The Global Economy Remains Unbalanced

Discussions around large current account imbalances among systemically relevant economies as a threat to the stability of the global economy faded out in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. More recently, some signs of a possible resurgence of rising imbalances have brought back attention to the issue. We argue here that, while not a threat to global financial stability, the resurgence of these imbalances reveals a sub-par performance of the global economy in terms of foregone product and employment.

Are global imbalances rising again?

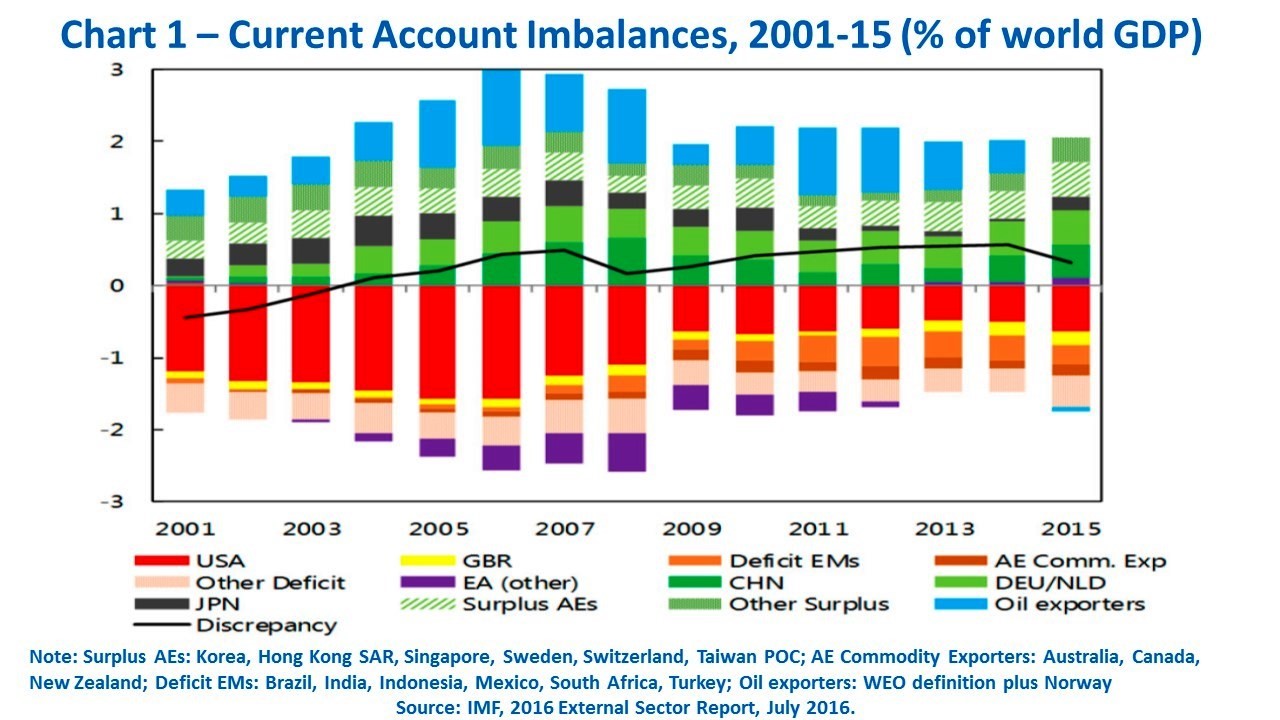

For five years now, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has produced an annual report on the evolution of global external imbalances – current account surpluses and deficits - and the external positions – stocks of foreign assets minus liabilities - of 29 systemically significant economies. Results for 2015 showed a moderate increase of global imbalances, after they had narrowed in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC) and stabilized in the interim (IMF, 2016) – see Chart 1.

The evolution of imbalances in 2015 depicted in Chart 1 is explained by the IMF as mostly reflecting three major drivers:

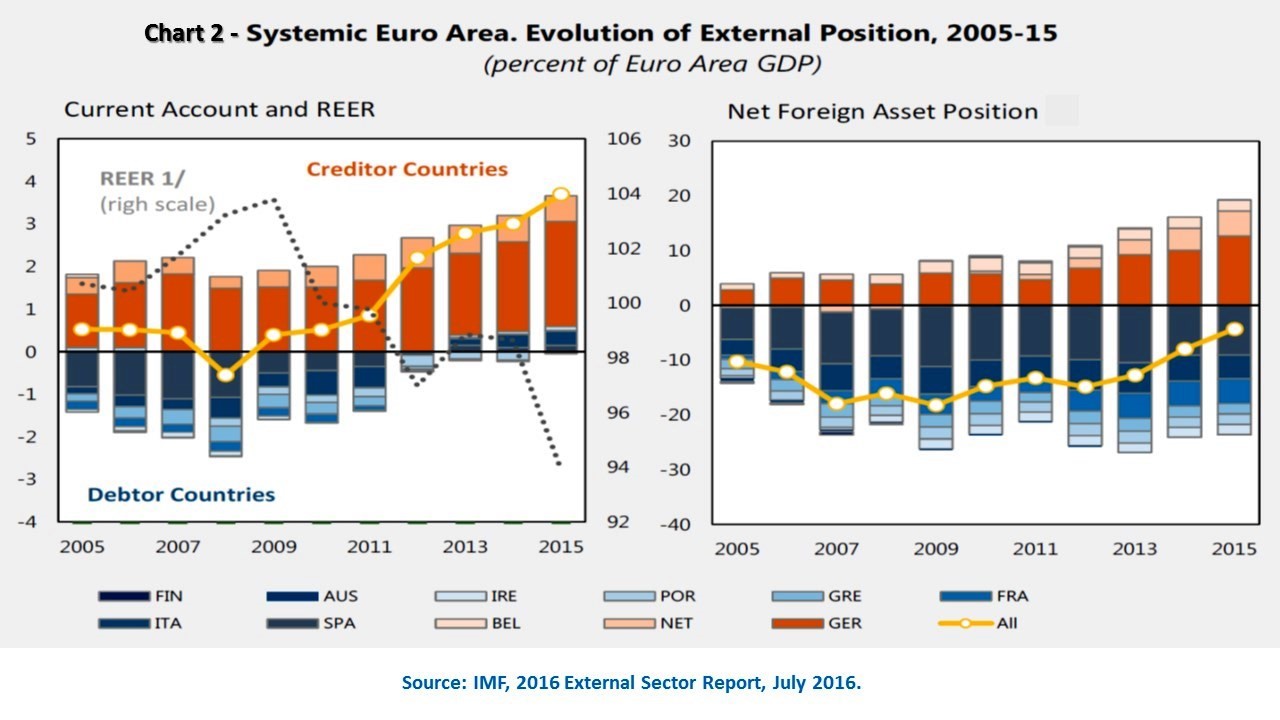

First, the recovery among advanced economies proceeded in an asymmetric fashion. Stronger recoveries in the U.S. and the U.K. relative to the euro area and Japan led to divergence in expected paths for monetary policies and appreciation of the dollar and sterling (pre-Brexit). The deficits of the U.S. and U.K. widened whereas surpluses increased in Japan and both debtor and creditor countries of the euro area (Chart 2).

Second, the fall of commodity prices – especially oil – transferred income from commodity exporters to importers. Overall however, it made only moderate contribution to narrowing imbalances.

Third, prospects of monetary policy normalization in the U.S., as well as bouts of fears about the softness of China’s rebalancing, contributed to a slowdown of capital inflows and depreciation pressures in emerging markets (Canuto, 2016a).

All in all, larger U.S. deficits and augmented surpluses in Japan, the Euro area and China more than compensated for smaller surpluses in oil exporters and smaller deficits in deficit emerging markets and Euro area debtor countries. Hence, global current account imbalances widened last year, even if “moderately”.

A picture of higher global imbalances, however, emerges if one focus on the rising surpluses of two systemically relevant groups of economies. Chart 2 exhibits how in the euro area deficits in debtor countries have shrunk in tandem with the maintenance of surpluses in creditor countries (slightly increasing in the case of Germany). While the net foreign asset position (liabilities) of debtors has not diminished as much, their current account adjustment has added to the soaring surpluses the euro area as a whole runs with the rest of the world. Setser (2016) in turn has called attention to how the six major East Asian surplus economies – China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan (China), Hong Kong (China), and Singapore – have reverted their post-GFC decline of surpluses and are currently topping even the euro area (Chart 3).

Such double trajectory of rising surpluses gives ground to those who have expressed concerns about a revival of rising current account imbalances as a source of risks to the global economy. While Eichengreen (2014) had declared “the era of global imbalances” to be over, more recently others believe they are “back” and claim that “rising global imbalances should be ringing alarm bells” (HSBC, according to Verma and Kawa (2016). To address this issue, however, it is worth first reviewing how the profile of current imbalances differs from the one prior to the GFC.

Global imbalances have evolved

The “era of global imbalances” up to the GFC (Chart 1) had two distinctive-yet-combined processes at its core:

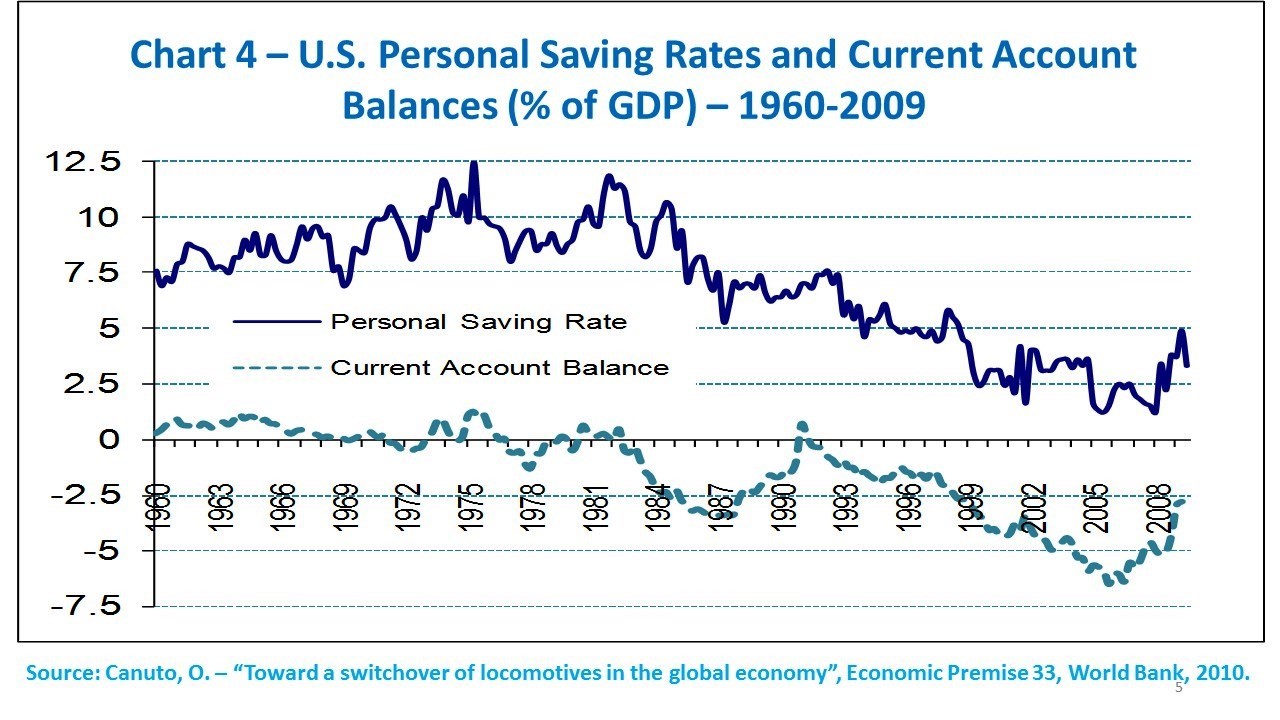

On the one hand, credit-driven, asset bubble-led growth in the U.S., along with wealth effects, intensified the existing trend of domestic absorption (particularly consumption) growing faster than GDP. This resulted in falling personal saving rates and increasing current account deficits (Chart 4) (Canuto, 2009; 2010).

On the other hand, the accelerated structural transformation and rapid growth in China, led to high and rising savings and investments and producing ever larger current account surpluses (Chart 5) (Canuto, 2013a).

Two caveats about these distinctive-yet-combined processes are needed. First, the bilateral U.S. deficit with China in the period shrinks by a third when measured in terms of value added, as China became a “hub or a stroke” of value chains with intermediate stages supplied from abroad (Canuto, 2013b). The U.S.-China bilateral imbalance therefore constituted outlets for production beyond China.

Second, while often linked as mirror images of each other – as in the hypothesis of an Asian “savings glut” causing low interest rates and asset price hikes in the U.S. (Bernanke, 2005) – the U.S. asset bubbles were more strongly associated to the “excess elasticity of the international monetary and financial system”, rather than to Asian current account surpluses (Borio and Disyatat,2011) (Borio, James, and Chin, 2014). Global current account imbalances cannot be blamed for the U.S.-originated GFC. As stressed by Eichengreen (2014):

“…the flows that mattered were not the net flows of capital from the rest of the world that financed America’s current-account deficit. Rather, they were the gross flows of finance from the US to Europe that allowed European banks to leverage their balance sheets, and the large, matching flows of money from European banks into toxic US subprime-linked securities.”

A parallel to that China-U.S. relationship can be traced within the euro area, including its later experience with a second dip of the GFC. The entry into effect of the euro as a common currency was followed by a risk premium convergence toward German levels and to cross-border banking flows at extremely easy conditions. Consequent asset bubbles creating wealth effects and excess domestic absorption – besides inflated financial intermediation - in southern Europe and Ireland led to the subsequent debt crisis. The pattern of intra-euro area current account imbalances exhibited in Chart 2 was primarily a consequence of euphoria taking place under conditions of “excess elasticity” of its financial system.

The commodity super-cycle also helped shape global imbalances in this period seen in Chart 1. However, it was to a large extent a consequence of extraordinary global growth prior to the crisis, one in which commodity-intensive emerging market economies maintained growth trends above those of advanced economies (Canuto, 2010).

While such a pattern of global imbalances was unfolding prior to the GFC, much discussion took place about its potential to spark a crisis on its own when faced with a sudden stop. China’s current account surpluses were boosted by depreciated levels of the exchange rate only sustained with a piling up of foreign reserves. The same evolution was interpreted by some as an expression of a savings glut unmatched by enough domestic availability of safe-and-liquid assets like U.S. Treasuries.

Regardless of the emphasis of causality one might establish between export-led strategies and saving-glut-cum-safe-asset-scarcity, analysts were split into two champs, as described by Eichengreen (2014). Some analysts feared a possible crisis of confidence in the dollar bringing capital flows to a sudden halt, while others saw imbalances as an exchange of cheap Asian goods for safe and liquid U.S. assets. In the latter case, imbalances might gradually unwind as export-led strategies reached exhaustion and/or the desire for asset accumulation approached satiation.

In any case, the GFC happened before that dispute was settled and global imbalances started to unwind in its aftermath. U.S. personal saving rates began to climb, borrowers reduced leverage, the dollar devalued and the U.S. current account deficit shrank from almost 6% of GDP in 2006 to much lower levels from 2009 onwards. At the same time, as shown in Chart 5, China initiated its rebalancing from an exports and investment-led growth model towards higher domestic consumption and services, including an appreciation of the RMB and lower growth rate targets. This has not meant a straightforward change of trajectory, as caution against a post-GFC hard landing favored continued high investment in domestic housing and infrastructure as a component of the transition (Canuto, 2013a).

As we already approached, deficits also diminished in the euro area in the aftermath of its debt crisis. The decline in commodity prices also helped global imbalances to shrink.

So, global imbalances did not spark a crisis and have returned in different configuration. Since current account balances are neither expected nor desired to be zero, how to make an assessment of whether the recent “moderate” uptick detected by the IMF might be a bad omen? Do those who have voiced concern over rising surpluses in East Asia and the euro area have a point? To answer these questions, it will be useful to look at the IMF exercise of judgement on whether global imbalances have been “in excess”, i.e. inconsistent with “fundamentals and desirable policies” (IMF, 2016, Box 1).

How misaligned with fundamentals have current account imbalances been?

National economies are not expected to exhibit zero current-account balances and stocks of net foreign assets. At any period of time, domestic absorption – consumption and investment – can be larger or smaller than the local GDP, triggering inflows or outflows of capital, due to “fundamental” factors:

- Differences in intertemporal preferences and age structures of their populations mean different ratios of domestic consumption to GDP;

- Differences in opportunities for investment also tend to lead to capital flows;

- Differences in institutional development levels, reserve currency statuses and other idiosyncratic features also generate capital flows and imbalances;

- Cyclical factors – including fluctuations in commodity prices – may also cause transitory increases and declines in balances; and

- Countries’ outstanding stocks of net foreign assets also have a counterpart in terms of service payments in their current accounts.

When global imbalances – and corresponding real effective exchange rates (REERs) - reflect such fundamentals, economies are in a better place than they would be in autarky (isolated with zero balances). There are situations, however, in which such imbalances may be gauged as in excess and countries should reduce them - as approached in Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti (2010; 2011).

There is the straightforward case of imbalances being magnified by domestic distortions, the removal of which would directly benefit the economy. For instance, this is the case when deficits are higher because of lax financial regulation fueling unsustainable credit booms or excessively loose fiscal policies. It is also the case of surpluses that reflect extremely high private savings due to lack of social insurance or investments being curbed because of a lack of efficient financial intermediation. It is worth noticing that, while excessive deficits eventually face a shortage of external finance, surpluses suffer less automatic pressures toward dissipation and can therefore persist for longer.

Furthermore, as pointed out by Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti, there are also situations in which the multilateral interdependence of economies calls for restricting current-account deficits or surpluses. Unsustainable deficits of large, financially integrated economies are such a case, as a crisis associated to them may trigger cross-border effects.

Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti additionally point out two conceivable situations in which surpluses can be deemed as in excess:

- When current-account surpluses are the result of deliberate strategies of curbing domestic demand and deliberate exchange rate undervaluation, crowding out foreign competitors. On the other hand, given the simultaneous determination of savings and current account balances, it is always hard to disentangle such a strategy from other determinants of the current-account balance.

- When an increase of one economy’s surplus takes place while others face difficulties to absorb it without suffering adverse, durable effects on their demand and output. This is the case when part of the world is caught in a “liquidity trap”, unable to resort to lowering domestic interest rates as an adjustment policy, or face obstacles to use countervailing fiscal policies.

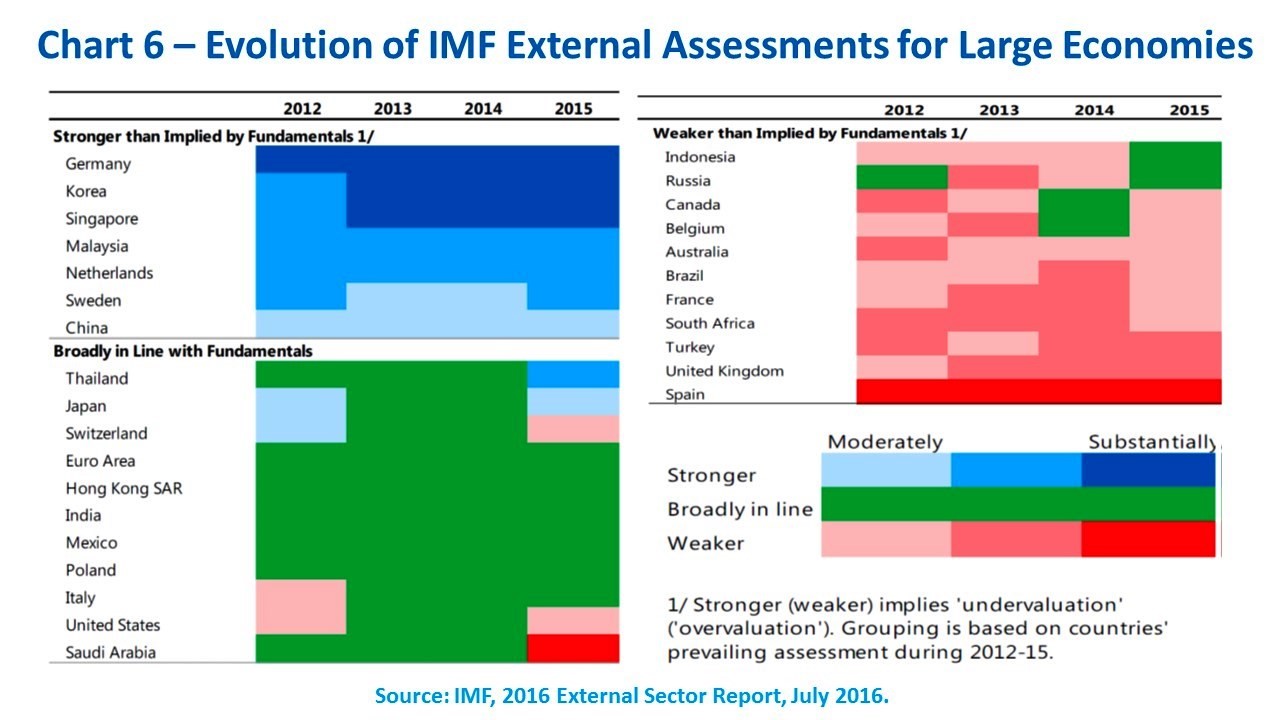

The IMF “External Sector Report” aims to gauge to what extent current account balances and corresponding REERs are out of line with “fundamentals and desirable policies”, as well as whether stocks of net foreign assets are evolving within sustainable boundaries. What did the latest issue show?

Chart 6 displays its assessments of how intensively individual economies have exhibited current accounts – and REERs – out of line with their “fundamentals”, i.e. those features that would normally lead them to feature current account imbalances within certain estimated country-specific ranges. Stronger (weaker) corresponds to REER “undervaluation” (“overvaluation”). Stronger (weaker) also means that a current account balance is actually larger (smaller) than that “consistent with fundamentals and desirable policies” (IMF, 2016, Box 1).

The report notices that the evolution toward less excess imbalances after the GFC has stopped and recent movements give motives for concern (IMF, 2016, p. 23):

First, those economies with external positions considered “substantially stronger” (Germany, Korea, Singapore) or “stronger” (Malaysia, Netherlands) have remained as such for the last 4 years. Also noticeable has been the shift toward stronger positions in the cases of Thailand and Japan.

Second, at the bottom of the distribution, while some countries reduced – or suppressed - degrees of “weakness” (Russia, Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, and France), others remained (Spain, Turkey, United Kingdom) – with the addition of Saudi Arabia to this group after the oil price decline.

Third, on-going trends of current account imbalances are bound to lead to a further widening of some external stock imbalances accumulated since the GFC. While China’s external stock position is expected to stabilize, other large economies are projected to exacerbate their debtor (U.S., UK) and creditor (Japan, Germany, Netherlands) positions. Furthermore, the net foreign asset position of some euro-crisis countries remain highly negative despite years of flow adjustment with high unemployment and low growth.

In our view, although not giving reason to fears of a collapse in major financial flows, global imbalances have not gone away as an issue, as they reveal that the global economic recovery may have been sub-par because of asymmetric excess surpluses in some countries and output below potential in many others. The end of the “era of global imbalances” may have been called too early. Lord Keynes’ argument about the asymmetry of adjustments between deficit and surplus economies remains stronger than ever.

Bottom line

The IMF report has a point in calling for a “recalibration” of macroeconomic policies from demand-diverting to demand-supportive measures. This will be particularly the case for countries currently able to resort to expansionary fiscal policies instead of relying mainly on monetary looseness – which has become increasingly ineffective at the margin. On the other hand, one must acknowledge that there are limits to extensive recalibration of national macroeconomic policies, as well as doubts about the extent to which national fiscal policies can deliver cross-border demand-pull effects. Huge savings flows – like German or U.S. corporate profits – may not be easy to redeploy.

Hence the priority to be given to country-specific structural reforms addressing obstacles to growth and rebalancing. Which could be aided by cross-border dislocation of pools of savings currently parked in low-return assets. Paradoxically, global imbalances demand more globalization in a moment in which the latter faces hurdles (Canuto, 2016b).

Otaviano Canuto is an Executive Director at the World Bank (WB). All opinions expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the institution or of those governments he represents at the WB Board.