After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist

The situation in Mali continues to evolve and is making MINUSMA’s task further challenging. Civilians in northern and central Mali continue to suffer from protection issues. In fact, since June 2018, at least 287 civilians have been killed by extremist groups or have been victims of acts of atrocities from rival communities, the highest number recorded since the deployment of MINUSMA. MINUSMA earned its name of being the most dangerous UN mission in the world due to lack of sufficient equipment and training of contributing troops. Inequality between African and European peacekeepers has been identified as one factor contributing to its inability to prevent deadly attacks against its personnel and civilians. Finally, the Malian government and armed groups, signatories of the peace accord, have demonstrated a lack of leadership and unwillingness to find a common ground for significant progress of the peace process.

MINUSMA Base in Kidal, Northern Mali. Source: Author

Introduction

The 2012 Tuareg rebellion and coup d’état destabilized Mali, and violent extremist organizations (VEOs) exploited the security vacuum to occupy the north. This occupation and an attempt to expand further south, forced unexpected French intervention in January 2013 with support from the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA). In July 2013, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was created and replaced both AFISMA and the United Nations Office in Mali (UNOM).

On June 30th 2018, the Security Council extended the mandate of MINUSMA’s mission to June 30th, 2019. It has been almost six years since MINUSMA was established and the Malian conflict has proven to be challenging to manage. Mali remains destabilized and conflict has expanded from the north to central regions. This paper will address some of the challenges facing MINUSMA while it tries to fulfill its mandate. These concerns are mostly with regard to priorities highlighted in MINUSMA’s mandate, including protection of civilians and its personnel against asymmetric attacks, ability to provide support for the Malian government to restore its authority and its full territorial integrity, as well as to provide support for the implementation of the peace accord signed in June 2015. For the purpose of this paper, other topics are left to be discussed in a follow-up publication in the near future.

Protection of Civilians

Peacekeeping missions and international community attempts to protect civilians have not always been successful and this is true for MINUSMA. Despite MINUSMA’s presence in some areas where the Malian government is non-existent, the mission is struggling to provide sufficient protection to civilians, as indicated in its mandate. Since 2012, when armed conflict started, civilians felt abandoned when Malian authorities fled the north. Six years later, the feeling remains the same despite MINUSMA’s presence in limited areas. Civilians are lacking access to basic services but also remain unprotected and thus victims of insecurity. A refugee from Mopti Region stated:

“In addition to being unprotected, there are also no schools open, no health centers, no access to potable water, and no government services.” Livestock herder, Yidji village, Mopti Region.

The inception of the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali was meant to address the insufficient protection of civilians in collaboration with, and supporting Malian government and armed groups signatories of the Peace Accord. However, insecurity caused by violent extremist organizations (VEOs), armed groups, internal communal tensions, and armed banditry have complicated MINUSMA’s mission to prevent violence against civilians. This doesn’t mean MINUSMA is unwilling but rather is due to the complexity of local dynamics and the presence of multiple actors, which explains the further deterioration, and expansion of the conflict. Through its civilian-military activities, MINUSMA carried several quick-impact projects to assist civilians in most affected areas. Since 2013, MINUSMA completed at least 286 projects to provide and improve access to water, health, education, and food in northern and central Mali. The situation could have been even worse without MINUSMA’s efforts, especially in areas where the state remains absent. As one armed group leader stated:

“Because of its military and political presence, MINUSMA prevented leaving total void in areas where Malian government has yet to return. Civil servants, humanitarians, and non-government organizations workers are able to travel safely to troubled areas [north and center] only because of MINUSMA’s flights organized from the capital Bamako.”

MINUSMA patrolling the streets of Gao, Northern Mali. Source: Author

However, more than five years after the French and the UN intervention, civilians continue to experience serious human rights violations, to be displaced and intimidated by different actors. Armed groups and VEOs oppressed and abused civilian populations during the occupation of northern Mali in 2012. This trend has continued in the north by armed groups and expanded to central regions by the Malian forces committing similar acts. Civil servants, traditional, and religious leaders are relentlessly targeted and intimidated by VEOs while public services installations are being destroyed.

Tensions between local communities are worsening and civilians are being targeted as a result in northern and central Mali. In central Mali, Dogon and Fulani communities continue to engage in violence due to competition over access to natural resources. In the Ménaka Region, recent counterterrorism efforts led by ethnically based militias resulted in atrocities between Tuareg Daoussahaq and Fulani communities. With the absence of adequate protection and lack of permanent presence of Malian security forces, civilians have no choice but to rely on their own self-protection or on armed groups present in the area. However, most of the time these groups are either lacking resources, or protection of civilians doesn’t fall in line with their interests and priorities. Often these militias have unclear agendas and protection of civilians is used simply as a pretext to generate support and establish credibility within the national and international communities. For instance, at least two new militias emerged in May 2018 in Mopti and Ségou Regions following internal communal violence between Fulani and Dogon ethnic groups. Both militias justified their establishment on the basis of the lack of justice and protection of their respective communities. State absence and MINUSMA’s inability to protect those communities forced dozens of families to abandon their homes and find refuge in the suburbs of the capital Bamako with a potential for another humanitarian crisis. Refugees interviewed in Bamako expressed concerns for lack of protection and militias’ acts of atrocities against civilians as stated here:

“Malian government has done nothing and is incapable of doing anything to protect us from opposing armed militias. The solution is to quickly disarm all militias and promote national reconciliation.” Farmer from Diougani, Mopti Region.

Though the number of civilian casualties is difficult to confirm, one thing is certain, civilians are being targeted and killed by different actors under different circumstances and that is alarming. Recent United Nations Security Council report confirmed that 287 civilians killed in northern and central Mali between June and September 2018 alone, the highest number since MINUSMA was established. There are multiple reasons why civilians are targeted but in the case of Mali, there are two apparent ones: (1) hostile actors are ignoring the laws of war regarding the protection of civilians, and (2) have strong feelings of hate against opposing actors. In recent months, violence against civilians in Ménaka and Mopti Regions provide clear examples of this. This trend will most likely continue and the risk of atrocities against civilians remains high in both regions where the state remains absent and where the international community is struggling to fill that void along with armed groups who are signatories of the peace accord.

Insecurity

The widespread attacks and abuses on civilians by armed groups, militias, VEOs, and Malian security forces indicate that MINUSMA is currently inadequate when it comes to providing enough protection to civilians. In a territory almost the size of France, MINUSMA’s mandate is still challenging despite the increase of personnel to an estimated 15,209 uniformed personnel. Disparity between peacekeeping troops, weak Malian security forces, lack of adequate equipment and actionable intelligence, and involvement of militant groups have all contributed to MINUSMA being the most dangerous peacekeeping mission in the world.

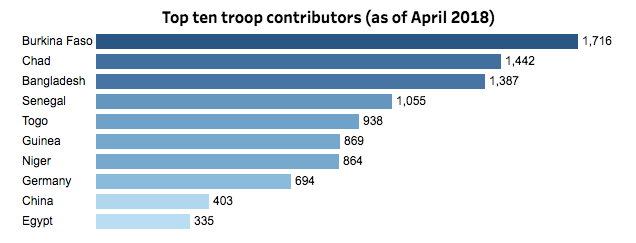

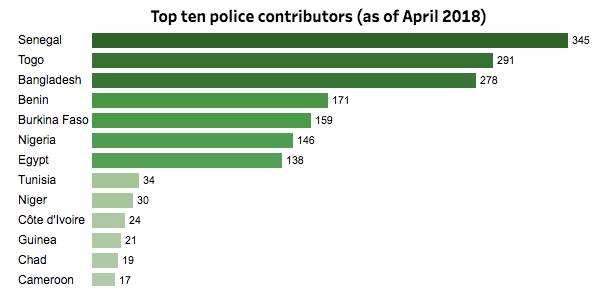

African countries dominate the top ten contributions of troops and police deployed within MINUSMA (Figure 1 and 2). Most contributing countries include neighbors like Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Senegal, Guinea, and Togo. Though further research is needed to better understand the reasoning behind this domination, one assumption could be troops from the region have a better understanding and are at some degree more familiar with the Malian conflict, culture, and local languages. Yet, this is not true since languages spoken in unstable parts of Mali are not necessarily the same in neighboring countries. Peacekeepers from neighboring countries do not necessarily speak Tamasheq [Tuareg language], Arabic, and Fulbe [Fulani language], and most spoken languages in northern and central Mali. For instance, if Burkinabe and Nigerien (from Niger) peacekeepers come from southern regions in their respective countries, the fact is that most likely also they don’t speak the languages [Arabic, Tamasheq, Fulbe, Songhai] that would be beneficial for their work. Furthermore, these countries might share borders but not necessarily share the same culture or understanding of the longstanding grievances toward the Malian government.

Figure 1: Data by International Peace Institute (IPI) of Contributing Troops in Mali

Figure 2: Data by International Peace Institute (IPI) of Contributing Troops in Mali

The most dangerous missions are carried out by African peacekeepers despite lacking adequate means. European peacekeepers are mostly based in MINUSMA’s headquarters in Bamako, Gao, or Timbuktu, the most relatively secured bases in the north since their mandates dictate where they can or can’t go, and under which conditions. Additionally, African troops are almost exclusively in charge of escorting logistical convoys in the most challenging geographical and security environments. While European peacekeepers possess more sophisticated equipment such as surveillance drones and air support, African troops do not benefit from those, and troops deployed rely on their own equipment. Research by the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) have demonstrated that a lack of trust and intelligence sharing, and inequality contribute to MINUSMA’s struggle. DIIS recommended, “minimizing the gap between the pledges of troop-contributing countries and the quality of the troops that they end up deploying,” and encouraged intelligence capability sharing to prevent further deadly attacks by extremist groups.

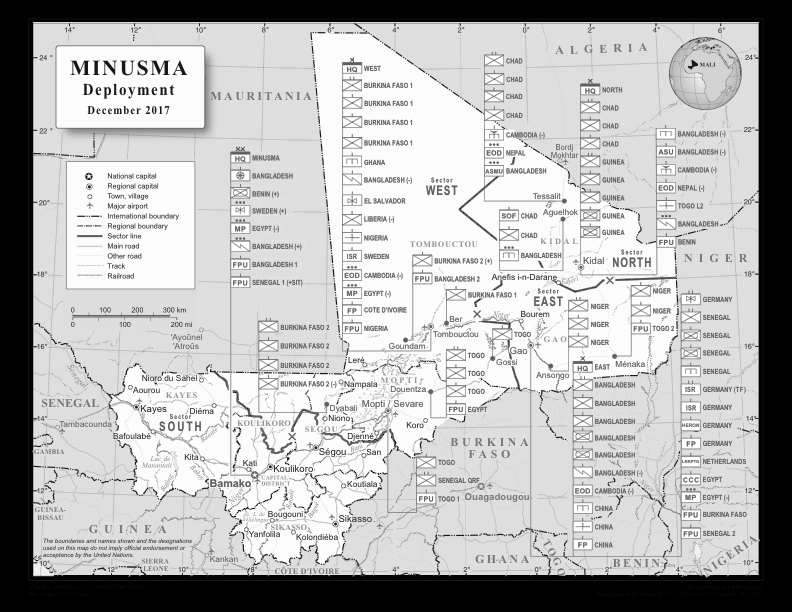

Chadian peacekeepers received high praise from the international community for their bravery fighting militant groups in Kidal Region in 2013. Simultaneously, they suffered the most in terms of casualties to this day--at least 47 died. The vital role Chadian troops played in defeating militant groups in one of their strongholds in Kidal Region was undeniable. This does not mean Chadian soldiers were well equipped nor well trained, but rather more willing to engage in areas where other troops were unwilling to go. They continue to be based (Map 1) in Aguelhoc, Tessalit, and Kidal--bases where their camps come frequently under rocket attacks and where their convoys are repeatedly targeted by improvised explosive devises.

Map 1: Distribution of MINUSMA Peacekeepers in Mali. Source: The United Nations Security Council.

Malian security forces and armed groups signatories of the peace accord are far from capable of providing protection to civilians as they claim. MINUSMA’s mandate required the protection of civilians and this has proven to be almost impossible in a volatile environment. Since its inception, MINUSMA camps and convoys have been constantly targeted by VEOs. As of October 16, 2018, at least 173 MINUSMA personnel have been killed and more than 360 wounded. In response, the mission has adjusted its operations towards a more defensive approach, rather than pro-actively engaging in protecting civilians at risk and without protection. The mission is exhausting its resources protecting its convoys and camps. As a result, trust and confidence of the population towards MINUSMA has started to decline and people perceive the forces as incapable of protecting them.

This feeling was intensified as MINUSMA found itself in crossfire between armed groups signatories of the peace accord not respecting the ceasefire agreement. Violence and tensions between these armed groups have led to acts of atrocities against civilians supporting one group or another and fingers again were pointed at MINUSMA for not doing enough to prevent such acts. Armed groups accused MINUSMA of siding with one group or another or more concerned by forcing the return of the Malian government to the north than stabilizing the area. On the other hand, the Malian government accused MINUSMA for not holding armed groups accountable when ceasefire was broken.

The situation in Mali has evolved since MINUSMA was created and so have militant groups. Under its initial mandate, MINUSMA was restricted from pro-actively engaging against VEOs. However, in June 2016 , MINUSMA became the only active peacekeeping mission from the other active 16 peacekeeping missions to have the task of countering asymmetric attacks in active defense. While it was encouraging for more offensive operations, this did not translate on the ground. Malian government and armed groups signatories to the peace accord continue to criticize MINUSMA’s weak mandate and restrictions to proactively go after terrorist groups. One Malian official told the author of the paper that the already overstretched and weakened Malian Army had to provide protection to MINUSMA’s convoys and thus labeled the mission as “useless.”

One challenge included in MINUSMA’s mandate is to assist the Malian central government in restoring its integrity and sovereignty throughout its national territories. However, the situation on the ground has proved to be more difficult than it initially appeared. Since extremist groups were chased from key centers of northern and central parts of the country in early 2013, state actors and security presence remained limited and absent in most areas from both regions [center and north]. In both regions, where Malian government and security forces are absent, they are losing further legitimacy as more civil servants and government officials fled the area due to insecurity or are unwilling to return. According to the UN Security Council report on Mali published in June 6th, 2018, only 33 percent of state officials were present at their duty stations in northern regions and Mopti region in the center of the country as of May 30, 2018. In the latest report of September 2018, 31 percent of state officials and civil servants were present in Mopti Region with temporary increase during presidential elections. Since 2013, a number of civil servants and government officials and employees have been assassinated or kidnapped, or received threats from militant groups for their collaboration with Malian government and with the international community, notably with MINUSMA and French forces.

Malian Army, gendarmerie, and police remain ill-equipped and too weak to face challenges posed by growing threats from extremist groups. Furthermore, documented acts of abuse against civilians and those suspected to be supporting militant groups raised concerns of MINSUMA’s readiness and legitimacy to protect Malian citizens already living in deteriorated humanitarian and security conditions. After the renewal of the mandate on June 30, 2018 MINUSMA should partly focus on improving legitimacy and perception of the Malian government and its security forces; two key factors for bringing stability in the north and the center of the country. This could be achieved by providing necessary support to Malian security forces in having positive contact with the population. Malian forces are conducting patrols in remote areas but do not have permanent presence, especially in the north and the center of the country. Simultaneously, however, Malian security forces should also be held accountable when acts of abuse are committed against civilians.

Implementation of the Peace Accord

MINUSMA is a mission with a peacekeeping mandate particularly focusing on supporting the peace process and reconciliations between Malian parties. It has been more than three years since the peace accord was signed but little has been achieved and progress has been moving at a slow pace. The Malian government and armed groups signatories of the peace accord don’t appear to be on the same page and have different priorities as recently reported by a workshop organized by the International Peace Institute (IPI) on May 8th, 2018. The Carter Center, in charge of overlooking the peace process, shared same concern in its first report released on May 28th, 2018. However, the follow-up report of August 2018 pointed out to positive progress as signatories of the accord demonstrated willingness to move forward with activities agreed on in January and March 2018, though the outcome remains to be seen.

With assistance from MINUSMA, the Malian government is prioritizing the return of its administration and security forces to the north with interest in restoring its territorial integrity. However, armed groups are focusing on issues related to governance such as decentralization, inclusivity of security institutions, and redistribution of national resources. Leadership of both parties struggling to agree on mutual interests and goals, and frustration of the affected population are increasing since they cannot see meaningful dividends of the peace accord.

MINUSMA is playing a major role in both: security-sector reform (SSR) and the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs. Overcoming the security threat relies on the success and fast results from both programs. The mission is aware that both SSR and DDR are long-term processes and will take decades to yield significant results. Simultaneously, MINUSMA should consider short-term goals so that Malian security forces, and eventually integrated former rebels,a are adequately equipped and trained to face insecurity challenges. Unfortunately, the Malian government and peace signatories have yet to reach an agreement about the number of former rebels to be integrated into Malian security forces. Both sides are unwilling to assume full responsibility of their roles in the Peace Accord process as one researcher close to the issue pointed out:

“There are several barriers to the peace process. The Carter Center has pinpointed several of the issues. But it mostly comes from the incapacity of the signatories to make the Accord their own. The Government, even it is identified as the "facilitator,” is not able to play that role. It is not able to provide a clear focal point, which makes it so that nobody is clearly responsible for the agreement. The armed groups are mostly concerned about their own privilege rather than finding a sustainable solution. And everybody profits from the standstill.”

Conclusion

On June 30, the current United Nations Security Council mandate of MINUSMA was renewed as expected. The situation on the ground continues to evolve and proves difficult to manage. Despite some progress, the implementation of the Peace Accord is moving at a very slow pace. The initiative by the Pace Agreement Monitoring Committee to create an independent observer of the peace process is a plausible start. Observations and recommendations by the independent observer should be taken seriously and is imperative to hold those hindering the process accountable.

The security situation further deteriorated and reached another level, notably in central parts of the country where more than 200 civilians have been killed since January 2018. Violent extremist groups capitalized on ongoing inter communal tensions in the center and the north. MINUSMA, its national and international partners, cannot afford further instability and divisions among different actors. The decline of violence in recent months between armed groups signatories of the Peace Accord are encouraging signs. MINUSMA should capitalize on this and encourage further collaboration for better protection to civilians.

Risks of further violence against civilians will remain high in the coming months especially without an adequate protection from national and international contributors. Asymmetric violence against MINUSMA and its personnel will persist, as VEOs will continue to attempt undermining genuine stabilization efforts by the mission. However, accelerating the re-integration of former rebels to the Malian security forces, Malian police training, and demonstrating increased presence through joint patrols in most instable areas to protect civilians are key to minimize the threat of further violence. Furthermore, increased state visibility will certainly re-establish some of its legitimacy along with armed group signatories of the Peace Accord by showing good faith and by engaging in the peace process.