China’s Spillovers on Latin America and the Caribbean

The Chinese economy is rebalancing while softening its growth pace. China’s spillovers on the global economy have operated through trade, commodity prices, and financial channels. The global reach of the effects from China’s transition have recently been illustrated in risk scenarios simulated for Latin American and the Caribbean economies.

The Chinese economy is rebalancing while softening its growth pace…

The weight of the Chinese economy in the global economy rose on its way to become the world’s second largest economy at market exchange rates and first in terms of purchasing power parity. As noted by the IMF (2016a, p.47), approximately one third of global growth during 2000-15 took place in China, while its exports increased from 3 percent to 9 percent as a share of world exports (Chart 1)

More recently, China’s economic growth has been morphing from one led by public investment and exports of manufactures, towards one where consumption and services are the main drivers (Canuto, 2013a) (IMF, 2016a). The new growth pattern entails lowering the GDP growth rates to levels that are more balanced and sustainable, based on rising purchasing power of its population and less dependent on huge trade deficits elsewhere in the global economy.

China’s transition, on the other hand, may face bumps. First of all, some complex, time-consuming structural reforms will need to be implemented. The provision of public services must be widened, in order to convince households to raise their propensity to consume. The business environment will have to be reconfigured as a necessary step to make possible moving up the sophistication ladder in value chains and overcoming so-called “middle income traps” (Agenor, Canuto and Jelenic, 2012) (Agenor, Canuto and Jelenic, 2014). The existing universe of state-owned enterprise will also need to be reformed.

Furthermore, there is the legacy of corporate debt and excess capacity in former lead sectors that resulted as a consequence of policies implemented to avoid a hard landing in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This legacy has been at the origin of occasional financial market jitters more recently. Fears of disorderly financial unraveling and abrupt exchange-rate depreciations have been behind episodes of capital outflows and loss of foreign reserves - Canuto and Gevorkyan (2016) - even if a more benign scenario has prevailed in recent months.

… leading to spillovers on the rest of the world…

In hindsight one now understands the core role played by China’s growth-cum-structural-change in the upswing and – in the last five years – downswing phases of the cycle during which developing and emerging market countries went from “switching over as global locomotives” - Canuto (2011) - to “getting lost in the transition” (Canuto, 2013b). Notwithstanding idiosyncratic, country-specific factors and policies underpinning the growth performance in those economies, they have all been impacted by the evolution of China’s economy – including the growth resilience exhibited by the latter after the global financial crisis, despite the cost of rising financial and capacity imbalances. The recent rebalancing of the Chinese economy has naturally also brought spillovers.

There are three channels through which those spillovers from China to the rest of the world have operated (IMF, 2016a, ch.2). First, there is trade as a direct channel. A faster-than-expected slowdown in imports and exports has reflected not only a deceleration in investment and manufacturing activities, but also a movement of densification of domestic value chains to the detriment of imports of intermediates or export-related inputs. China’s foreign trade was a key factor behind the world trade slowdown last year (Canuto, 2016).

Second, there are spillovers through commodity prices. The growth slowdown and rebalancing in the Chinese economy has been a major factor affecting the demand and prices of commodities. This is matched by developments on the supply side, following technological innovations and new capacities that emerged during the upswing phase of the super-cycle.

Third, there are the direct and indirect spillovers through financial channels. As bouts of uncertainty about the smoothness of China’s growth slowdown and policy changes often spark global risk aversion episodes, financial spillovers extend way beyond those economies that have developed deeper financial links with China. Interestingly, while the “taper tantrum” derived from U.S. monetary policy signals in the summer of 2013 - (Canuto, 2013c) – the turbulences in emerging markets’ exchange rates and capital flows in January 2014 could be traced to financial events in China (Canuto, 2014). This has also been the case in August 2015 and January this year.

… including Latin America and the Caribbean

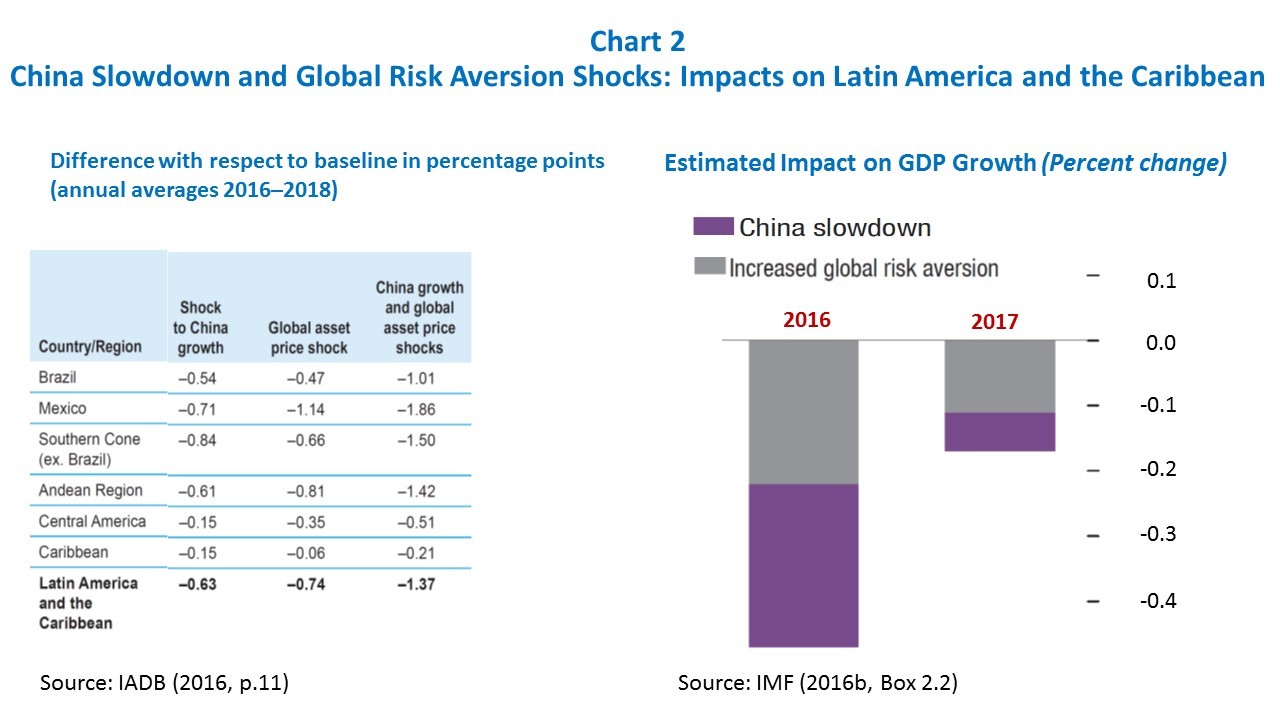

Spillovers from China, as it undergoes its growth-slowdown-cum-rebalancing are illustrated in recent simulations of the impact on Latin America and the Caribbean as reported last month by the International Monetary Fund - IMF (2016b) – and the Inter-American Development Bank - (IDB, 2016).

The IMF’s Regional Economic Outlook for the Western Hemisphere developed a risk scenario for Latin American and the Caribbean economies associated with a sudden bout of financial market turmoil in China. The simulation is based hypothetically on a wide set of the latter’s financial and real estate assets losing value, corporate risk premiums increasing, a new wave of capital outflows being triggered, the Renmimbi depreciating by about 15 percent, and falling investment and output. The supposed impact on the Chinese economy is a move of China’s growth 2 percentage points down relative to the IMF’s baseline in 2016 and 2017.

Such shock would affect the region not only through direct trade linkages, but also as a result of commodity prices being pulled downwards, with substantial declines in the case of minerals and fuels and smaller corrections in world food prices. As one would expect from the diversity of exposure to commodity prices in the region - Canuto (2015) - effects would tend to be highly heterogeneous notwithstanding their overall significance.

The IMF’s risk scenario also includes the effects of a rise in global risk aversion following the simulated financial turmoil in China, leading to a re-pricing of sovereign debt in the region. The overall results of both simulated stress factors are depicted on the right side of Chart 2:

“Based on model simulations, the cyclical slowdown in China could reduce growth in Latin America and the Caribbean by about ¼ percentage point in 2016 relative to the [IMF’s]World Economic Outlook baseline. In addition, an increase in sovereign risk premiums triggered by higher global risk aversion would cut growth by another ¼ percentage point. The overall impact declines in 2017 but is still negative (total of about 0.2 percentage point).” (IMF, 2016b, p.42)

The latest annual macroeconomic report of the Inter-American Development Bank also features risk scenarios for the region, that include the impact of a shock to China’s economic growth (of approximately 3 percent of GDP) and a global asset price shock (measured as a 10 percent fall in equity prices) - IDB (2016, p.9-10). The combined effect of both shocks would be something close to 1.4 percent per annum for 2015-2017 (Chart 2, left side). As illustrated in the IMF simulation, the impacts would be heterogeneous among countries but broadly significant.

China’s economic rise has also entailed increasing repercussions of its development in the rest of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean. No wonder there is so much attention and hope for smoothness in China’s current economic rebalancing. After all, what happens in China does not stay in China…

Otaviano Canuto is the executive director at the Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for Brazil, Cabo Verde, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guyana, Haiti, Nicaragua, Panama, Suriname, Timor Leste and Trinidad and Tobago. The views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the IMF or any of the governments he represents.

This article originally appeared in the Huffington Post