiveness of public spending in those activities where there is an interface between public and private sectors. However, in the short term, these non-economic factors have been partly responsible for the GDP decline. Furthermore, as tax revenues fell at an even faster rate than GDP, the fiscal adjustment effort has been thwarted and an open fiscal crisis came to the fore.

To summarize at this point, the combination of anemic productivity increases and a substantial growth in public expenditures oriented toward government transfers (pensions, social programs) – and real wages rising faster than productivity - during the growth-cum-poverty-reduction cycle was sustainable only while external conditions were highly favorable. Now, a medium-term fiscal adjustment – to be supported by measures to raise the pace of productivity increases - has become essential to return to inclusive growth.

The straitjacket on public spending

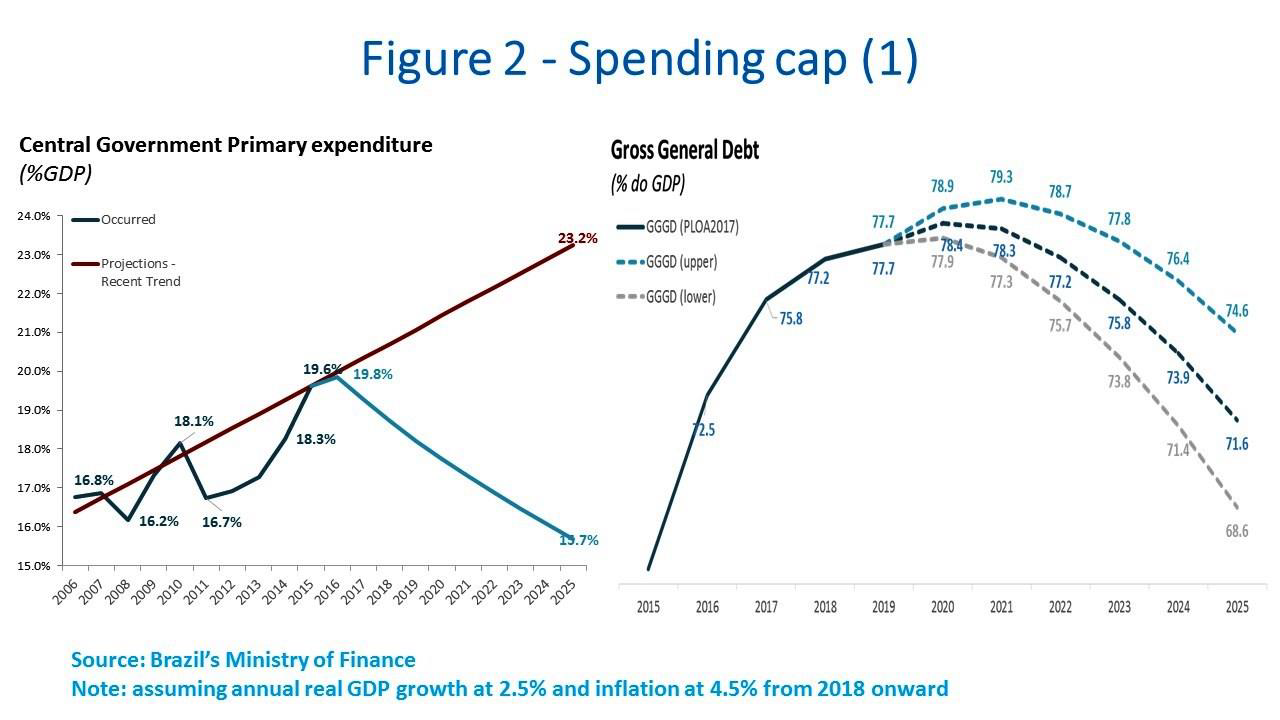

Reversing the explosive fiscal trajectory of the last few years has become widely accepted as a government policy top priority. The Brazilian government has proposed to Congress a constitutional amendment forbidding central government expenditures for up to 20 years to increase annually in nominal terms by more than the inflation rate of the previous year. Provided that the inflation stabilizes at some level, such a cap will eventually mean a decrease of public expenditures as a ratio of GDP as soon as the latter exhibits positive figures – even if public spending keeps rising in real terms in the immediate future ahead while inflation remains on a descending path. If tax revenues accompany GDP, the fiscal rule will automatically lead to reversal of negative primary balances and of the current rising trend of fiscal imbalance and public debt. The rule may be understood as a trade-off of medium-term enhancement of the fiscal landscape in exchange for some flexibility in the short term, given the prevailing budget hard rigidities. See current simulations from the Ministry of Finance in Figure 2 and those from J.P.Morgan in Figure 3.

On October 10, the spending cap bill passed its first round vote at the Lower House. The main content of the bill has been maintained, with the addition that the disbursement for health and education in 2007 will be the floor for spending on these sectors in following years. Furthermore, the text increased and hardened noncompliance penalties, while also introducing a ban to additional credit that could augment primary spending.

Of course, the main requisite for success will be a review of public spending rigidities and legally-mandated increases. Not by chance, the government has declared that it will also send Congress a proposal of pension reform, a key ingredient of the recent fiscal excess, as a way to make space for other essential public expenditures not to be dramatically curbed.

Government forecasts point to a social security deficit around 2.7% of GDP next year, larger than the overall government deficit. Although currently still a moderate deficit, pension expenditures are poised to accelerate given demographic trends and prevailing rules. Brazil’s Ministry of Finance forecasts social security spending to reach almost 10% of GDP in ten years under existing conditions, even with GDP growing by 2.5% p.a. from 2018 onward. Brazil, for instance, is one of the very few countries without a minimum retirement age.

Figure 4 - extracted from a study by C. Fernandez, V. Moreira and C. Souza, contained in J.P.Morgan’s Global Data Watch of August 9, 2016 - illustrates how relatively “generous” Brazil’s social security system is compared with most other countries:

“Brazil paid 6.4% of GDP in pensions in 2011, even though only 7% of the population was above 64 years of age (orange dot marked “2011” in Figure 4). By 2016, total expenditure rose to 8.4% of GDP while the proportion of the population over 64 grew to 8.2% (dot marked “2016” in Figure 4). Spending is far above the OECD trend, which suggests that Brazil spends as much as countries with higher proportions of people over 64, of about 13% in 2011 and 16% in 2016 (dots around the center of Figure 4). Pensions in Chile, a Latin American peer, amounted to 3.2% of GDP in 2011, with 9.9% of the population older than 64.” (Fernandez et al, “Brazil: The unbearable weight of social security”, J.P.Morgan, Global Data Watch, August 19, 2016).

The two previous fiscal adjustments in the last 20 years – at the end of the 1990s and after President Lula’s first election – relied mainly on a combination of tax hikes, discretionary spending cuts and growth in following years. This time the tax burden is already relatively high, recovery of growth will be gradual and the share of discretionary spending is only about 25% of the total. Reform of mandatory expenditures as imposed by the straitjacket will have to happen.

More generally, a review of public spending should help abiding to the new constitutional rule. To the extent that one may locate benefits and public subsidies that do not find justification in terms of poverty reduction or needs of the productive system, their elimination would make room for redirection of the corresponding resources.

A review of public spending may also bring a great potential contribution to TFP and economic growth, with effects spanning across two of the factors behind the productivity anemia – infrastructure and business environment. For an economy with a high tax burden and proportion of public spending in GDP such as Brazil, improvements in the quality of the latter have significant direct and indirect impacts. More generally, international experience has shown how transparency, evaluation of results, accountability, and competition in public procurement reduce corruption and improve the quality of public spending. There is also evidence that the quality of public services (education, health etc.) responds positively to the presence of incentives that reward good performance. Improvements in the quality of public spending would provide gains not only as a significant part of GDP, but also as part of the production inputs used by the private sector.

The window of opportunity open with the corruption scandals should be used to upgrade governance in the interface between public and private sectors, with the gains that we have mentioned before: improved rule of law and corporate governance, resulting in lower risk perceptions; improved competition and market discipline in key sectors, particularly those bidding for public projects; and cutting out wide-spread kickbacks would reduce both public overspending and the notorious Brazil cost (“Custo Brasil”) born by the private sector (Canuto, George and Fleischhaker, 2016). In addition to the fiscal regime change, the government has also obtained – or is seeking - congressional approval for other reforms with potential positive effects on investments and productivity. As of the moment, this text is written: Petrobras has been freed from the obligation to invest in all pre-salt fields; a reform of the regulatory agencies law has improved their governance and budget independence; prevalence of negotiation over labor legislation; and simplification of two taxes with heavy impact on Brazil’s cost of doing business. The government has also launched a first package of new infrastructure concessions.

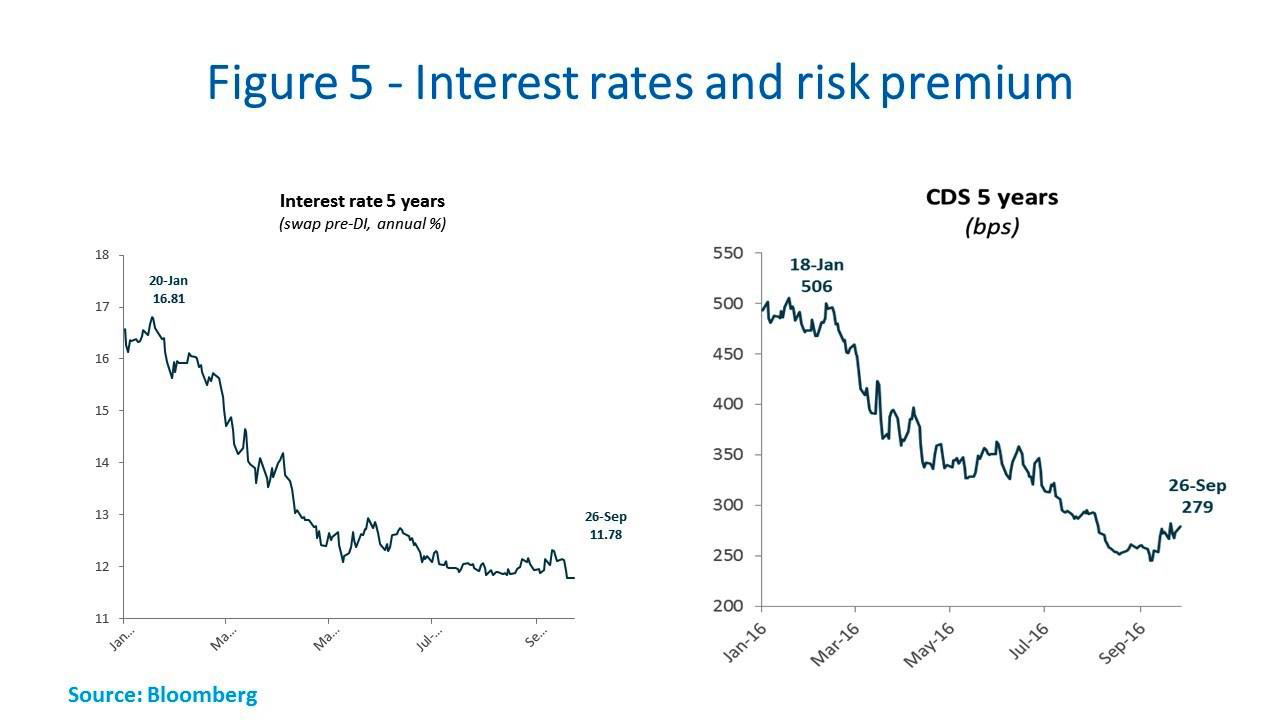

The economic agenda proposed by the government and the track record already established with respect to Congress’ approval have been among the factors explaining the favorable recent evolution of long-term interest rates and risk premiums levels (Figure 5). Confidence levels and other early signals point to a private investment-led recovery starting last quarter of this year.

Bottom line Besides fiscal adjustment, there is also now a widespread understanding that systematic increase in Brazil’s labor and total factor productivity will be requisite from now on for the growth-with-social-inclusion that prevailed in the 2000s to return. After all, only with productivity increase can the poverty reduction-motivated demand for government services be fully exercised without conflicting with fiscal soundness. Had Brazil performed better in terms of productivity, as well as with respect to socially unjustifiable fiscal privileges, it would probably not be having to cope with an overweight of public spending in its GDP.

Otaviano Canuto is the executive director at the board of the World Bank (WB) for Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Panama, Philippines, Suriname, and Trinidad & Tobago. The views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the WB or any of the governments he represents.